How fitting that London and the British Prime Minister David Cameron should host the world anti-corruption summit on 12 May 2016. Presumably in the 1920s no one told Al Capone that he should hold a conference in Chicago on combatting organised crime. The Panama Papers confirm what we already know from a string of scandals: that the City of London is at the heart of the world’s biggest network of tax avoidance, money laundering and market rigging. These are the means by which capitalists retain their profits. Pension funds, insurance companies and stock markets are all beneficiaries. If the intention of publishing the Panama Papers was to embarrass the Russian and Chinese governments, British ruling class divisions over European Union membership, combined with resentment at banking profligacy and growing inequality in the midst of enforced austerity, quickly deflected attention on to Cameron himself. Trevor Rayne reports.

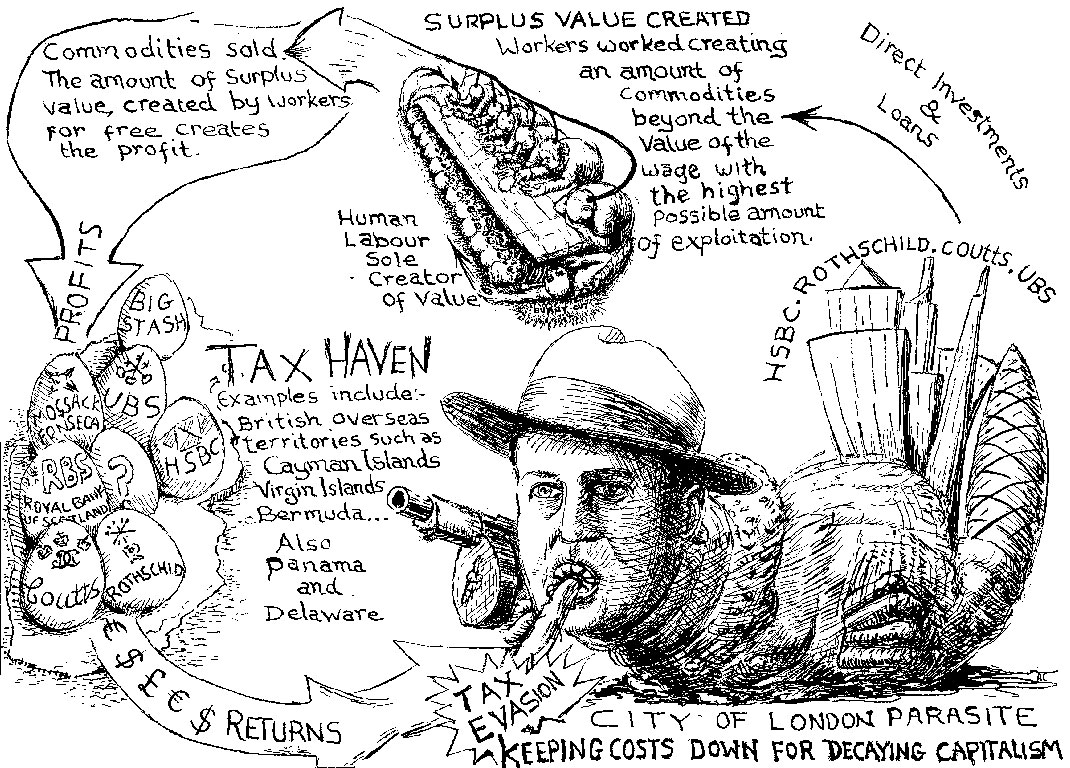

Profit increasingly takes a parasitic form: interest, currency exchange deals and the manipulation of financial assets. Fraud is an extension of these methods of securing a share of surplus value and is invaluable to the British ruling class. When Cameron proclaimed, ‘I’m determined that the UK must not become a safe haven for corrupt money from around the world,’ we knew it already is.

Eleven and a half million confidential documents from the Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca, providing information on 214,000 companies, were leaked to a German newspaper, Suddeutsche Zeitung. More than half the companies listed in these Panama Papers are registered in UK overseas territories or crown dependencies. Mossack Fonseca works with some of the world’s biggest banks to set up thousands of offshore companies, designed to avoid national tax and law enforcement authorities. Four of the ten banks that most frequently used Mossack Fonseca were British-based: HSBC, Coutts (the bank the Royal family use, owned by Royal Bank of Scotland), Rothschild and UBS. Mossack Fonseca provided legal entities, shell companies, frequently hiding their owners’ identities, and registered them in British controlled territories which have tax treaties with the City of London; particularly popular was the British Virgin Islands (BVI), some 950,000 businesses are incorporated there.

British overseas territories (BVI, Cayman Islands, Bermuda, Gibraltar and so on) and crown dependencies (Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man) offer what Nicholas Shaxson, author of Treasure Islands, about tax havens, calls the ‘theatre of probity’. Forced to respond, Cameron claimed that Britain’s offshore centres provide transparency ‘far in advance of most other countries…we ought to praise them and thank them for what they have done’. According to the Financial Times, Jersey held $1.7 trillion of deposits in 2013 and, together with Guernsey, generates about $100bn revenue a year for British banks. The weight of the City in the British economy is so great that no scandal will curb the government’s defence of its international position. The anti-corruption summit was intended to refurbish the ‘theatre of probity’, so appreciated by the assorted money launderers, insider dealers, tax evaders, banks and all those who prefer to operate in the shadows.

The Panama Papers were examined by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists before being released. This body is funded by the financier George Soros and the CIA-directed US Agency for International Development. The former British ambassador to Uzbekistan, Craig Murray, said: ‘Do not expect a genuine exposé of western capitalism. The dirty secrets of western corporations will remain unpublished. Expect hits at Russia, Iran and Syria and some tiny “balancing” western country like Iceland.’ The Guardian headlined the revelations: ‘The secret $2bn trail of deals that lead all the way to Putin’ (4 April 2016), following up with ‘China – how politburo’s “red nobility” set their sights far beyond politics’ (7 April 2016). No comment was made on the fact that China kept the legal and administrative machinery installed by Britain in Hong Kong for money laundering and tax avoidance when it took over in 1997. However, among the 12 national leaders, celebrities, footballers and the Brinks Mat gold bullion robbers named in the Papers, Ian Cameron, father of David, caught the eye.

The Times columnist Matthew Parris wrote, ‘This walks into every Eurosceptic’s dream… it is very, very dangerous.’ Sections of the media and supporters of the Conservative Party rounded on the Prime Minister: ‘Cameron’s tax dodge on mother’s £200,000 gift’ (Mail on Sunday); Cameron tried to ‘avoid inheritance tax of £80,000’ (The Sunday Telegraph). Cameron had to admit that he profited from an offshore trust set up by his father. For over 30 years Ian Cameron paid no taxes to Britain on his fund operated in the Bahamas, Blairmore Holdings, which hired local residents, including a part-time bishop, to sign off paperwork. Initially, David Cameron said the matter was ‘a private affair’, but the credibility of the ‘theatre of probity’ was imperilled and his tax affairs had to be disclosed. David Cameron sold his stake in Blairmore Holdings in January 2010. For a week Cameron lied about his business interests, before being forced to confess them.

Piles of cash

To think that offshore tax havens are the product of greedy individuals and crooks is mistaken; they serve them, but that is not their primary purpose. They derive from and flourish with the crisis of capitalist accumulation. In FRFI 245 David Yaffe wrote of US companies, that ‘some 64% of the more than $1.7 trillion cash is held abroad to avoid a tax bill on profits made in other countries’. Vast cash surpluses are building up that cannot find adequately profitable outlets for investment. Gabriel Zucman, assistant professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, estimates that $7.6 trillion is held in undeclared offshore funds. The British Tax Justice Network puts the figure at $24-36 trillion. Zucman reckons that in 2014 Britons held $284bn offshore, costing the government over £5bn a year in taxes (Nicholas Shaxson and Alex Cobham).

Eighty-three of the 100 largest US corporations and 99 of Europe’s 100 biggest companies use offshore subsidiaries. More than half the world’s trade in goods passes, on paper, through tax havens. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) reports that some 30% of cross-border corporate investment is routed through offshore ‘conduits’. ‘In 2012, the BVI was the fifth largest recipient of foreign direct investment globally, with inflows at $72bn, higher than those of the UK with an economy almost 3,000 times larger’ (Financial Times 8 April 2016). UNCTAD estimated $100bn of tax revenues were lost in 2015 because of tax havens.

Taxation is seen by the individual capitalist as a cost. If profits are sufficient, taxation can be paid, but if the rate of return is inadequate or profits decline, the burden of taxation becomes unbearable to the capitalist. Most state spending, for example on health and education, does not add to surplus value and is a deduction from the mass of profits. In so far as it is paid for out of taxation, or government borrowing resulting in future taxation, state spending becomes an unacceptable burden to the capitalists. The current stagnation in productivity growth exacerbates this problem. Giant corporate and individual cash piles, flourishing tax havens and the attacks on state spending are all manifestations of the capitalist crisis and its descent into parasitism and decay.

In the major capitalist countries the burden of taxation is being forced onto the working classes as taxes on companies are pushed down. In 1982 UK corporation tax on company profits was 52%. Today it is 20% and by 2020 Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne says it will be 17%. Ireland’s corporation tax is 12.5% and just 6.25% if firms show their earnings derive from research and development conducted in Ireland. Demands to reform tax havens, making them transparent, miss the point that this will only accelerate the reduction in corporation tax, which is the necessary reaction to declining global profitability.

The web is spun

The current global network of tax havens spun around the City (Shaxson likens it to a spider’s web with the City as the spider), derives from the 1950s when the British ruling class sought to maintain the City of London as a major international financial centre, while retreating from its colonial Empire. When Egypt’s Colonel Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal in 1956, British imperialists viewed this as threatening Britain’s position in the Middle East. Prime Minister Anthony Eden wanted Nasser assassinated. Together with Israel and France, Britain launched the Suez War to recapture the canal. The war led to a run on the pound and the US, seeing its opportunity, refused financial help until Britain agreed to withdraw its troops. After nine days, the British government announced a ceasefire. The Suez Crisis highlighted a conflict between upholding sterling as a world currency and funding the military operations required to maintain Britain’s world role.

To defend the pound, the government imposed restrictions on overseas lending by British banks. The banks, led by Midland Bank, responded by converting their lending to US dollars, so creating the Euro-dollar market with Bank of England complicity. As the trade was conducted in dollars British authorities saw no need to regulate or tax it and, as it took place in London, the US had no means of taxation or regulation. The Soviet Union already used the Euro-dollar market to deposit dollars beyond the reach of the US. US corporations and banks, avoiding US restrictions, followed into the market. Offshore tax havens were born. Sir George Bolton, formerly British executive director of the International Monetary Fund and in charge of Bank of England foreign exchange controls, explained: ‘By building an apparatus in an amazingly short time for the collection and redistribution of the world’s surplus cash and capital resources, the commercial banks have produced a unique machinery for serving the financial needs of the whole world, both East and West.’ Sir George’s Bank of London and South America specialised in lending from Euro-dollar deposits to Latin American governments. Mexico and Brazil took half the loans to underdeveloped countries.

The writer Anthony Sampson described Euro-dollars: ‘it was “money without a home”, which could flit across European frontiers to Caribbean islands, Singapore and Hong Kong’. The Euro-dollar market tripled in size in 1959 and doubled again in 1960. Foreign banks poured into the City, bankers’ salaries soared, new office blocks sprang up and office rents rose. The Cayman Islands took off as a banking centre in 1966, rivalling the Bahamas for tax exemption, taking in money from North and South America. In 1973, when it was revealed that the chair of the British mining multinational Lonrho, Lord Duncan-Sandys, received an extra £100,000 year tax free through the Cayman Islands, the then British Prime Minister Ted Heath called it the ‘unpleasant and unacceptable face of capitalism’. Unpleasant it was, but legal, presented in the British ‘theatre of probity’. By 1980 Grand Cayman registered 11,000 companies, more than its 10,000 inhabitants, and 80bn Euro-dollars in accounts. In 2015 the Cayman Islands had $2.6 trillion in liabilities, being the main offshore depository for British banks.

The US government response to the rise of the Euro-dollar market and offshore centres like the Cayman Islands was to loosen its own regulations and establish onshore tax havens. At the London anti-corruption summit this May, the Isle of Man’s chief minister called the US ‘a major secrecy jurisdiction and tax haven’. The Cayman Islands president said ten times more companies, 285,000, were registered in a single building in Delaware than on his islands. Cameron referred to the role of Delaware. In 2014, international disclosure rules were introduced to restrain tax havens, adopted almost everywhere, but not by the US. As one corporate lawyer put it, ‘I think the US is already the world’s largest offshore centre. It has done a real good job disabling competition from Swiss banks’ (Financial Times 9 May 2016). Capitalism in crisis and inter-imperialist rivalry cannot permit any restraints; cheating is necessary because sufficient profits cannot be made in the normal way.

David Yaffe, ‘Capitalism in crisis: stagnant, predatory and corrupt’, FRFI 245, June/July 2015.

Nicholas Shaxson and Alex Cobham, ‘The world’s hidden wealth’, Prospect, May 2016

Anthony Sampson, The Money Lenders, 1981

With thanks to Paul Bullock

Illustration by Andrew Cooper

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! 251 June/July 2016