Racist anti-migrant protests in the 26 Counties in the south of Ireland are on the rise. While food inflation soars above 12%, the housing crisis intensifies and poverty rises, the 26 Counties remains a haven for landlords and capital. The state is subsidising private landlords an estimated €1bn a year with housing support payments for people for whom there is no social housing (Rory Hearne, Gaffs, 2022). US tech and pharmaceutical multinational giants in particular profit from the south of Ireland having the second lowest corporate tax rate in Europe. The state infamously refused €13bn in unpaid taxes from Google in 2016. However, it is migrants, asylum seekers and refugees who some are blaming for their deteriorating standards of living.

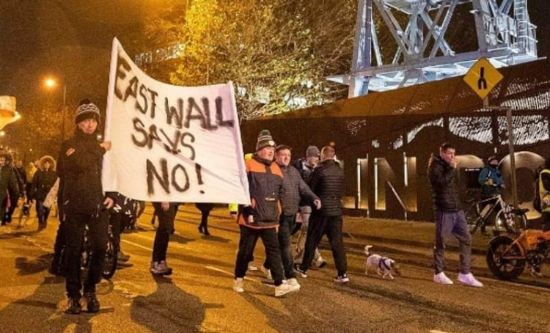

In November 2022 protests started in East Wall, Dublin, after a building was converted into emergency accommodation for asylum seekers without the prior knowledge of local residents. Since then hundreds of people have been marching in all major cities, under the banner of ‘Ireland for the Irish’, attacking the temporary accommodation housing asylum seekers and refugees, using racist lies and distortions to justify beating up migrants. Many of the protests have been organised by individuals who were involved in anti-lockdown and anti-vaccine protests.

In Dublin, one protest against housing asylum seekers and refugees started from rumours that a woman was sexually assaulted by a black person believed to be an asylum seeker. In fact Garda believed the perpetrator was a white Irish male. On 28 January 2023 homeless migrants in tents were attacked with baseball bats. Underlying this racism is a sharp increase in poverty – an extra 76,000 people became at risk of poverty in 2022 – and a housing crisis that has been looming for years.

Housing crisis

The banking lobby group Banking and Payments Federation Ireland found that between 2010 and 2022 average rents rose 82%, compared to an 18% average across the EU in the same period. Seven out of ten young people are considering emigrating due to the housing crisis.

42% of those in the private rented sector are families with children and one in five private renters have been energy insecure over the past year. One third of all people in private rentals are people in receipt of social housing subsidy and who should be living in social housing. Around two thirds of all social housing built since the Irish ‘Free State’ was established in 1922 is now privatised (Dara Turnbull, Financial Times, December 2022). Homelessness is at an all-time high, reaching an unprecedented 11,500 people in emergency shelters in January 2023 out of a population of five million – as well as untold numbers of rough-sleepers and couch surfers who were not included in official figures. In 2007 the state built 8,763 units of social housing, compared to 760 in 2013 and 2014.

Successive Fianna Fail, Fine Gael, Labour and Green coalition governments have failed to address the growing crisis, with schemes that are not even reaching their woefully inadequate targets. In 2018 the ‘Affordable Housing Fund’ promised 6,200 homes to rent or buy over a three-year-period. No affordable homes were delivered in 2019 or 2020. Eight were built in 2021.

Direct Provision

The south of Ireland state’s system of asylum seeker accommodation, Direct Provision centres, are largely converted buildings such as convents, mobile holiday homes and nursing homes. Set up as a short-term measure in 1999, people arriving in the 26 Counties seeking asylum were to live in these centres for up to six months while their applications were assessed. Today the average stay in Direct Provision is two years, with some residents having been there for over a decade. With the majority of centres contracted out by the state and run for-profit by private contractors, there are widespread accounts of the lack of nutritional food available, residents being denied food outside of set mealtimes and up to eight single adults forced to share a room. An adult’s weekly allowance is a mere €38.80. The majority have no right to access employment. 30% of those living in centres are children. In January 2023 it was reported 88 asylum seekers have been put up in 11 tents in sub-zero temperatures in County Clare. There are similar examples across the country.

The Irish Medical Journal in 2020 found half of asylum seekers in the south of Ireland had faced torture before their arrival. Escaping traumatic environments, when they arrive in the 26 Counties they are then forced into a vicious system that has been internationally criticised as degrading, cruel and inhumane.

In February 2021, the Irish state announced Direct Provision would end by 2024 and be replaced with a ‘blended’ accommodation system in which newly arrived asylum seekers would spend a maximum of four months in state-owned centres, before being moved into not-for-profit housing. In 2022 this plan was scrapped, blamed on the increase in refugees and asylum seekers. In 2020 there were approximately 9,000 refugees in the 26 Counties. By the end of 2022, this number was around 83,000, over 60,000 of them from Ukraine.

The 26 Counties automatically recognises Ukrainians as refugees, and they therefore skip the Direct Provision centres and the anguishing wait for asylum applications to be considered. The government provides Ukrainian refugees with work visas, English classes, accommodation largely in hotels, €208 a week, plus child benefits. The 26 Counties is aligned with the NATO bloc and has had a formal relationship with NATO since 1999. As such, Ukrainians are ‘good migrants’, not the ‘bad migrants’ from Asia, Latin America and Africa (see Nicki Jameson, FRFI 287, April/May 2022).

In reality the ‘blended’ accommodation system, which relied on enough adequate not-for-profit housing, was always a pipe dream.

There has often been domestic backlash against Direct Provision centres, particularly when the state tried to set them up in poor and working-class communities, without consultation or increasing state support for provisions such as education or healthcare. However, the growing crisis and deteriorating standards of living over the past couple of years has seen a rise in far-right nationalism.

Some of the protesters targeting migrants and refugees have shamefully included self-proclaimed ‘socialist Republicans’, who are propagating the narrative that the enemy of poor and working class people in Ireland are the people fleeing terror, war and destruction. A statement signed by 90 Irish Republican political ex-prisoners made clear: ‘Irish Republicanism has no affinity with the crude ‘nationalist’ hatred recently being peddled by racist and fascist groups stirring up anti-immigrant feeling… These groups are directly influenced by loyalists and British neo-nazis and other far-right elements… We call on all Irish republicans of all ages, groups and traditions to become active in your community, workplace and the streets “to try and stem the rising fascist tide”.’

Ria Aibhilin