2 March 2017 saw elections held to the Northern Ireland Assembly for the second time in ten months – this time around the result was quite different. Turnout overall was up almost 10% compared with May 2016 and was highest in Nationalist areas. The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) was returned as the largest party – but only just. Sinn Fein’s total of first preference votes leapt by 34.5%. It finished with 27 seats to the DUP’s 28 – just over 1,000 votes separated the two. It has been hailed as the Nationalists’ greatest electoral performance in the history of the statelet – and the Unionists’ worst. Mike Nesbitt resigned as leader of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) before the full count was even in. DUP veterans Lord Morrow and Nelson McCausland lost their seats. Sinn Fein President Gerry Adams called it a ‘watershed election’; the notion of perpetual Unionist majority ‘demolished’. His party has since climbed in the opinion polls in the south, overtaking Fine Gael. Talk abounds of border polls, ‘joint authority’ over the North by London and Dublin and ‘special status’ in a post-Brexit European Union.

As as of 25 March, negotiations between Sinn Fein and the DUP to restore the Executive are approaching the end of their three-week timeframe. British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland James Brokenshire has threatened to force a further election if the parties fail to reach agreement by the 27 March deadline.

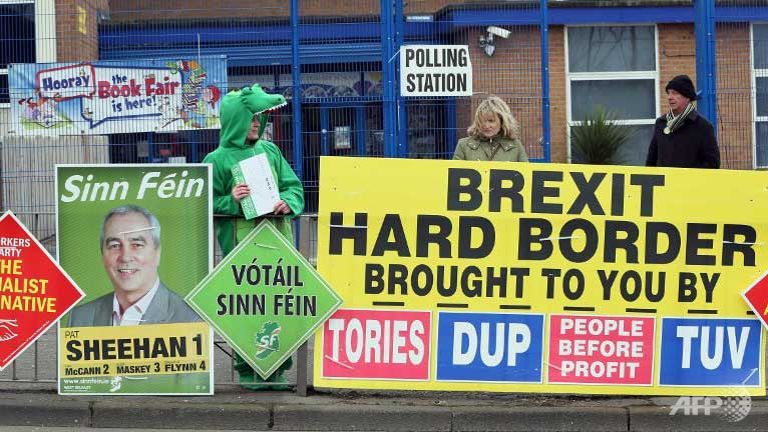

Two scandals, an election, and a crocodile

The snap poll was triggered in January when the late Martin McGuinness resigned as Deputy First Minister and Sinn Fein declined to re-nominate for the post, thus collapsing the ‘power-sharing’ Executive. This followed the eruption of the ‘cash-for-ash’ scandal the previous month in which the DUP leader, First Minister Arlene Foster, was personally implicated. That scandal followed close upon another: an exposé of the Ulster Defence Association’s role in a Stormont-funded charity.[1] With eyes on the river of public money flowing into the hands of their farmer friends and loyalist paramilitaries, the DUP’s ‘Minister for Communities’ sent season’s greetings to his nationalist neighbours with announcement of a full funding cut to a tiny Irish language scheme.

Preparations for an election began. Foster promised a ‘brutal’ campaign. Her party knew that its actions had prepared the ground for a broad anti-DUP vote and could expect to be punished even in its own heartlands – its aim was damage limitation. That meant whipping up a sectarian frenzy, designed to bring the loyalist working class to the polling booths and to check any middle class slide to the UUP. At her party’s official campaign launch on 6 February, in between ravings on Gerry Adams and ‘radical Republican agendas’, Foster cried ‘never’ to the call for Irish language legislation, telling reporters ‘if you feed a crocodile it will keep coming back and looking for more.’ Some say the DUP campaigned the only way it knows. It campaigned the only way that works. On the back of this rabble-rousing racism the party actually increased its raw vote from May 2016.

But DUP battle cries also energised the Nationalist vote. A long-term decline in turnout was significantly reversed and the combined increase in first preference votes cast for Sinn Fein and the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) was twice that of the Unionists.

No return to the status quo

Undoubtedly it was a shock for Unionism. But it will rally, and claims that its overall majority in Stormont has disappeared – even temporarily – are false. Unionism will have lost its overall majority only on a calculation that excludes the shame-faced Unionists of the ‘liberal’ Alliance Party. Anti-Nationalists will continue to dominate any future Assembly.

Sinn Fein fought the election under the slogan ‘no return to the status quo’. With its perceived momentum comes an expectation to deliver. Before the election, in her first major interview as Sinn Fein’s ‘leader in the North’, Michelle O’Neil said her party would not accept Foster at the head of an Executive with the cash-for-ash inquiry ongoing. But that was then. More recently they have downplayed this demand and insisted that talks should not be extended beyond the deadline. They say there is no need for renegotiation of previous agreements, simply implementation of commitments already made: the release of funds for ‘legacy’ inquests and ensuring the enactment of Irish language legislation and a Bill of Rights.

Westminster may well opt to extend the timeframe for negotiations. For them, direct rule is a last resort. As for Sinn Fein, it is where it is more by compulsion than design. If this is the end of power-sharing, it will not be because Sinn Fein or British imperialism wish it.

[1] See FRFI 255 for coverage of the background to the election.