Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! No. 128, December/January 1995

‘In Nigeria, we are one of the lowest — if not the lowest — cost operations within Shell.’ Brian Anderson, Managing Director, Shell Nigeria, Financial Times, 26 May 1995

‘I accuse Shell and Chevron of practising racism against the Ogoni people… I accuse the multinational companies which prospect for oil in Ogoni of genocide.’ Ken Saro-Wiwa

Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other members of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) were hanged for allegedly murdering four fellow Ogoni. MOSOP challenged the devastation of the Niger delta by oil multinationals and the Nigerian ruling class. Saro-Wiwa accused Shell of ecological war against the Ogoni. A writer and former regional government official, he was not a socialist, but a bourgeois who wanted more oil wealth for the Ogoni. However, his work and his sacrifice have brought Shell’s exploitation of Ogoniland out of the shadows. TREVOR RAYNE reports.

Ogoniland has leaking pipelines, polluted water, fountains of emulsified oil pouring into villagers’ fields, pools of sulphur, air pollution, canals driven through farmland causing flooding and disruption of fresh water supplies, footpaths blocked by pipelines, polluted wells and continual noise. Some children have never known a dark night even though they have no electricity.

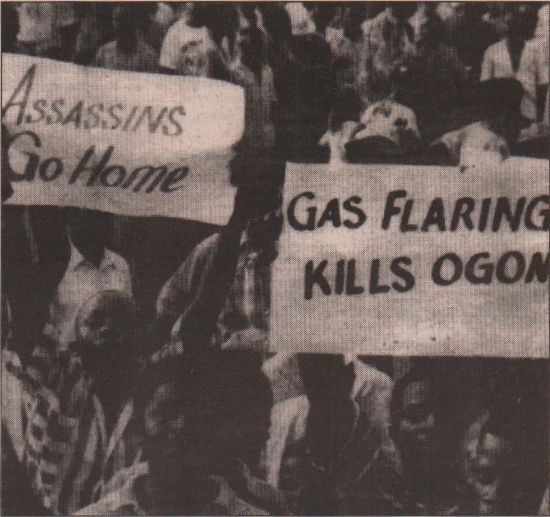

The Ogoni’s land is criss-crossed with high-pressure pipelines, yet they have no fresh running water or electricity. A people destined to be expendable. The people disagreed. In 1990 they protested against Shell. Eighty villagers were killed by the state police. Saro-Wiwa joined MOSOP. On 4 January 1993 300,000 Ogoni protested at the destruction of their lives; 300,000 out of 500,000 Ogoni people. Saro-Wiwa said, ‘On 4 January the alarm bells rang in the ears of Shell. I was to know no peace from then. I became a regular guest of the security agencies.’

Shell withdrew from Ogoniland. A leaked memo on communications between the Nigerian government and Shell remarked on the need for ‘ruthless military operations’ if ‘smooth economic activities’ were to commence. Operation Restore Order in Ogoniland has been run by Major Paul Okuntimo who told the Nigerian press that he knew 204 ways to kill but had only practised three. He hoped the Ogoni would give him the opportunity to expand his repertoire. Since 1993 some 2,000 people have been killed. Ken Saro-Wiwa was imprisoned in May 1994 and hanged on 10 November 1995. Within one week Shell announced it was going ahead with a $3.6 billion liquefied natural gas project in Ogoniland.

The Commonwealth Conference suspended Nigeria for two years pending elections; General Abacha has scheduled them for three years hence. A Nigerian soccer team was expelled from South Africa. Nelson Mandela, having preferred ‘quiet diplomacy’ to appeals from the Nigerian democratic opposition for a tough stance, was humiliated and angrily changed tack calling for sanctions.

We’re going well…

Shell is the world’s leading oil and gas producer with more reserves than any other company. Its 1994 sales of $131.5 billion exceed the national product of all but 23 countries in the world. Shell operates 1,500 subsidiaries in 128 countries, including 35 in Africa. Shell has a monopoly in oil, gas, chemicals and seed production.

The Economist’s 18 November editorial was indignant: ‘The current gang, under General Sani Abacha, are the worst: repressive, visionless and so corrupt that a parasite of corruption has almost eaten the host. These days the main activity of the state is embezzlement.’ No word that much of the money is laundered through British banks charging 20 per cent commission, but strong stuff. However, says The Economist, ‘Shell is the wrong target’ for protests; an international effort must be made to construct a viable alternative to the Abacha regime. Similar sentiments echo in the Financial Times.

This measured appraisal is done in the icy waters of financial calculation. The Pearson group, which owns The Economist and Financial Times, is a major shareholder in Shell and Lazards bank, which has interlocking directorships with Shell. Shell is at the heart of British capitalism: here meet the handful of bankers, industrialists, soldiers, politicians, and bureaucrats who run Britain.

We’re going Shell…

Royal Dutch Shell was formed in 1907 from the Royal Dutch Petroleum Company and the Shell Transport and Trading Company. The combination of Shell’s Russian and US oil trade with Dutch East Indies’ supplies was to compete with Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. Rothschild’s bank funded the new company. Sir Henri Deterding, first head of Royal Dutch Shell, ‘ended up a megalomaniac and a convinced Nazi, and the company now tries to bury his memory: no biography has been written, no records revealed.’ (Anthony Sampson)

Shell’s history is too vast for this article, but glimpses give an idea.

Weetman Pearson, later Lord Cowdray, spent £5 million on land concessions in Mexico. Huge reserves were found in 1908. Mexican oil played a key role in Britain’s First World War and it made Lord Cowdray one of the richest men in the country. Today the Pearson group extends into Penguin Books, Madame Tussauds and Royal Doulton. Cowdray sold into Shell in 1919.

Shell developed Venezuelan oil production. Workers lived in company towns with appalling conditions. Early demands were for running water and sanitation. A union was formed in 1931, then crushed with its leaders imprisoned a few days before an intended strike. At a 1956 Caracas international oil conference a Dutch labour delegate spoke out against the repression of the workers. The conference was immediately suspended and Venezuela withdrew from the International Labour Organisation, sponsors of the event. Shell transported Venezuelan oil to refineries in the Caribbean. In 1969 oil workers in the Dutch Antilles protested; troops were dispatched from the Netherlands to suppress them.

Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson announced sanctions against Unilaterally Declared Independent Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) in 1965. Shell had no intention of observing them. The then British head of Shell, Sir Frank McFadzean, argued for resumed arms sales to South Africa. Shell’s Maputo terminal was used to smuggle oil to the Rhodesian racists. By 1974, when it was clear that FRELIMO would win in Mozambique, Shell organised bogus intermediary firms and swap deals with the French company Total to keep the Smith regime supplied via South Africa. This was done with Whitehall’s assistance.

Disregarding the Oil Producing and Exporting Countries’ (OPEC) boycott and UN sanctions against South Africa, Shell and British Petroleum kept oil supplies running. South Africa imported over 80 per cent of its oil. Shell was integral to apartheid’s military potential. Before becoming National Coal Board Chairman in 1983 Ian MacGregor was a director of Lazard Freres in New York, a position he retained throughout the 1984-85 miner’s strike. Lazards in London and New York are financially interwoven. Before the strike Shell, tied to Lazards and Pearsons, lobbied in London and Washington for increased coal imports into Britain.

Shell has derecognised the TGWU at its Essex Shell Haven refinery and opposes unions on its North Sea rigs. It has built roads across the Amazon and taken out concessions on Crow Indian land in the USA.

Shell Nigeria

The search for Nigerian oil began in 1908. It became systematic after the nationalisation of the Suez Canal in 1956. British Middle East oil supplies were endangered so alternative sources were sought. Shell Nigeria’s first oil exports came in 1958. The oil was high quality and cheap, being close to sea terminals.

Today, oil accounts for 90 per cent of Nigeria’s exports and 80 per cent of government revenue. Shell produces half of Nigeria’s oil. In 25 years Nigerian oil exports have been worth $210 billion. $30 billion has been pumped out of Ogoniland, most of it by Shell. 1.1bn cubic feet of gas is flared daily in the Niger delta, hence the endless fires. Land, air and water are poisoned, yet hardly a cent of compensation has been paid by Shell.

Nigeria represents 14 per cent of Shell’s worldwide production and is its third largest oil source. $500 million had already been spent on technical appraisals and four ships to carry liquefied natural gas from the Niger delta to southern Europe. The scale of Shell’s commitment to Nigeria meant it could not easily pull out of the gas project, despite embarrassment at the hangings.

You can be sure of Shell…

Shell knew its Nigerian operations could turn into a public relations nightmare. In the 1950-60s Shell produced classroom posters showing fauna and flora of the English counties. Its British television advertisements have rabbits and foxes running through buttercup fields beneath which runs a Shell pipeline: ‘Can we develop the industry we need without destroying our countryside? You can be sure of Shell.’ This company builds sponsorships and charity donations into its annual marketing budgets as public relations exercises.

Shell is busy on the environmental discussion circuit; befitting its considerable contribution to the greenhouse effect. Shell and other oil, coal and car producers, fund the plausible sounding Global Climate Coalition to stop any measures which limit the use of fossil fuels. Shell supports the Business Council for Sustainable Development, an alliance of 43 multinational corporations. During the 1992 Rio Earth Summit its representative told Brazilian television that all the oil on the planet could be burned with impunity.

Shell must anaesthetise people to the damage it does. Its motto is ‘never apologise and rarely explain’ — never be seen at the scene of the crime, pay someone else to do it.

‘Princes should devolve all matters of responsibility upon others, take upon themselves only those of grace.’ (Machiavelli) And as fine an aristocracy of money as you could buy anywhere graces the boards of Shell. Not here Major Paul Okuntimo, but rather Robert McNamara, former US Secretary of Defence, former President of the Ford Motor Company, former President of the World Bank and then director of Royal Dutch Shell.

Interlocking directorships express the concentration of capital into very few hands and the fusion of banking and industrial capital. Directors of the British arm of Shell include directors from Rothschilds, Lazards, the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, Sun Life Assurance, BAT Industries, RTZ, Hawker Siddeley, Booker plc, Inchcape etc. Also present are the former head of the diplomatic service, the former head of the civil service, the Professor of War Studies at All Souls, Oxford and the Provost of Eton. These and many more titles are the domain of just nine men. They are the ones who requisition the weapons supplied by Britain to the Abacha regime. They are the ones who order the British and Dutch governments to veto European Union moves to impose sanctions on Nigeria.

This is finance capital, the monopolists who rotate their careers through officer high command, boardrooms and government departments. Fax them the British, US and Nigerian governments are but executive committees. They are enemies of workers and poor people everywhere. They must be exposed, their machinations must be nailed and finally they must be fought and overcome. Saving the planet means fighting the multinationals — fighting imperialism. Boycott Shell!