Ninety years ago, during September 1932, the working class of Birkenhead, across the River Mersey from Liverpool, rose up against a system which was driving tens of thousands of families into destitution. Over a period of a week, they fought the police in pitched battles as they pursued their basic demand for a 25% increase in the locally-determined level of the dole. In the end, they were victorious: the local Public Assistance Committee (PAC), a sub-committee of the council, had to capitulate. Across the country, similar battles were fought by the unemployed over the following weeks. Even in Belfast, for a very brief period, nationalist and loyalist workers came together to fight the dreaded Means Test which the National Government had introduced the previous year. ELLIE O’HARA and ROBERT CLOUGH report.

The events of that week are not just of historical interest, but have a direct relevance today as the working class faces an onslaught on its living conditions due to inflation in general and the soaring cost of household energy in particular. That the people of Birkenhead were able to secure a victory depended on an organisation which clearly represented their interests, the National Unemployed Workers’ Movement (NUWM), and the leadership that was provided by communists. The NUWM had proved necessary because the unemployed were regarded with disdain, and indeed hostility, by the Labour Party and the official trade union movement throughout the inter-war period.

These attitudes have never disappeared. Today, the Enough is Enough campaign calls for ‘reinstating the £20-a-week Universal Credit uplift’ – as if returning to what the Tory government had been forced to give during the pandemic lockdowns would be a mark of progress. It was current Labour Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves who proclaimed in 2015 that Labour was ‘not the party of people on benefits.’ Two years earlier, she boasted that Labour would be tougher than the Tories, and that ‘nobody should be under any illusions that they are going to be able to live a life on benefits under a Labour government’.

The NUWM

The NUWM was founded in April 1921, coincidentally on the same day that the transport and rail unions in the Triple Alliance with the miners capitulated and abandoned a strike in support of the miners that they had agreed to just two days earlier. This was a period of high unemployment that followed a brief boom at the end of the First Imperialist War in 1918. Three months earlier, the Labour Party and the TUC had held a conference to discuss unemployment, but had not only refused to hear from the unemployed themselves, but had also kept the meeting place a secret to prevent any protests. This was a foretaste of the political battles that the unemployed and the NUWM would have with the official labour movement during the inter-war years.

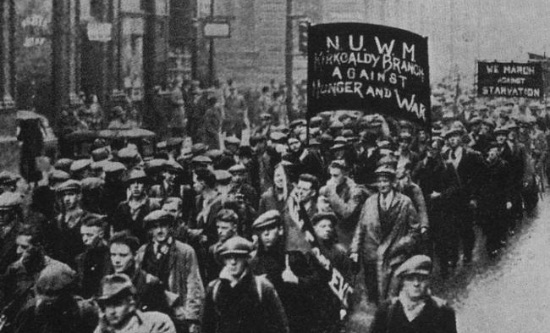

From the outset, the NUWM was a militant, street and community organisation based on local branches and led by members of the Communist Party. It would organise local protests, defend those who were victims of the ‘not genuinely seeking work’ clause, and later of the decisions made by Public Assistance Committees (PACs), using the Means Test introduced in 1931, an assessment of the material possessions and financial position of the family undertaken by the PAC. The NUWM also established centres for the unemployed and sought to organise them into a fighting force and led national marches from places of high unemployment to London. These marches took place between 1922 and 1936. The largest, against the Means Test, was in 1932 and ended in a pitched battle between over 100,000 workers and police in London.

The NUWM also fought the continuous reductions in both the level of benefits, and eligibility for them. One example was the 1927 report of the Blanesburgh Committee which recommended limits on the period over which claimants could receive benefits, new contribution rules which would exclude seasonal workers and the long-term unemployed, and required claimants to give positive evidence of seeking work. Three Labour Party representatives on the committee endorsed the committee’s report, including Margaret Bondfield who would become Minister of Labour in the 1929-31 Labour government. The TUC and Labour leaderships were to order affiliates not to support either the 1927 NUWM national march of miners, or the 1929 march directed specifically against the ‘not genuinely seeking work’ clause. The Labour government continued to enforce this clause as well as ‘test and task’ work by able-bodied claimants which was a form of forced labour.

Birkenhead NUWM

Birkenhead NUWM was established in 1922 by Joe Rawlings who had joined the newly-formed Communist Party in 1920, and had been sacked from his job as a result. Along with branches in Liverpool and Bootle it proved to be very active, and it was the Communist Party’s decision in July 1932 that it should call a protest against the Means Test that energised the NUWM’s campaign against the brutal measure. With unemployment exceeding three million, the National Government had cut unemployment benefit by 10%. It was now automatically cut off after 26 weeks to be replaced by a transitional benefit until any further benefit had been determined by the application of the Means Test.

By 1932 the unemployment rate in Birkenhead was around 30%; a large number of skilled workers had lost their jobs on the docks or at Cammell Laird shipbuilders. Nationally, nearly 400,000 of the unemployed had been excluded by the Means Test from receiving any benefit, and a further 900,000 were on transitional benefit. The first step in the Birkenhead NUWM’s campaign was to call a march for 3 August to coincide with a Town Council meeting, demanding an end to the Means Test, a 25% reduction in rents for corporation houses, and ‘relief to be granted to all able-bodied unemployed with three shillings per week increase in benefits; immediate provision of boots and clothes to necessitous unemployed; a free weekly grant of one hundredweight of coal to each family during winter months, and the application of a plan of public work schemes for the unemployed at trade union rates.’ In Birkenhead, benefit rates were substantially below the maximum level that could be set. 2,000 marched to the Town Hall in Hamilton Square, but a delegation allowed to lobby the Mayor to demand an emergency meeting to discuss the demands was stonewalled. The NUWM branch agreed to organise a further march on 7 September; 5,000 joined it but this time the Mayor refused to receive any delegation. Liverpool Communist Party leader Leo McGree made a call for the crowd to stay put until their demand to see the Mayor was met. In the end the Mayor conceded, but complained that only the council, which was meeting next on 13 September, could do anything.

On 13 September, 5,000 marched from various points across Birkenhead to be met by dozens of police behind barricades in Hamilton Square. A delegation was allowed in to speak to the council meeting; in the end, however, the council refused to meet the principal demands of the NUWM. Marchers agreed to a further demonstration in two days’ time when the PAC Ways and Means Committee was due to meet. On Thursday 15 September, an estimated 18,000 people assembled at Birkenhead Park to march to the PAC in Argyle Street by Hamilton Square. On the fringes, police started to attack the demonstrators; once again the marchers were fobbed off, with Tory councillors rejecting the right of an NUWM delegation to be in the building. Outside the PAC, Rawlings reminded the marchers that two days earlier the PAC chair, Councillor Baker, had accused the unemployed of using the dole to gamble and go to football matches, while McGree urged them to re-assemble and march to the full PAC meeting on 19 September.

As the march returned to Birkenhead Park, a group of about 2,000 decided to peel off and go to Councillor Baker’s home. McGree and Rawlings accompanied them to ensure that matters did not get out of hand, but the group was viciously attacked by the police with batons. As news of the assault spread to the main march, anger boiled over: their demands had been continuously dismissed out of hand and they were hungry and facing destitution. Tearing up park railings with which to fight the police, they made their way down to the centre of Birkenhead, smashing up shops and looting those selling food. Running battles continued into Friday morning. There was sporadic fighting later on Friday, and on early Saturday morning, Rawlings was arrested along with seven other leaders on the NUWM branch committee and remanded in custody.

In the afternoon, police broke up the weekly NUWM open air meeting at the Haymarket while protecting a fascist meeting down the road. In response, crowds gathered at Birkenhead Park only to be attacked once again by the police. Fighting continued overnight; workers took up manhole covers and laid trip wires to hinder police pursuit. Chief Constable Dawson called for reinforcements: 350 arrived from Liverpool, and 500 from Birmingham; a ferry bringing the Liverpool police across the Mersey was stoned and had to turn back. Fighting continued over Sunday night with police invading and smashing up the homes of those they suspected of being involved in organising the protests. Women threw missiles at them from upstairs windows; by the end of the fighting dozens of people had been injured or arrested. Dawson was considering whether to summon army support: the police were at breaking point.

On the Monday it was not clear what would happen. McGree had been arrested over the weekend on charges of inciting a riot, along with many other Merseyside communists. The NUWM leadership was in custody. But during the afternoon, crowds gathered outside the PAC offices to be joined by Cammell Laird workers who downed tools. Dawson himself estimated that there were around 20,000 people outside the PAC and in the surrounding streets. It was clear that the Birkenhead working class was not prepared to submit. The PAC had no choice but to back down, and agree to do what it had earlier said it could not afford, raising weekly relief scales from 12s to 15s 3d for men, and from 10s to 13s 6d for women. The Town Council set in train public work schemes for the unemployed at trade union rates, to the total value of £180,000 (tens of millions of pounds in today’s money). It was a huge victory. McGree and Rawlings were however imprisoned for 20 months for their leadership role.

Days later, massive demonstrations by the unemployed took place in Liverpool and Belfast, and the victory in Birkenhead became a stimulus for resistance across the country. In Bristol, Labour MP Sir Stafford Cripps complained: ‘What are we to say to the unemployed of Bristol who point to Birkenhead? We who are daily trying to persuade them that they will achieve nothing by rioting, that they can only achieve by constitutional action are met by the argument “What is Birkenhead?”’ He continued: ‘Is anyone going to convince the unemployed worker who is told by a communist that the only way he can force relief out of the local authority is by mass action, that these concessions have not been given as a result of force?’ Labour however had stood consistently against the unemployed, and was to continue to do so throughout the 1930s as part of its battle against the Communist Party. Today we face a situation where millions of working class families are going to be forced into ever-deeper poverty, and those in poverty, especially if they are out of work, will now face destitution. The constitutional, parliamentary methods of the Labour Party and its supporters will be no model of resistance; for that we have to point to Birkenhead in 1932.

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! No 290, October/November 2022