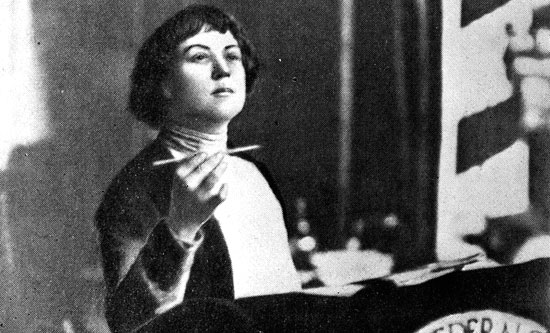

Alexandra Kollontai

It was on International Working Women’s Day in 1917 that women factory workers came out onto the streets of Petrograd and joined workers at the Putilov Works who were protesting against government food rationing. There was a growing resentment against the Tsarist regime, and women in particular wanted to show their dissatisfaction, not only with the lack of food, but with the increasingly unpopular war that had been devastating Europe for over two years. The Bolsheviks had been vocal opponents of the war since its outbreak in 1914 and this fact helped strengthen their position. Women workers came out on the streets and marched to nearby factories to recruit over 50,000 workers for strike action. The government tried to stop the demonstrations but women boldly went against the advice of their union leaders and spoke with soldiers who then refused to open fire on the demonstrations and turned their weapons instead against the Tsarist forces. The influence that women had in the February revolution was significant. The changes brought about as a result of this and the later October revolution did more to advance women’s emancipation than anything that had come before and would change the history of the world forever. Lucy Roberts reports.

Conditions in Tsarist Russia were terrible for the majority of people; there was significant overcrowding in the cities and poor sanitation. Outbreaks of disease were a regular part of life in Moscow and Petrograd especially, with life expectancy at birth being around 30 years and infant mortality exceeding twice that of many major European cities. In Imperial Russia, according to the 1897 Population Census, literate people made up 28.4% of the population. Literacy levels for women were a mere 13% and this inequality was considered natural. The revolution led to dramatic improvements in literacy rates and by 1937, the literacy rate was 86% for men and 65% for women, making a total literacy rate of 75%.

In the pre-revolutionary period, women’s lives were especially hard. From a young age women often worked long hours and received much lower pay than men, as well as being expected to carry out domestic tasks such as cooking, cleaning and weaving. Peasant women would also help in the fields when required. There was little for women outside the home, with access to government, civic and academic institutions denied. These conditions worsened as the imperialist war raged and this led women workers to demand change: it was impossible to live in the old way.

Key female Bolsheviks realised that systemic change would be needed if women’s problems were to be truly addressed. Bourgeois feminists at the time were concerned only with incremental changes like securing women’s suffrage and many wanted to limit this right to women who owned property. While the Bolsheviks were also concerned with universal suffrage, they recognised that this was not an end in itself and did not address the primarily economic basis of women’s oppression. Alexandra Kollontai, a leading socialist had this to say in 1909:

‘The more aware among proletarian women realise that neither political nor juridical equality can solve the women’s question in all its aspects. While women are compelled to sell their labour power and bear the yoke of capitalism, while the present exploitative system of producing new values continues to exist, they cannot become free and independent persons, wives who choose their husbands exclusively on the dictates of the heart, and mothers who can look without fear to the future of their children … The ultimate objective of the proletarian woman is the destruction of the old antagonistic class-based world and the construction of a new and better world in which the exploitation of man by man will have become impossible. Naturally, this ultimate objective does not exclude attempts on the part of proletarian women to achieve emancipation even within the framework of the existing bourgeois order, but the realisation of such demands is constantly blocked by obstacles erected by the capitalist system itself. Women can only be truly free and equal in a world of socialised labour, harmony and justice.’1

What Kollontai and the Bolsheviks were arguing was that it is impossible to eliminate women’s oppression under capitalism precisely because capitalist society depends on it.

In Revolutionary Communist 5 we discussed the material basis of women’s oppression under capitalism:

‘The specific oppression of women under capitalism lies in their dual role in capitalist society. Women bear the main burden of domestic work while at the same time occupying an inferior position in social production. These two aspects are mutually reinforcing. Insofar as women work in factories, offices and so on, they perform social labour. However, women as domestic workers carry out work in the home which is both separate from and integral to the process of capital accumulation. Their work is necessary for capital and yet it is outside of social production – privatised.’2

Under capitalism workers have to sell their labour power to produce commodities for capitalists. This labour power must then be replenished once the working day is over, in order that the worker can return the next day and carry on the process. Workers sell their ability to labour during the day then, upon returning home, carry out unpaid labour in order to sustain themselves and thus reproduce their ability to labour. This replenishing of labour power requires private labour to be carried out in the form of cooking, cleaning, childcare etc. Traditionally these tasks have fallen to women. However, whereas in pre-capitalist societies this would have formed part of the social labour, under capitalism this labour is privatised.

This dual oppression of women in the workplace and as domestic workers cannot not be overcome under capitalism. Only socialism can provide the material conditions to make women’s liberation possible.

Following the October revolution, the world’s first socialist state was created and as a result of this women’s emancipation leapt forward significantly. Women were recognised under law as being equal to men and many other changes were brought in to further improve the lives of women.

- Labour laws assisted women, with paid maternity leave and a minimum wage standard that was set for both men and women, health and safety protections at work, access to free health care and paid holiday leave.

- Crèches were established to allow for the socialised care of children. These did not exist in Imperial Russia and were a huge step forward, allowing women to participate in work, political, cultural and academic life for the first time.

- The USSR was the first country to legalise abortion and to provide it free of charge.

- Separation of marriage from the church allowed couples to choose a surname; divorce was reformed to be available at the request of either partner; and, significantly, ‘illegitimate’ children were given the same rights as ‘legitimate’ children, meaning that men were legally obliged to provide support for their children whether they were married or not.

For the first time, women had access to higher education, political office, the arts, culture and literature. Before 1917 university education was almost entirely confined to the nobility and professional classes. There were 91 universities, with about 112,000 students. By 1940 there were 700 universities, with 650,000 students. Women students comprised 47% of the total. These changes meant that women had access to many areas of society that had been previously denied. In 1922 women were 22% of the workforce but within ten years this figure had grown to 32%.

Socialism in Russia was a progressive force for women’s emancipation and many of these advances were groundbreaking. However, it is important to note that women’s oppression was not eliminated in the USSR. Even after all the legal and economic changes in society which freed women from many aspects of oppression they previously experienced, old ideas still persisted in people’s minds and attitudes. Assata Shakur, a former US Black Panther, commented on this after years of refuge in socialist Cuba.

‘It was clear that a revolution was not a magic wand that you wave and all of a sudden everything is transformed. The first lesson I learned was that a revolution is a process, so I was not that shocked to find sexism had not totally disappeared in Cuba, nor had racism, but that although they had not totally disappeared, the revolution was totally committed to struggling against racism and sexism in all their forms. That was, and continues to be, very important to me. It would be pure fantasy to think that all the ills, such as racism, classism or sexism, could be dealt with in 30 years. But what is realistic is that it is much easier and much more possible to struggle against those ills in a country which is dedicated to social justice and to eliminating injustice.’3

The newly formed USSR committed itself to dealing with women’s oppression and took huge steps towards achieving this despite the years of hardship and imperialist-backed civil war that followed October 1917. The new government established the Zhenotdel – the women’s department of the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party. This body promoted mass women’s organisations to tackle illiteracy and to provide education about new laws and policies throughout the Soviet Union. Representatives of the Zhenotdel would travel thousands of miles across the country in order to campaign for the revolution, setting up 125,000 literacy schools. The Zhenotdel published a monthly magazine Kommunistka which dealt specifically with issues such as sexuality, abortion and women’s liberation and linked these issues with the struggle for socialism.

The Bolsheviks realised that the revolution depends on building revolutionary consciousness and this process continues even when a socialist society is established. Today, we can look to the Cuban revolution for examples of how a modern socialist country has made progress towards equality.

Cuba is ranked third in the world in terms of most female representation in the country’s main governing body, with a Congress that is 49% female. Women currently comprise 63% of university enrolment, more than 60% of the technical and professional sector, and more than 70% of lawyers in the country. They also constitute a majority in key sectors such as health and education. In scientific research they are a significant force. In 1953 barely 12% of the female population was in paid work.

In the USSR after the revolution, as in Cuba, huge steps were made towards achieving equality which would simply have been impossible without addressing the material basis of oppression. Capitalism cannot provide emancipation for women. Only by addressing the material and economic roots of women’s oppression can we begin to build a more equal society. Only under socialism can true women’s liberation be achieved.

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! 259 August/September 2017

1. Alexandra Kollontai, Introduction to ‘The social basis of the woman question’, 1908.

2. Olivia Adamson, Carol Brown, Judith Harrison, Judy Price, ‘Women’s oppression under capitalism’, Revolutionary Communist No 5, November 1976.

3. The social basis of the woman question 131, June/July 1996.