The result of the 2024 General Election is one thing. The value of the result and the voting process itself is another and has a long history of changing views in the socialist movement. Where a political party is standing that represents the independent interests of the working class, socialists will participate in parliamentary elections. Where there is no such party as in the 2024 General Election, socialists will call for a boycott and propose other forms of political struggle. While aware of the 140 years of working-class involvement in the struggle for the vote, socialists are not uncritically tied to the institutions of the imperialist British state. SUSAN DAVIDSON reports.

Dying for the vote

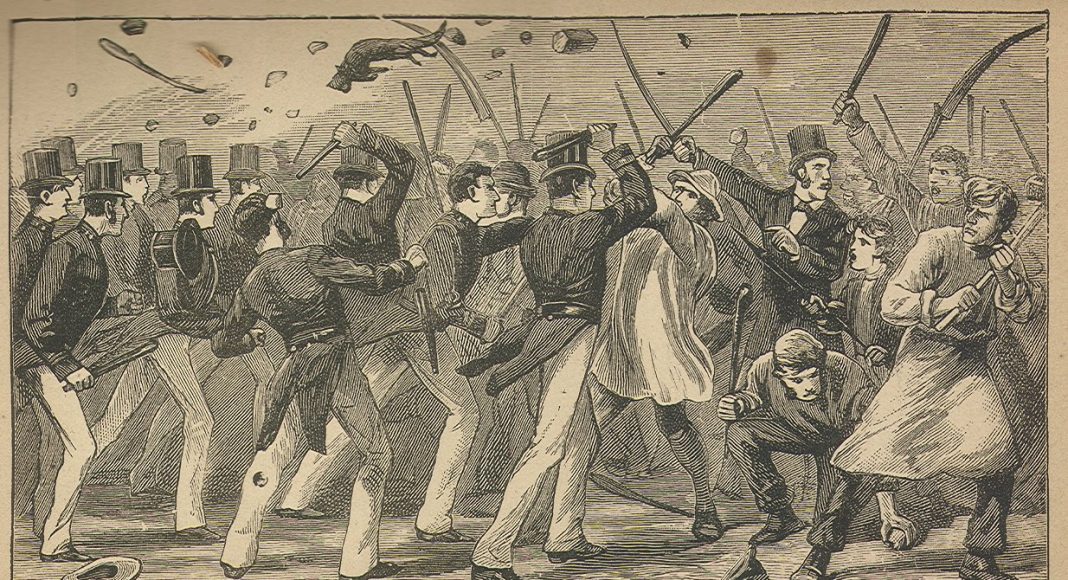

The demand for the right to vote was a demand on the British state which was won with great working class struggles and sacrifices during which many died, or rather, were killed, which is a measure of how resistant the state was to extend the vote. The first mass working class demonstration for universal male suffrage took place in 1819 at Peterloo in Manchester with an estimated crowd of 60,000. Although peaceful the meeting was attacked by the military resulting in 17 deaths and 700 badly injured people. Thirteen years later the aristocratic ruling class passed what was called the Great Reform Act of 1832. This conceded the vote to accommodate the rising capitalist bourgeois class of industrialists, small landowners, shopkeepers, and male householders paying more than £10 in annual rents.

The Chartists

The industrial revolution resulted in the rapid emergence of a new proletarian class of workers driven into towns and factories, creating social turmoil and a growing class consciousness. Angry at the property qualifications on the right to vote, the Chartists, the first mass working class movement, mobilised many thousands of people across the country demanding universal male suffrage. In each year of 1839, 1842 and 1848, massive Charters, the last with up to three million signatures, were rolled to parliament by huge processions of men and women. Each time their petitions were rejected and the crowd were charged and scattered by the military. In 1839 alone 22 Chartists were killed, 50 injured and three leaders were sentenced to be hung, drawn, and quartered, later commuted to transportation to Australia. Altogether more than 102 Chartists were transported to Australia, some as young as 16 years.

During these nine years of struggle and failure the Chartist movement split into two camps, the ‘moral force’ group, which lobbied influential individuals, and the physical force school led by Feargus O’Connor, editor of The Northern Star, a weekly Chartist newspaper.[1] A great orator and organiser, O’Connor was elected to Parliament himself in 1847 where he tried to promote his own solution for poverty with a ‘land-plan’ that would force landowners to lease farmland to the army of rural unemployed. While riots continued to break out around the country in protest at cruel conditions and hunger, the Chartist movement gradually folded. The Chartist leaders were anyway moving away from the purely constitutional demand for the vote and promoted other ways to help the poor. For example, Robert Owen (1771-1858) was a leading example of what Karl Marx was to call the Utopian socialist school who regarded the class of proletarians as ‘the most suffering class’. Owen established communities to live, work and support each other. The working class was viewed as ‘a class without any historical initiative or independent political movement.’[2]

The revolutions of 1848

Owen’s version of an enlightened and fair society, far removed from class antagonism, was challenged by events in 1848 when revolutions broke out in several European countries where the bourgeois class was denied parliamentary representation even to the limited extent of Britain. It was in this great rebellion against autocracy, led by the middle class and supported by the slowly growing number of workers arising from the peasantry, that Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels saw the advance of communism. ‘A spectre is haunting Europe, the spectre of Communism’ are the opening words of the Communist Manifesto, 1847. The politics of the struggle shifted with Marx’s explanation of the economic foundations of the class system. He identified capitalism as a historic epoch of private property, of production for profit and exploitation of a class of workers.

The Communist Manifesto 1847

Marx and Engels were commissioned to write a Manifesto for the Communist League, a newly established grouping combining elements of workers’ movements, independence struggles and democratic associations in Belgium, Germany, Scandinavia, Hungary, Switzerland, Portugal, and the Polish national movement. The frenzied political turmoil of these years was decidedly internationalist and encouraged by Chartist Northern Star radicals like George Julian Harney who had long supported the Irish liberation struggle recognising it as a common cause against the joint oppressor, the British state. As Harney said, ‘People were beginning to understand that foreign as well as domestic questions do affect them…Let the working men of Europe advance together.’[3]

Although written and published shortly before the dramatic outbreak of the uprisings in Europe, the Communist Manifesto had no immediate impact on events as such – its message of class struggle was only slowly understood and taken up after the defeat of the 1848 attempts to overthrow European autocracies.

The influence of the Communist Manifesto slowly grew. This was where Marx and Engels made their first consistent effort to establish some of the principles upon which a socialist movement could be built. Engels was later to point out the limitations of the manifesto, as in the 1888 Preface to the English Edition where he writes, ‘It was a product of particular historical conditions, but the fundamental proposition holds true, that in every historical epoch, the prevailing mode of production and exchange, and the social organisation necessarily following from it, form the basis upon which is built up, and from which alone can be explained the political and intellectual history of that epoch; that consequently the whole history of mankind. . . has been a history of class struggles, contests between exploiting and exploited, ruling and oppressed classes’.[4] This remains true as long as the capitalist system remains.

The concept of antagonistic class interests took root in the political movements that grew after the defeat of the 1848 revolutions. The Paris Commune of 1871 rose to assert the rights of the working class against both the French state and invading German military forces. Following the defeat of the Commune the ruling class took bloody revenge with 6,667 confirmed killed and buried, and unconfirmed estimates of the number taken prisoner from 15,000 to as high as 43,000, with a further 6,500 to 7,500 self-exiled abroad. On reviving after this slaughter, the left divided into two main groupings: the anarchists led by Mikhail Bakunin who sought to by-pass the state altogether; and the social democrats who built reformist parties to put gradual pressure on the state for the rights and welfare of the working class.

Votes for Women

Women’s struggle for the vote has taken place and been achieved in most countries of the world. In each case the struggle for the franchise had to overcome established religious hierarchies and patriarchal practices.[5] Within the well-known suffragette movement of Britain there were splits and differences along revolutionary and reformist lines. Sylvia Pankhurst spent many years organising, demonstrating, and going on repeated hunger strikes in pursuit of the franchise for women. She turned away from this purely constitutional demand as she became conscious as a communist, that for working class women, disenfranchisement was only one of the many injustices that were inflicted upon their lives by the ruling class. She organised in the East End of London for women’s rights to support for nurseries, equal pay, decent housing conditions and all the other advances so evidently needed to protect women and prevent them from being driven into prostitution as the only means of livelihood.

Universal voting rights at last!

After the 1914-1918 war the British ruling class felt the rising pressure of working class demands and conceded a place in the state for the bourgeois democratic Labour Party which formed its first government in 1924. Concessions were granted: the 1918 Representation of the People Act removed practically all property requirements for men over 21 and allowed men in the armed forces the vote from the age of 19. Women over 30 years were given the vote as a reward for dropping their demand for the franchise out of patriotic loyalty and providing stalwart war work. This was finally extended in the 1928 Equal Franchise Act granting women the same voting rights as men at the age of 21 years. The British state continues to deny voting rights to convicted prisoners serving a custodial sentence although the European Court of Human Rights has contested this over time. Scotland and the north of Ireland have devolved governments. Homeless people can get onto the electoral register but must provide an address where they spend most of their time. In 2024 personal identification was introduced as a new qualification to use the vote. The numbers of people disqualified or unable to organise their participation in parliamentary elections every five years or so has not been calculated.

And the vote today?

Of the original six demands of the Chartists five have been won: universal male suffrage, equal electoral districts, vote by ballot, wages for Members of Parliament, and abolition of the property qualifications for MPs. The sixth on the list, annually elected Parliaments, has not been achieved. This demand is the truly radical basis for a representational government: as Marx pointed out in his 1871 work on the Paris Commune, The Civil War in France, it makes accountability and the right of recall central in the voting process and would put MPs under the direct control of their constituents. The vote today gives no such real power to the voters despite the consolidation of the capitalist state as central to the existing order. The modern state can nationalise industries, provide universal education and healthcare systems, provide a cascading structure of regional and local government elections and budgets, local police monitoring boards, trial by jury, and a tax system that must be approved by parliament. Yet these changes have not fundamentally affected the balance of class forces in this country or elsewhere and the capitalist class remains firmly in power. They determine foreign policy, military engagement, immigration criteria, and, together with their class allies in the finance sector, investment priorities. No parliamentary party stands against this established class order.

The Communist Manifesto ends, famously, with the words, ‘The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Workers of all countries unite!’ The road to the vote has not proved to be the road to the self-emancipation and self-organisation of the working class. Rather it has become one of the chains that bind the working class to nationalism, racism, and subservience to the state institutions of the bourgeoisie. That is why this newspaper stands by its bold slogan of today, Don’t Vote! Organise!

[1] Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! no 27, March 1983.

[2] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party, pp89-90, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1967.

[3] George Julian Harney, Northern Star, February 26,1848. Quoted in Theodore Rothstein, From Chartism to Labourism, 1929, pp136-7.

[4] Marx and Engels, op cit, pp20-21.

[5] See Women’s oppression under capitalism, Larkin Publications, 2021.