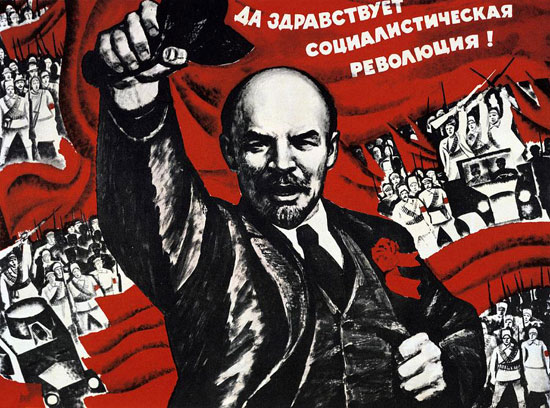

Centenary the Bolshevik Revolution 1917–2017

In 2017 we celebrate the 100th anniversary of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution and the beginning of the most important struggle for socialism, peace and progress in history. Throughout the year, FRFI has carried articles analysing the lessons of the Bolshevik Revolution. In FRFI 259 we examined the developments up to Kornilov’s attempted coup in August 1917. Below, we conclude the series with an article by Patrick Newman first published in FRFI 72 in October 1987, which looks at the momentous events of the October Revolution.

October

Lenin now realised that the time had come for an armed uprising in Petrograd and Moscow, the seizure of power and the overthrow of the government. The majority of the people were on the side of the Bolsheviks.

Kornilov’s attempted coup had been thwarted, yet the forces backing it – the industrialists, the bourgeois parties and the Allies – were undefeated. The conspirators were kept in reserve for another attempt. Only five arrests were made, and Kornilov placed under merely nominal detention. Events were moving rapidly towards the October revolution – the seizure of state power.

Only for a moment, it seemed as if power might still pass peacefully into the hands of the workers and peasants. In the aftermath of the coup, the Menshevik-SRs, fearing complete compromise in the eyes of the masses, decided not to collaborate any longer with the Kadets. On 1 September Lenin considered offering ‘by way of exception’ a compromise, to return to the demand for all power to the Soviets and a Menshevik-SR government responsible to the Soviets.

But on the very next day the Menshevik-SRs resolved to support a new cabinet, consisting of Kerensky and members of the Kadet party. Even then, to ensure that all possibilities of a peaceful road were fully exhausted, Lenin continued to entertain the possibility of a compromise for about the first ten days of September.

But in fact the moment had passed. Lenin now realised that the time had come for an armed uprising in Petrograd and Moscow, the seizure of power and the overthrow of the government. The majority of the people were on the side of the Bolsheviks; and the impending surrender of Petrograd to the Germans would make the chances of insurrection ‘a hundred times less favourable.’ Was Lenin correct?

In the factories, the elections to the factory committees and trade unions showed that the majority of the workers supported the Bolsheviks. Even in the most backward factories, workers who had previously supported the war now swung to the Bolsheviks, sometimes in a very dramatic way: ‘… a former defencist worker mounted the rostrum and with tears in his eyes begged forgiveness from his comrades, promising personally to wring Kerensky’s neck. Another appeared with a huge portrait of Kerensky, which he proceeded to tear to shreds before the assembly.’

In the Soviets, during the first week of September, there was a series of resolutions in favour of a government of the Soviets – in Petrograd, Finland, Moscow, and Kiev. Furthermore, the masses were beginning to identify with the Bolsheviks as a party and not merely to support their resolutions. On 9 September the Bolsheviks won their first decisive victory in the Petrograd Soviet; and a Bolshevik, Trotsky, was elected chair.

In the countryside, the number of attacks on landlords’ properties rose by one-third compared to August. The conflicts took on a more bitter form – burning manor-houses, cutting down landlords’ forests – with soldiers on leave becoming increasingly prominent. The peasants were beginning to realise that they would not be given land by the SRs, they would have to take it for themselves.

The bourgeoisie was considering a surrender of Petrograd, the removal of the government to Moscow and the conclusion of a separate peace. This would enable it to disperse the Soviets and the Constituent Assembly. In bourgeois circles it was common to prefer a victory for the German Emperor rather than for the Bolsheviks; and the intelligentsia contemptuously referred to the Soviets of Dogs Deputies.

As their first move, from the beginning of September, the industrialists launched a full-scale offensive against the factory committees, closing down factories and dismissing the workforce. They were encouraged by the Menshevik Minister of Labour’s circulars restricting committee meetings to outside work hours and abolishing their right over hiring and firing.

‘The bony hand of hunger’ grasped the workers by the throat. In August and September workers demonstrated under the slogan ‘we are starving’ while the bourgeoisie gorged itself unceasingly. The working class was being destroyed physically as the capitalists attempted to starve them into submission.

Lenin was right. These were the most favourable conditions for insurrection: the people were determined to fight, the vacillations in the ranks of the enemies and the half-hearted friends of the revolution were at their greatest. The aim must be to seize power before the forthcoming Soviet Congress to forestall any attempt by the bourgeoisie to disperse the Soviets.

The precise timing of the insurrection should be decided by those in direct contact with the workers and soldiers. In the short term, the Bolsheviks should use the impending Democratic Conference to make a brief, trenchant declaration and then despatch the entire group of delegates to the factories and the barracks. At the same time the technical preparation for the insurrection must be taken in hand immediately.

Still in hiding, with a price on his head, Lenin wrote two letters (12, 14 September) to the General Committee explaining his position. The Bolshevik leaders were stunned by the urgency of his demands to prepare the insurrection. At the Central Committee of 15 September, they voted 6-4 to keep only one copy of the letters, and to burn the rest. Stalin’s suggestion that, in line with Lenin’s request, copies be sent to other party committees, was rejected. With guilty embarrassment, Lenin’s views were put aside.

Pre-Parliamentary idiocy

The Bolshevik leaders continued to follow the path of compromise with the Menshevik-SRs at the Democratic State Conference (14-21 September), held in Moscow to discuss the nature of the future Government. Unlike the conference held a month previously, there were no Kadets, but the Bolsheviks were admitted.

The conference was a complete fiasco. The first vote on the principle of coalition with the bourgeoisie won by 766 votes to 688; an amendment excluding the Kadets also won, by 595 to 493. Four days of heated debate settled absolutely nothing.

One final act remained in the comedy of ‘democratic’ manners: the Pre-Parliament. Before dispersing, the Conference appointed a permanent body, with the possessing classes significantly overrepresented, which was to represent the nation until the Constituent Assembly: the Pre-Parliament was due to open on 7 October.

What were the Bolsheviks doing? The Conference delegation had fully participated in the Conference, and, worse still, voted by 77 to 50 (with Stalin and Trotsky against) to participate in the Pre-Parliament.

The Bolshevik policy was now to campaign for a transfer of power to the Soviets at the next Soviet Congress, 20 October. In the Bolshevik paper, Workers Path, Zinoviev made this appeal (30 September): ‘Let’s concentrate all our energies on preparations for the Congress of Soviets; it alone will assure that the Constituent Assembly will be convened and carry forth its revolutionary work.’

Lenin knew that the party was letting slip what might be its last chance. His article (22 September) for Workers Path on ‘Mistakes of the Bolsheviks’ argued that 99% of the Bolsheviks should have walked out of the Conference, going directly to the factories and barracks. Instead of bringing the workers to demonstrate outside the Conference, they should have gone to the workers. The editors (including Kamenev, Stalin and Trotsky) printed his article with all these criticisms omitted.

In his next article, bearing the same title, Lenin praised Trotsky for proposing a boycott. This time the editors suppressed the article completely, publishing instead an article written at the beginning of September, when Lenin had believed that a compromise was still possible. The Central Committee persistently left unanswered Lenin’s requests that his policy be considered.

Lenin was now mortally afraid that the Party would have ‘beautiful resolutions, but no power’. The Russian Revolution was part of the world revolutionary movement, which had entered a decisive phase, with mutinies in the German fleet (August 1917), and disturbances in almost every European country. If the Bolsheviks did not organise to take power before the Congress of the Soviets it would be ‘utter idiocy, or sheer treachery,’ and they would be ‘miserable traitors’ to the revolutionary cause.

He was so incensed by the Central Committee’s failure even to consider his position, that he offered to resign, reserving freedom to campaign among the rank and file of the Party and at the party congress.

This was not necessary. Under pressure from below, particularly from the Petrograd factory workers, the Central Committee was forced to reconsider its position. On 5 October, with one against (Kamenev), it was decided to stage a walk-out at the opening session of the Pre-Parliament, taking a hesitant step towards insurrection.

The Pre-Parliament opened on 7 October in the grandiose Mariinsky Palace, surroundings calculated to have a soothing effect on weary Mensheviks, such as Sukhanov: ‘Amid all this magnificence, one wanted to rest, to forget about labour and struggle, about hunger and war .. . about the country and the revolution.’

The Bolsheviks did not forget about the revolution: Trotsky denounced the Pre-Parliament, called for all power to the Soviets, and led the Bolsheviks out. But what was their next move?

The decisive push towards insurrection came on 10 October, when Lenin succeeded in convincing a Central Committee meeting that the situation was fully ripe for the seizure of power.

This time Lenin was opposed only by Kamenev and Zinoviev. They supported a campaign for the strongest possible representation at the Constituent Assembly. They accepted the need for an insurrection, but disagreed about the ‘timing’, in practice postponing it to the indefinite future. This was because they doubted that the Bolsheviks had the support of the peasantry; they feared that the international proletariat would not support the Russian revolution; and they claimed that the workers were not straining at the leash but apathetic.

To all appearances, their claim had some justification. There were few visible signs of a readiness for action: between August and October in Petrograd only 10% of the workers were involved in strikes; attendance at meetings was sporadic; and factory organisers reported that the general mood was one of lethargy.

But Lenin divined the fundamental aspirations of the masses beneath their shifting moods. The workers were prepared to risk everything – unemployment, starvation, and even death – but were not interested in partial actions such as economic strikes, meetings or demonstrations. Thus workers at the Moscow Dynamo factory reported that they: ‘… do not want to conduct an economic strike. But for political gains they are unanimously prepared to come out … playing with words destroys all that is left and only irritates the hungry proletarian working class.’

The Congress was only ten days away – the Bolsheviks were now politically prepared, but technically unready.

They were spurred on by their enemies. In the second week of October, the Provisional Government suddenly announced plans to move most of the Petrograd garrison to the front, following the German success in driving the Baltic Fleet into the Finnish Gulf. On 9 October the Menshevik-SRs proposed a special committee to prepare for the defence of Petrograd. The Bolsheviks agreed that a Military Revolutionary Committee (MRC) be set up for this purpose. Its effective leaders – Trotsky and Antonov – were both Bolsheviks. Under the camouflage of preparing for the defence of Petrograd, they could prepare for the insurrection.

The Bolsheviks had more to worry about from their own side than from the opposition. Kamenev and Zinoviev did not limit themselves to a dissenting opinion, but proved themselves to be strike-breakers. They used the 18 October issue of New Life (an anti-Bolshevik journal) to attack their own party: ‘… taking the initiative of an armed insurrection at the given moment, with the given correlation of forces, independently of and a few days before the Soviet Congress – would be inadmissible and fatal to both the proletariat and the revolution.’

However, the mass of the Bolshevik party worked for, not against, the insurrection. They received an unexpected favour from the Mensheviks, who postponed the Congress for five days, to 25 October. With only six days to go, the MRC began to operate.

The disposition of forces in the approaching battle was as follows. Of the 200,000 soldiers in the garrison, about 10,000 (including 5,000 officer cadets) were decidedly hostile, the vast majority are passively sympathetic. On the side of the insurgents are an estimated 34,000 Red Guards, utterly dedicated but not very well armed. The typical Red Guard was a factory worker, aged under 26, and a Bolshevik.

Insurrectionary days

20 October: The MRC sends out key combat units against a provocative planned march by the Cossacks. The march is cancelled. It then directly challenges the Provisional Government: only those directives to the garrison signed by the MRC should be considered valid. The authorities yield without a struggle. In general, they remain passive and make no serious efforts at counter-mobilisation.

22 October: The day of the Petrograd Soviet, a celebration of Soviet power. Hear the simplicity and eloquence of the great Bolshevik orators – Lunacharsky, Trotsky, and Volodarsky – in Trotsky’s speech: ‘The Soviet regime will give everything that is in the country to the poor and to the people in the trenches. You, bourgeois, have two coats – hand over one to the soldier who is cold in the trenches. You have warm boots? Sit at home; the worker needs your boots.’

23 October: The Peter-Paul Fortress has to be won over for its well-stocked arsenal and because its cannon overlook the Winter Palace. Antonov is for taking it by force, but Trotsky thinks that the force of words will be enough. He is right – following his speech, the Fortress agrees to accept only the orders of the MRC and to hand over control of the arsenal.

Rather late in the day, an armed guard is put around the Bolshevik political and military HQ – Smolny Institute.

24 October: The Government makes its only show of force. At 6am Junkers break up the printing press of Workers Path; the cruiser Aurora is ordered to leave Petrograd. On the command of the MRC, Lithuanian soldiers reopen the printing house; the sailors rise against their officers. It is noticeable how often among the soldiers the national minorities take the lead.

Early in the evening officer cadets attempt to raise the bridges which link central Petrograd with the working class districts and so cut off access to Smolny. They are driven off without casualties by a crowd of armed citizens.

A dozen sailors capture the telegraph office without firing a shot, although there are no Bolsheviks among the 3,000 employees.

During the last week of their regime, the life of the bourgeoisie continues undisturbed. In his matchless description of these days (Ten Days That Shook The World) John Reed reports that as well as weekly exhibitions of painting ‘… hordes of the female intelligentsia went to hear lectures on Art, Literature, and the Easy Philosophies. It was a particularly active season for Theosophists.’

A fashion for mysticism is complemented by frenetic attempts to ignore the yawning abyss: ‘Gambling clubs functioned hectically from dusk to dawn, with champagne flowing and stakes of twenty thousand roubles. In the centre of the city at night prostitutes in jewels and expensive furs walked up and down, crowded the cafes …’

Events still aren’t moving fast enough for Lenin. The MRC must seize the initiative instead of responding to the Government and waiting for the Soviet Congress. Of the Bolshevik leaders, Lenin alone insisted on the necessity of seizing power before the Congress. He hurries to Smolny, against the orders of the Central Committee as he is supposed to remain in hiding. His intervention is decisive and the insurrection begins within a few hours.

25 October: The beginning of an extremely prosaic insurrection, more like a changing of the guard. There are no barricades, no street fighting, no hand-to-hand clashes, and virtually no casualties.

Between 2am and 7am the key positions are secured. Two of the main railway stations are occupied; the Aurora casts anchor in a commanding position on the river Neva, and the sailors ensure control of the remaining bridges; and the telephone exchange is taken over.

At 10am the MRC issues a slightly premature declaration that the Provisional Government has been overthrown. An hour later, Kerensky leaves the capital in a car supplied by the US Embassy in a futile attempt to rally support at the front.

The final step

Yet the final step has not yet been taken: Ministers of the Provisional Government have taken refuge in the Winter Palace. The taking of this last refuge of the bourgeois regime is the nearest to an ‘heroic’ episode in the insurrection. Even so, the seizure of the Palace is a chapter of accidents and blunders – with a more resolute defence it could have been costly.

If the MRC had been fired by Lenin’s urgency it could have taken control of the Palace two or three days earlier. Now the MRC compounds its tardiness by an overcomplicated plan. Inevitably, detachments are late, instructions are confusing, orders are misunderstood.

In retrospect some of the difficulties are quite comical. At the last minute someone checks the cannon of the Peter-Paul Fortress, which are to fire on the Winter Palace. There are shells for the 6″ guns, but the barrels are dirty; so heavy 3″ guns are dragged a considerable distance – they might work, only there aren’t any shells. On a second check, the 6″ guns can be made to work after all.

The signal for the final attack is to be given by a red lantern hoisted to the top of the Fortress flagpole. The only problem is – no-one can find a red lantern. After a long search, one is found but is difficult to make visible.

The palace is defended by a scratch force of about 2,000 – a 150-strong women’s battalion brought here by a trick as they thought they were coming on parade; a small contingent of war wounded; Cossacks from a remote province; and, the largest number, young officer cadets.

No military man can be found to conduct the defence, which is entrusted to a Kadet, the Minister of Public Charities. His own party was not in a very charitable mood, so ignoring his repeated requests for help that he complained: ‘What kind of a party is this that can’t send us three hundred armed men!’ What indeed!

In the bourgeois district next to the Palace it is pleasure as usual. John Reed notices that: ‘…a few blocks away we could see the trams, the crowds, the lighted shop-windows and the electric signs of the moving-picture shows – life going on as usual.’

While the siege is in progress, the Soviet Congress begins (at 10pm). Of the 670 delegates, 300 are Bolsheviks, and over 100 left SRs (close to the Bolsheviks). Shortly after the proceedings have begun, the Mensheviks and right SRs walk out in protest against the insurrection, showing their contempt for Soviet democracy. Red Guards and soldiers infiltrate the palace via its numerous entrances. Inside the palace there are numerous inconclusive, but not bloody, encounters. Its ‘defenders’ continually drift away during the evening, while the number of insurgents grows. At 11pm the Aurora fires a blank; two hours later it begins a more regular if somewhat desultory bombardment.

It is enough. At 2.10am on 26 October the Palace is taken – power is in the hands of the Soviet Congress. After a week of hard fighting, with 500 killed, the insurrection succeeds in Moscow, the only place in Central and North Russia where the Bolsheviks encounter sustained resistance. The Bolshevik revolution has triumphed – seven decades of Soviet power have begun!

Long Live the Russian Revolution!

‘The Citizens of Russia!’ – Appeal of the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee 25 October 1917

The Provisional Government has been deposed. State power has passed into the hands of the organ of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies – the Military Revolutionary Committee, which heads the Petrograd proletariat and the garrison. The cause for which the people have fought, namely, the immediate offer of a democratic peace, the abolition of landed proprietorship, workers’ control over production, and the establishment of Soviet power – this cause has been secured. Long live the revolution of workers, soldiers and peasants!

Declaration of Rights of the Peoples of Russia,

2 November 1917

The October Revolution of workers and peasants began under the common banner of emancipation.

The peasants are emancipated from landowner rule, for there is no landed proprietorship any longer – it has been abolished. The soldiers and sailors are emancipated from the power of autocratic generals, for generals will henceforth be elected and removable. The workers are emancipated from the whims and tyranny of capitalists, for workers’ control over factories and mills will henceforth be established. All that is living and viable is emancipated from the hated bondage.

There remain only the peoples of Russia, who have been and are suffering from oppression and arbitrary rules, whose emancipation should be started immediately, and whose liberation should be conducted resolutely and irrevocably.

In the epoch of tsarism the peoples of Russia were systematically incited against one another. The results of this policy are known: massacres and pogroms, on the one side, and slavery of the peoples, on the other. There is no return to this infamous policy of incitement. From now on it is to be replaced by a policy of voluntary and sincere alliance of the peoples of Russia.

In the period of imperialism, after the February Revolution, which had given power to the Constitutional-Democrat bourgeoisie, the undisguised policy of incitement ceded place to the policy of cowardly distrust towards the peoples of Russia, the policy of petty excuses for persecution and provocation covered up with utterances about ‘freedom’ and ‘equality’ of the peoples. The results of this policy are known: increased national enmity, undermined mutual confidence.

This reprehensible policy of lie and distrust, petty persecution and provocation must be done away with. From now on it shall be replaced by an open and honest policy leading to the complete mutual confidence of the peoples of Russia.

Only this confidence can lead to a sincere and firm alliance of the peoples of Russia.

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! 260 October/November 2017