Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! no 85 – March 1989

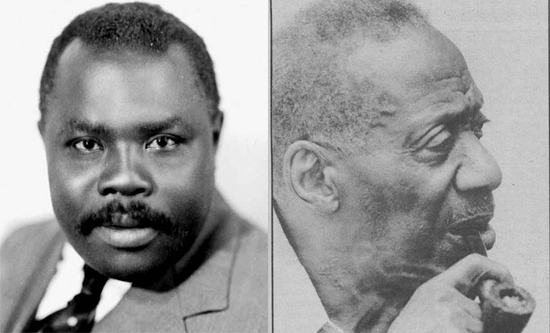

In the first part of this century, Marcus Garvey (left) built a powerful black organisation in the United States. Harry Haywood (right) of the Communist Party of the USA called Garvey’s UNIA the ‘first great nationalist movement’, but criticised its diversion ‘into reactionary separatist channels’. Today, the debate continues. Labour opportunists and black nationalists are promoting Garvey’s outlook as a guide for anti-racist action today. EDDIE ABRAHAMS and SUSAN DAVIDSON examine the communist standpoint on the heritage of Marcus Garvey.

1987 and 1988 were important anniversaries in the struggle for black liberation. In 1838 slavery was abolished in the British Caribbean colonies. In 1887 Marcus Garvey, an outstanding pioneer of black nationalism, was born in Jamaica on 17 August. These anniversaries were used by a variety of Labour Party opportunists and black nationalists to present Marcus Garvey’s political outlook and contribution as a valid guide for the struggle against racism and imperialism today.

Garvey dedicated his life to the fight for his people, ‘the mighty Negro race’ as he put it. He was a writer, publisher, newspaper editor, political organiser and agitator. To this day many claim to be following in his footsteps.

Within the communist and anti-racist movement there continues to be fierce debate about Garvey’s actual political outlook and its contribution to the struggle for black liberation and socialism. This debate dates back to the height of his influence when he was leading the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) – a truly popular movement based among the impoverished black masses in the USA during the post-World War One era.

Garvey’s ideas retain a resonance among sections of the petit-bourgeoisie and Labour Party engaged in the fight against racism today. Thus it is all the more necessary for communists to understand the significance and contradictory character of Garvey’s heritage.

Garvey – political organiser

In 1909, at the age of 22, already an accomplished journalist, Garvey left Jamaica for a tour which took him through Costa Rica, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Honduras, Colombia, Venezuela and Panama.

In all these countries he witnessed first hand the appalling poverty, suffering and exploitation of fellow Jamaicans forced to leave their homes in search of work and livelihood. In Panama he was particularly shocked by the conditions of workers constructing the Panama Canal.

As he travelled he lectured and harangued workers in the tobacco fields, the mines and factories attempting to organise them to improve their conditions.

He returned to Jamaica in 1914 where he took his first major step as a political organiser when he founded the UNIA. His travels had convinced him that the scattering of African people throughout the world at the mercy of white exploiters was the source of their weakness. The UNIA’s founding statement proclaimed that it aimed ‘To unite all Negro people in the world in one great body to establish a country and a government absolutely our own.’

Garvey was to extend his vision of black liberation to include the liberation of Africa which was then divided up among the major European imperialist powers. He adopted the slogan ‘Africa for the Africans – At Home and Abroad’.

Whilst the UNIA did not initially grow in Jamaica, it became a mass movement in the United States very rapidly after Garvey arrived there in 1916. This success led to an immediate clash with the then dominant organisation amongst black people – the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People). By 1919, the UNIA had over 30 branches in different cities and claimed a membership of over 2 million. Garvey’s newspaper, The Negro World, was printed in Spanish, French and English and had a large international distribution. In many colonies it was banned. Penalties for possession were usually five years. In French Dahomey it was life.

Garvey and the black working class

The UNIA that Garvey built in the USA represented a mass break-away of black people from the bourgeois NAACP. The rift between the bourgeois leadership of the NAACP and the actual conditions of poverty, unemployment and racism faced by the mass of black people after the first world war led the rising movement of black people to look elsewhere for leadership – they turned to Marcus Garvey and UNIA.

However, neither Garvey’s organisation nor politics were capable of dealing with the masses’ democratic and social demands. Black communist Harry Haywood spoke of this ‘first great nationalist movement’ being ‘diverted into reactionary separatist channels’ which: ‘under the generalship of Garvey . . . was diverted from a potentially anti-imperialist course into channels of “peaceful return to Africa” ‘.

In preparation for such a return to Africa, the UNIA held a conference in 1920 when 25,000 delegates packed Madison Square Gardens to discuss its practicalities. In an almost carnival atmosphere Garvey was proclaimed Provisional President of Africa to rule with the aid of a court of dukes and nobles created by the movement in the image of the European aristocracy.

Garvey enthusiastically sponsored the development of black capitalist enterprises. Profits from these were to finance the ‘return to Africa’. In 1919 the Black Star Shipping Line was established, followed the next year by a Negroes’ Factories Corporation which developed a chain of grocery stores, restaurants and laundries to be managed only by and for black people.

Whatever its idealistic intentions, this programme actually served the immediate needs of the black petit-bourgeosie in a period of economic crisis which had devastated the ghetto economy. Additionally the UNIA’s lack of democratic organisation prevented genuine representatives of the black working class, including communists, taking leadership positions in the movement.

Garvey, capitalism and communism

One reason for Garvey’s phenomenal, though passing, success was the inability of the newly formed Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA) to make central the question of racism and the leading role of the black working class in any communist movement in the USA. There were those within the CPUSA who even denied the existence of racism and viewed all matters only as ‘class’ issues. Thus they deliberately turned a blind eye to white chauvinism and the racism of the labour aristocracy. The revolutionary trend in the CPUSA were forever having to conduct fights against the racism of large sections of the Party membership. So in effect, the labour movement in the USA, and the CPUSA in particular, failed to unite with the emerging black working class, which therefore quite naturally supported non-communist, indeed anti-communist and black separatist forces such as Garvey’s UNIA.

While communists and Garveyites did on occasion make alliances in social struggles, they were more frequently engaged in bitterly hostile confrontations. As communists developed their work in black areas such as Harlem and began to have success in organising working class people, Garvey launched an openly anti-working class and anti-communist campaign.

Garvey opposed black and white workers organising together. While communists fought to organise and improve the conditions of all workers, black and white, Garvey was advising black workers to sign no-strike deals and to scab. He declared:

‘. . . the only convenient friend the Negro worker or labourer has in America at the present time is the white capitalist … If the Negro takes my advice he will organise by himself and always keep his scale of wage a little lower than the whites until he is able to become, through proper leadership, his own employer . . . ‘

In 1924, at the UNIA’s International Convention, Robert Minor, a communist, proposed an alliance between the UNIA and CPUSA to fight racism in the trade unions and together to declare war on the Ku Klux Klan. Garvey opposed these.

He didn’t merely oppose communists fighting anti-racism, he actively collaborated with the racists. He called communist attacks on the KKK an ‘act of political suicide’. It was in this same year that Garvey met Colonel Simmons, Imperial Grand Wizard of the KKK and invited John Powel, organiser of the Anglo-Saxon Clubs to address the UNIA. This criminal collaboration was undertaken in the belief that it could hasten the repatriation of black US citizens to Africa.

The UNIA which in its first period gave thousands upon thousands of black people a sense of dignity and confidence disintegrated rapidly because of Garvey’s petit bourgeois politics; his escapist programme of a ‘return to Africa’ was an obstacle to a militant fight for democratic rights in the USA. His separatism led him to say:

‘We are not organising to fight against or disrespect the Government of America.’

In the meantime, the example of the sheer determination of communists to fight on in campaigns ranging from ‘No Work, No Rent’ and anti-lynching demonstrations, fighting the police, risking arrest and imprisonment in daily activity won to their membership many who became disillusioned with Garvey’s schemes. However, the CPUSA failed to make the issue of black liberation central to its platform and gradually succumbed to the chauvinism of the USA labour movement. Thus, the CPUSA lost any support it did have among the black working class. It was left to a few isolated communists such as Harry Haywood, and later in the 70s, George Jackson, outside of the CPUSA, to develop the correct communist position which placed the black working class and the struggle against racism at the very centre of a revolutionary working class movement.

Despite Garvey’s petit-bourgeois politics, the US ruling class could not tolerate any significant black organisation with a mass base. The FBI therefore framed Garvey, jailed him for two years and then deported him to Jamaica in 1927. Until his death in 1940 in London, Garvey remained active in black politics but never with the same mass following he enjoyed in the USA.