Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! No 70 August 1987

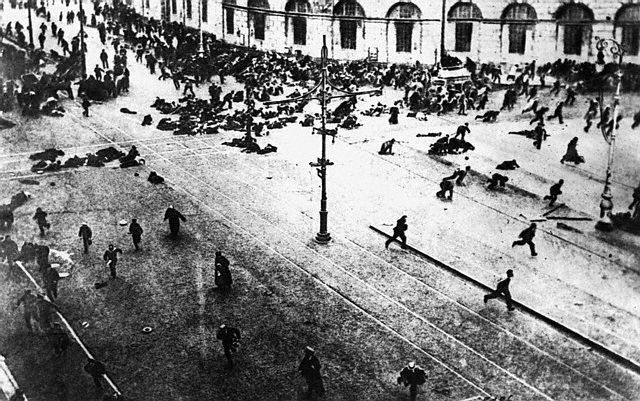

Nevsky Prospect 1917

The first trial of strength between the Provisional Government and the Soviets occurred over Foreign Minister Miliukov’s Note of 18 April, assuring the Allies that the Russian army could be relied on ‘ . . . to fight the world war out to a decisive victory.’

The Menshevik-SR bloc sought to give the Note a favourable ‘interpretation’, but the soldiers faced with a return to the front had little interest in such casuistry: Miliukov’s intentions were unambiguous enough. On 21 April the demonstration called by the Bolsheviks was strongly supported by workers from the Vyborg District and by armed soldiers. In the bourgeois districts the forces of the counter-revolution – the armed officers, the cadets and the gilded-youth – began to mobilise openly for the first time.

Civil war seemed imminent. But the masses immediately heeded the Soviet’s call not to hold further demonstrations. With the addition of a few anodyne phrases to Miliukov’s Note suggesting that the war was not for annexation or conquest, it considered the matter ‘settled’. The reassuring formulae of the rewritten Note were accepted in the Soviet by an overwhelming majority.

Yet the episode demonstrated the reality of the Soviet’s own statement to the people: ‘We alone have the right to give you orders’. With the masses, it was the Soviet and not the Provisional Government which held the power and the authority. But what should the Soviets do about the Provisional Government?

The government itself posed the question point-blank, on 26 April, appealing to the Menshevik-SR bloc to participate. After considerable vacillation, the lure of ministerial office proved too strong. On 1 May, the Soviet EC decided by 41 votes to 18, with only the Bolsheviks and a small group of left-Mensheviks against, to enter the government.

The First Coalition

The Menshevik-SR bloc had six ministries out of 16, including Agriculture, (Chernov, SR) Labour, (Skobelev, Menshevik) and War (Kerensky, Popular Socialist). Perhaps over-excited by their dizzy rise to ministerial eminence, they made some very rash promises indeed. Before he returned to the routine activities of a ‘socialist’ Minister of Labour – opposing strikes, asking the workers to exercise restraint – Skobelev threatened ‘We’ll take all the profits, we’ll take 100 percent’. In the eyes of the non-Bolshevik masses, the entrance of the Menshevik-SRs into the coalition seemed a step forward. Some of the ministers had a long and honourable record of anti-Tsarist activity. Tsereteli, who became leader of the bloc, had spent many years as a prison labour convict; and in 1916 both he and Chernov had been on the left wing of the anti-imperialist movement. Perhaps the socialist ministers would gradually crowd out the bourgeois ministers (Miliukov had been forced to resign on 2 May), leading to an all-socialist government which could grant their demands without further struggle.

The real significance of the coalition, as yet hidden from the masses, was contained in one clause of the new government’s Declaration: the need to prepare the army ‘… for defensive and offensive activity . . . ‘. The Allies badly needed a Russian offensive. By June half of the French army was considered unreliable, due to the influence of the Russian Revolution.

The bourgeoisie aimed to use the ‘socialists’ as agents to persuade the masses to continue the war. The British Ambassador, Buchanan wrote to the Foreign Office: ‘The Coalition Government . . . is for us the last, and almost the only hope for salvation of the military situation . . .’

The Rise of the Bolsheviks

But even before it began to prepare openly for an offensive, the coalition’s pro-bourgeois policies compromised them in the eyes of the masses, who began to turn to the Bolsheviks. The Bolsheviks had the greatest success in two places: the Petrograd factories and the Kronstadt naval base.

In the factories, the capitalists struck against the revolution by means of a lock-out. Between March and the end of July, with increasing momentum, 568 factories were closed down with the loss of 104,000 jobs. In the South Russian coalmines, the owners deliberately sabotaged and disorganised production.

The Bolsheviks’ solution was simple and straightforward: ‘Make the profits of the capitalists public, arrest fifty or a hundred of the biggest millionaires … for the simple purpose of making them reveal . . . the fraudulent practices which . . . are costing [Russia] thousands and millions every day.’ (Lenin CW 25 p 21).

The appeal of the Bolshevik slogans was shown at the first conference of Petrograd Factory Committees (30 May-3 June), when the Bolshevik resolution won 80% of the votes. The workers’ section in the Petrograd Soviet was already a Bolshevik majority; and in the Moscow Soviet the largest party, with 41% of the seats.

Kronstadt was the chief naval base, protecting the approaches to Petrograd. The 80,000 strong Baltic Fleet was an explosive combination of class forces: in 1917, 25.4% of the sailors were working class, and over 90% of the younger officers came from the nobility; and in the pre-1917 period discipline was so harsh that a rating remembered that the very name of the Governor General sounded ‘like the crack of a cossack’s whip’. From the beginning of May Kronstadt was dominated by the Bolsheviks – their refusal to enter the coalition meant they bore no responsibility for its increasingly unpopular policies.

But in Russia as a whole, the Bolsheviks were still very much a minority. At the first All Russia Congress of Soviets of Workers and Soldiers Deputies (3-24 June), the Bolsheviks (105 delegates) were still a long way behind the SRs (285) and Mensheviks (248); three quarters of the delegates were prepared to ratify the coalition.

The June Demonstration

While the Congress was in session, on 9 June, the Bolsheviks’ Military Organisation proposed a mass demonstration against an offensive, under two slogans: ‘All Power to the Soviets’, ‘Down with the ten capitalist ministers.’

The Congress passed a resolution forbidding demonstrations for three days, on the grounds that ‘concealed counter-revolutionaries want to take advantage of the demonstration’ which was ‘a Bolshevik conspiracy to overthrow the government and seize power’. Recognising the authority of the Congress, the Bolsheviks prevailed on their supporters to accept the decision.

Feeling, however, the need to demonstrate their supposed popularity, on 12 June the Menshevik-SR bloc authorised a demonstration for 18 June under their slogans – ‘Universal Peace’ ‘Immediate Convocation of a Constituent Assembly’ ‘Democratic Republic’ – not daring to demand support for coalition with the bourgeoisie or the renewal of the offensive. Its leader, Tsereteli, boasted: ‘Now we shall have an open and honest review of the revolutionary forces …’

True enough – about 400,000 workers and soldiers came out in an unarmed demonstration – but under the Bolshevik slogans: ‘Down with the offensive!’ ‘Down with the ten capitalist ministers’. Only 3 small groups carried banners bearing the slogan ‘Confidence to the Provisional Government’, until they were forced to lower them by the angry demonstrators. Demonstrations in the provincial towns showed the same picture, if less sharply drawn.

The Offensive

On 12 June the Congress of Soviets gave Kerensky approval to resume military operations. Only the Bolsheviks voted against. Launched on 18 June, at first it made considerable advances – but against empty trenches and undefended positions. When the Austrians made a stand, the Russian army went into headlong retreat, with commanders at the front reporting mass desertions and collective refusals to obey orders.

The Bolsheviks were the only party to oppose the offensive in advance: a resolution of greeting to the advancing army at the Petrograd Soviet had a substantial majority (40%) against.

At the end of June, therefore, the problem faced by the Bolsheviks was not that of gaining support – it was how to restrain the masses from rushing into a premature insurrection. Already on 21 April, sections of the Bolsheviks had come out with the premature slogan ‘Down with the Provisional Government’; on 17 May the Kronstadt Soviet passed a resolution supported by the Bolsheviks declaring itself to be the sole authority.

Lenin’s speech at the All-Russian Conference of Bolshevik Military Organisations (20 June) warned: ‘One wrong move on our part can wreck everything … If we were now able to seize power, it is naive to think that having taken it we would be able to hold it … we are an insignificant minority . . . the majority of the masses are wavering but still believe the SRs and Mensheviks.’ (A Rabinowitch Prelude to Revolution 1968 p 121-122). The test was soon to come: the ‘July Days’.

3 July

As the offensive fails Kerensky gives orders for regiments from Petrograd to be sent to the front. Stormy protests from the garrison soldiers, led by the 1st Machine Gun Regiment, calling for an armed demonstration. Its only Bolshevik officer, who may in fact have been a provocateur, does not attempt to hold the soldiers back. Delegates from the regiment arrive at Kronstadt at 2pm to appeal to the sailors for support. The Bolsheviks’ most popular speaker, Sernyon Roshal, is shouted down when he tries to restrain the crowd.

Other delegates go round the Petrograd factories and by 7pm all are out on strike. They have less success with the soldiers – at this point only a few isolated regiments are definitely pro-Bolshevik. The supporters of the Provisional Government spend the day frantically rushing round Petrograd in a search for loyal troops, but can only find 100 men.

4 July

20,000 armed Kronstadters set off for Petrograd. They march to the Bolshevik HQ in Kseshinskaya’s Palace, where they are greeted by Lenin. He calls for All Power to the Soviets, and appeals for firmness, steadfastness and vigilance.

From there they march along the Nevsky Prospect, the Petrograd equivalent of Bond Street. As the Kronstadters reach a street junction, provocateurs fire from the windows and attics of the houses at the rearguard of the demonstration. Panic! Rifles fire into the air, at the ground, marchers scatter and disperse, reforming only when the invisible enemy is silenced.

There is only one, quite small-scale pitched battle between revolutionaries and their opponents. Cossacks open fire upon workers and machine gunners – on both sides 13 are killed, and 32 wounded. In all the skirmishes and random shootings, 56 people are killed and 350 wounded (contemporary estimates).

The marchers approach Tauride Palace, home of the Petrograd Soviet. Peasant sailors seize Chernov, demanding a re-distribution of the land. A worker shakes his fist in his face: ‘Take the power, you son of a bitch, when they give it to you.’ He may be killed on the spot – but with Trotsky’s help, the crowd calms down and he is freed.

This is an elemental popular movement surging out of party control. But there is no attempt to make an insurrection, by seizing the key centres of power (railway stations, post office, banks etc). As the Chernov incident shows, the demonstrators wanted Soviet power, were opposed to the Soviet leadership but not yet strong enough to overthrow that leadership.

5 July

The tide begins to turn against the revolutionaries. At 2am the offices of Pravda are sacked by an unruly mob of officers and students. Two hours later, the 3 most backward guard battalions arrive at the Tauride to defend the Soviet against the Bolsheviks. At their head is the Izmailovsky Regiment, instrumental in destroying the Petrograd Soviet in 1905.

How has the Menshevik-SR bloc managed to find loyal troops? From the previous afternoon, the rumour has been spread that Lenin is a German spy. The first morning editions of the bourgeois press duly oblige. A wretched Black Hundred rag, The Living Word carries the banner headline: ‘Lenin is a German spy!’ An official fabrication written by two notorious scandalmongers, it is based on the ‘evidence’ of a former police agent and a speculator.

At 7.45am the 300 sailors and 200 machine gunners in Kseshinskaya’s Palace are ordered to lay down their arms. They retreat to the Peter-Paul Fortress, but agree to leave with their arms. The Menshevik conducting the negotiations (Lieber) is still unsure of his ground. But as increasing numbers of loyal troops arrive, Lieber grows more and more vengeful and insists that the Bolsheviks leave unarmed.

6 July

Cossacks and other reactionary regiments, containing pro-Tsarist and Black Hundred supporters, arrive from the front. At last the Menshevik-SR bloc has found enough loyal supporters to prevent any further demonstrations. Pravda and Soldiers Pravda are suppressed, party organisations driven out of their premises and forced to go underground.

In Lenin’s view, this was ‘something considerably more than a demonstration and less than a revolution.’ But is this a definitive victory for the counter-revolutionaries? Will they seize the opportunity to destroy the Bolsheviks? Or are the inner forces of the revolution strong enough to overcome this setback?

PATRICK NEWMAN