In Lenin’s eulogy after the death of Frederick Engels in 1895, he wrote: ‘What a torch of reason ceased to burn! What a heart has ceased to beat!’ Lenin considered Engels ‘one of the two great teachers of the modern proletariat’. Marx and Engels, he said, were the first to formulate the theory of scientific socialism as a weapon for the working class. Engels’ lifelong correspondence and collaboration with Marx provided the spark for some of the greatest works of socialist theory that communists rely on today: in 1867, on finally checking off the last proof of Capital, Marx wrote to Engels: ‘Dear Fred… This volume is finished. I owe it to you alone that it was possible’. Engels’ own writings encompassed everything from military theory to anti-colonial struggles, housing, religion, ecology and women’s oppression. 200 years after his birth, they remain as resonant as ever.

Early days

Engels was born on 28 November 1820 in the Prussian Rhineland town of Barmen, to a wealthy industrialist family. It was a turbulent time: across Europe the bourgeoisie was challenging the old feudal order – economically, politically and intellectually – opening the way for the rapid development of capitalism. From an early age, Engels engaged with the democratic and progressive movement emerging in Germany. Aged just 19, he wrote Letters to Wuppertal, castigating the hypocrisy of industrialists in the Rhineland region as a whole and in his hometown in particular. Like Marx, he joined the radical Young Hegelians, but was rapidly disillusioned with their petit-bourgeois ideology and lack of practical engagement in the struggles of the day. However, the ideas of Hegel provided revolutionary material for Marx and Engels, with his faith in human reason and his dialectical understanding of the processes of constant change. But, rejecting the Hegelian principle that everything emanates from ‘The Idea’, Marx and Engels turned idealism on its head. They understood that ‘the idea’, the mind, must be explained by nature – matter.

In 1843, Engels travelled to England to work at a factory part-owned by his family. He witnessed at close hand the lives of the working class in the great industrial centres of London and Manchester, resulting in his magnificent 1845 indictment of capitalism – The condition of the working class in England. Engels was not the first to chronicle the grinding poverty of the industrial working class – and in particular of Irish migrants – but he was the first to explain it as a necessary and logical consequence of the rapid development of British capitalism that must inevitably drive the working class to fight for emancipation.

A great collaboration begins

In England, Engels established contact with the British labour movement and began to write for socialist publications. Having met Marx in Paris in 1844, the two began to correspond, eventually on an almost daily basis, exchanging ideas and working together on publications. They wanted to produce a materialist, proletarian world outlook to assist the working class in its historic mission of self-emancipation. Their first collaboration, in 1845, was The Holy Family, in which they comprehensively rejected idealist philosophy, laying out the foundations of revolutionary materialist socialism. In 1846 came The German Ideology, articulating the basic principles of historical materialism.

Between 1845 and 1847, Engels spent time in Brussels, Cologne and Paris. Across Europe anti-feudal and potentially revolutionary struggles were emerging, culminating in the European bourgeois revolutions of 1848. In Cologne, Marx and Engels set up a newspaper, Neue Rheinische Zeitung, whose offices became the de facto headquarters of communist activity in Germany. Engels also supported the Hungarian independence movement, which waged a ‘people’s war’ against the Austro-Russian armies. Engels fought at Rastatt fortress with the Prussian communist August Willich’s doomed corps of 800 workers and soldiers. These military exploits led him to formulate basic concepts of Marxist theory of war in works such as Po and Rhine 1859, Savoy, Nice and Rhine 1860 and The American Civil War 1861, examining the dependence of military form on political-economic essence, the organic link between geopolitics and class struggle, the tendency towards technological sophistication and obsolescence under capitalism.

In 1848, fired up by the events in Europe, Marx and Engels published The Communist Manifesto. In Lenin’s words, ‘to this day, its spirit inspires and guides the entire organised and fighting proletariat of the civilised world’. The Manifesto, the second most published book in the world, concludes with a call for the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions: ‘The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win.’

The working class in Britain and Ireland

The engagement of both Marx and Engels with the working class movement in Britain in the following decades led to their major contribution in showing how that movement became weakened by the opportunist currents that emerged in the major capitalist countries. Their analysis of this process in Britain – the most advanced capitalist country at the time – particularly in relation to its oldest colony, Ireland, would lay the groundwork for a key feature of Lenin’s work on imperialism, the split in the working class. Marx and Engels traced the connection between the imperialist features of British capitalism – most notably its vast colonial possessions and a monopoly position in the world market – and the emergence of an opportunist political trend amongst the working class (see FRFI 27, March 1983). Much of this analysis resulted from their work with the National Chartist Movement. Founded in 1840, the Chartists were a mass militant working class movement that had emerged from the struggle for the ten-hour working day and against the New Poor Laws. They demanded universal male suffrage and, drawing in the support of hundreds of thousands of working class people, for a brief period appeared powerful enough to threaten insurrection. But after the March 1848 débacle at Kennington Common, when the movement’s revolutionary potential was defused by the abject capitulation of opportunist elements, the movement was divided and went into decline. Marx and Engels analysed the material reasons for this defeat, understanding it in the context of an expanding British empire that was able to offer a significant section of the working class, particularly skilled craftsmen, better wages, more secure employment and better working conditions. Such workers were now looking to make an alliance with liberal sections of the bourgeoisie, not overthrow it. As Engels put it in 1858:

‘The English proletariat is actually becoming more and more bourgeois, so that this most bourgeois of all nations is apparently aiming ultimately at the possession of a bourgeois aristocracy and a bourgeois proletariat alongside the bourgeoisie. For a nation which exploits the whole world this is of course to some extent justifiable’.

It was against this background that Marx and Engels were to revise their position on the relationship between the British and Irish revolutions.* Before 1848, they had argued that the Irish colony would be liberated through the struggle of the advanced proletariat in England. By 1869, Marx wrote that, on the contrary, ‘the English working class will never accomplish anything until it has got rid of Ireland. The lever must be applied in Ireland.’ Ireland, he concluded, was the key to the British revolution. Several material factors led to this important revision. Engels made his first visit to Ireland in 1856, in the company of his partner, the working class Irish nationalist Mary Burns. He found a country where the peasantry lived in the most appalling poverty, serving a country run essentially by a parasitical layer of squires, priests, gendarmes and lawyers. There was no industrialisation of any kind. Where previously Marx and Engels had seen colonisation as speeding up productive relations in the colonised country and developing the working class, now they concluded that in fact it deliberately held back development. Ireland was little other than a source of cheap food and wool for the British colonialist – a point of unity for the ruling class. Meanwhile, the dispossessed Irish peasants were forced to migrate to England, providing a source of cheap labour, living in squalid conditions and enriching the bourgeoisie while dividing the working class. The fading of the revolutionary impetus within the working class movement in England, and the rise of revolutionary Fenianism in Ireland – which combined an armed national liberation struggle against colonialism with the struggle against the eviction of peasants from their land – cemented their understanding that the locus for revolutionary struggle was in Ireland, not England. These forces had, Engels wrote, nothing to lose, ‘two-thirds of them not having a shirt on their backs, they are real proletarians and sans culottes… Give me 200,000 Irishmen and I could overthrow the entire British monarchy.’ These experiences also led Engels to advocate a worker-peasant alliance as necessary for the advance towards socialism (The Peasant War in Germany 1850, The Peasant Question in France and Germany, 1894). This position – adopted by the Russian Bolsheviks in 1917 – broke with the stance common among socialists that the peasantry was a reactionary class force.

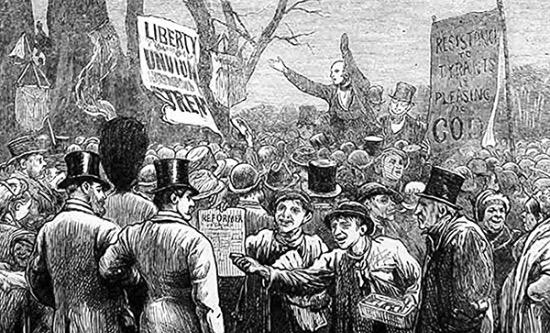

Through the First International, Marx and Engels worked tirelessly to draw the working class in England into solidarity with the Irish struggle, helping organise mass protests and rallies. But the split in the working class in the capitalist country was becoming ever more evident. As Engels observed, ‘The masses are for the Irish. The organisations and Labour aristocracy in general follow Gladstone [the prime minister] and the liberal bourgeoisie’.

After Marx

After the death of Marx – ‘the best, the truest friend’ – in 1883, Engels’ major task was to edit and prepare the volumes of Capital II and III that had not been published during Marx’s lifetime, in and of itself a huge contribution to socialist theory. He also produced a vast tranche of works in his own right, examining historical and social developments from a materialist perspective and applying the economic theories of Marx. In Anti-Duhring, Engels reiterated the basic principles of dialectical materialism; he went on to apply these principles to the natural sciences in Dialectics of Nature, with its visionary analysis that foreshadows contemporary environmental struggles. We should not, he wrote, gloat about the human conquest over nature:

‘For each such conquest takes its revenge on us. Each of them, it is true, has in the first place the consequences on which we counted, but in the second and third places it has quite different, unforeseen effects which only too often cancel out the first. The people who, in Mesopotamia, Greece, Asia Minor and elsewhere, destroyed the forests to obtain cultivable land, never dreamed that they were laying the basis for the present devastated condition of these countries, by removing along with the forests the collecting centres and reservoirs of moisture.’

In Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, Engels locates the emergence of private property as the catalyst for the ‘world-historic defeat of the female sex’, providing a solid materialist foundation for the particular character of women’s oppression under capitalism. Meanwhile, The Housing Question remains an increasingly relevant handbook for anyone analysing the disaster that is the provision of working class housing 150 years on.

In 1895, Engels was diagnosed with aggressive throat cancer. He died on 5 August of that year.

Throughout his life Engels provided a clear, succinct materialist analysis of the world around him.

He threw himself vigorously into political activity, arguing that theory must be tied to action to be relevant. He was generous to a fault, financially supporting Marx’s family throughout his life; a bon viveur who liked drink and the company of women; an intellectual with, in Marx’s words ‘a mind like an Encyclopaedia’ who could write prolifically whether drunk or sober. Marx always disputed Engels’ claim that he played ‘second fiddle’ to Marx during his lifetime; on the contrary, Marx wrote to him: ‘First, I’m always late off the mark with everything, and second, I inevitably follow in your footsteps’. Two hundred years after his death, Frederick Engels remains one of ‘the great teachers of the working class’.

Justin Theodra and Cat Wiener

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! 280 February/March 2021

See FRFI 7, November/December 1980 or https://tinyurl.com/yyy5bfu5 on our website.