A new path for socialism? Revolutionary renewal in the Soviet Union and Cuba – from

FRFI 82, November/December 1988

Recent issues of Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! have dealt with the debate on the transition to socialism. This debate so far has been dominated by the dramatic changes underway in the Soviet Union under perestroika and glasnost. Capitalist ideologists have seen in the Soviet reforms a vindication of capitalist principles and social norms. The left in Britain, politically and ideologically retreating before Thatcherism, has been unable and unwilling to attempt a serious defence of Marxism-Leninism. Cuba has been engaged in a process of ‘rectification’ since 1986. This has provided Fidel Castro with the material for assessing the transition to socialism in a third world country. His analysis, however, has produced conclusions that have a more general validity. They represent a major defence of Marxism-Leninism in the face of the systematic retreat widespread in the communist movement today. That is why so far his ideas have either been ridiculed or ignored in Britain. Here we reprint extracts from Castro’s speeches with a commentary.

No Two Revolutions are the Same

Fidel Castro makes it clear that measures Cuba is taking to resolve its problems are different from those adopted by the Soviet Union. This, however, does not mean, as bourgeois commentators have suggested, that there are problems in Cuban-Soviet relations, only that the difficulties the socialist countries are facing have different historical roots and, therefore, require different solutions (Granma 28 August 1988 p3).

‘There are some people who believe that what’s being done in other places is what we ought to start doing right away . . . That’s an incorrect stand, a wrong stand, because no two revolutionary processes are the same, no two countries are the same, no two histories are the same, no two idiosyncracies are the same. Some have certain problems, others have other problems; some make certain mistakes, others make other mistakes.

‘If someone has a toothache, why would he use a cure for corns? Or if his corns hurt, why must he use a cure for a toothache? That’s why our measures are not the same, nor can they be the same as those used by other countries and it would be entirely wrong for us to look for the same solutions or mechanically copy the other countries’ solutions.

‘Our Revolution and this no one can deny – has been kept going with tremendous ideological strength because who can defend us? Were imperialism to attack us, who is there to defend the island? No one will come from abroad to defend our island; we defend the island ourselves. It isn’t that someone might not want to defend us, the thing is that no one can because this socialist revolution is not just a few kilometres away from the Soviet Union; this socialist revolution is 10,000 kilometres away from the Soviet Union . . .

‘I believe that our country has carried out an extraordinary historical feat on building socialism in the geographical conditions in which it has done so and that’s why we must watch over the ideological purity of the Revolution, the ideological solidity of the Revolution. That’s why we can’t use mechanisms, any kind of tools smacking of capitalism; this is an essential question of the Revolution’s survival, that’s why the Revolution must resolutely stick to the purest principles of Marxism-Leninism and Marti’s thought, stick to them rather than playing around or flirting with the things of capitalism.’ (Granma 7 August 1988 p4)

Cuba Rejects Styles and Methods of Capitalism

‘What I can indeed tell the imperialists and the theoreticians of imperialism is that Cuba will never adopt methods, styles, philosophies or characteristics of capitalism. That I can indeed tell them! Capitalism has had some technologic-al successes, some successes in organisational experiences that can be used, but nothing more! Socialism and capitalism are diametrically different, by definition, by essence’ (ibid p5).

Cuba began its rectification process in response to the consequences of the economic reforms introduced from the mid-1960s onwards. In a speech to the Third Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba in 1986 Castro pointed out some of the consequences of giving cooperatives and state enterprises freedom to set prices and trade with other enterprises. These are measures presently being introduced in the Soviet Union.

He gave examples of ‘enterprises that sold their material and charged the prices of finished jobs, be it paint, lumber, asbestos tiles or anything else, to cite a few examples for there are a ton of them. Enterprises that tried to become profitable by theft, swindles, swindling one another. What kind of socialism were we going to build along those lines? What kind of ideology was that? And I want to know whether these methods weren’t leading us to a system worse than capitalism, instead of leading us toward socialism and communism. That almost universal chaos in which anyone grabbed anything he could, whether it be a crane or a truck. These things were becoming habitual and generalised . . .

‘The peasants were also getting corrupted. We no longer knew if a cooperative was an agricultural production cooperative, an industrial cooperative, a commercial cooperative or a middlemen’s cooperative. We were losing our sense of order: the trading between the cooperatives and state enterprises, state enterprises exchanging products, materials, food stuffs among themselves . . . a factory exchanging products with a farm, because while it sent the agricultural cooperative cement sweepings, the agricultural enterprise sent salted meat and who knows what else to the cement factory.’ (Granma 14 December 1986 p11)

If this process was generalised, as Castro pointed out, social provision to the population as a whole would come under threat.

‘If everyone started to do that, if that proliferated, nothing would be left. There wouldn’t be any meat for the schools, for the hospitals, for what has to be distributed to the population every day, every week, every month. If this kind of generalised trading developed among the state enterprises or between the agricultural production cooperatives and state enterprises, no one knows where this would all end, in what kind of chaos and anarchy. These are evidently negative tendencies, extremely evident!’ (ibid).

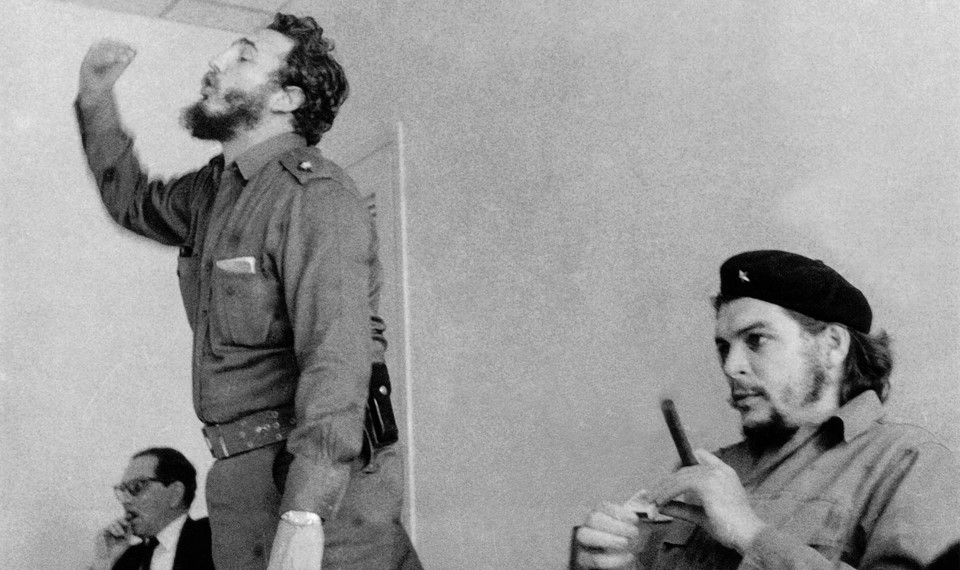

Castro’s essential point is that you cannot solve the problems of socialist construction using capitalist economic laws and methods. In a speech on the 20th anniversary of Che Guevara’s death Castro stated:

‘In essence – in essence! – Che was radically opposed to using and developing capitalist economic laws and categories in building socialism. He advocated something which I have often insisted on; building socialism and communism is not just a matter of producing and distributing wealth but is also a matter of education and of awareness. He was firmly opposed to using these categories which have been transferred from capitalism to socialism as instruments to build the new society.’ (Granma 18 October, 1987 p5)

Castro argues that they had thought that the problems of material production and the country’s development could be resolved by grafting capitalist methods onto the socialist system.

‘Apparently, we thought that by dressing a person up as a capitalist we were going to achieve efficient production in the factory and so after a fashion we started to play at being capitalists. Because it is only under socialism that you could dress up an administrator as a capitalist; if you wanted to make a capitalist out of him, you’d have to make him the owner of the factory and nothing else, return to the capitalist system. However you cannot achieve capitalist efficiency by making your administrators behave as though they were capitalists.

‘Capitalists take better care of their factories and better care of their money: they are always competing with other capitalists. If they turn out trash no one will buy it, and if they are not profitable they go bankrupt, they’re sued and deprived of their property; they lose their jobs as administrators and stop being the owners.

‘Our man dressed up as a capitalist produced anything and forgot about quality: if he had to produce 1,000 items, he did; he didn’t solve the contradiction between quantity and quality nor did he keep good checks on quality, nor did he care about it, he just cared about fulfilling his production plan. He began to sell at higher prices, he began to steal to have the factory be profitable, and in the end he didn’t even care whether the enterprise or factory was profitable, for the state would come forward at the end of the year and shoulder the deficit. What were the problems facing our man dressed up as a capitalist? He could spend his entire life playing the role of a capitalist without achieving efficiency or else making shady deals and being paternalistic, solving individual people’s problems here and there.’ (Granma 14 December 1986 p12)

Castro was not opposing the idea of enterprise profitability or cost accounting but rather the methods used to try and achieve economic efficiency.

‘Our man dressed up as a capitalist could not solve these problems because it isn’t capitalism or the capitalist methods that under the conditions of socialism can bring about efficiency in an enterprise. This doesn’t mean we’re giving up these mechanisms, no! We shouldn’t give up the system of paying salaries according to the amount produced in the field of material production since it is impossible to do so in other fields – I’ve mentioned this before – it would be absurd. We can’t give up paying salaries according to amount produced, work norms or the socialist formula of getting paid according to quantity and quality of work, quantity and quality! We shouldn’t give up the idea of enterprise profitablity or cost accounting. I’m not against any of those mechanisms or categories, provided we fully understand what political work, revolutionary work is, the sense of responsibility instilled in cadres, the sense of responsibility of cadres, what can make efficiency possible, not dressing up our administrative cadres in the material production sphere as capitalists.’ (ibid pp12-13).

Capitalist competition has to be replaced by a communist sense of responsibility. There is no other way.

‘When there is no competition, if the motivation prompting the owner in a capitalist society to defend his personal interests is out of the question, what is there to substitute for this? Only the cadres’, individual people’s sense of responsibility, the role played by the cadres. The man who is in charge there must be a Communist. It is unquestionable that being a member of the Party, or not being one, the man who is in charge there must be a responsible man, must truly be a Communist, a Communist! A revolutionary. And not a communist playing at capitalism, a Communist dressed up as a capitalist or, mark you, a capitalist dressed up as a Communist.’ (ibid p13)

The Critical Role of the Party

Castro argues that in the rectification process the role of the party, far from being weakened, has to be strengthened.

‘Without the party no construction of socialism is possible.

‘And we must say here, once and for all, that we need just one party, in the same way that Marti needed just one party to wage the war for Cuban independence, in the same way that Lenin needed just one party to make the October Revolution. I say this to stop the wishful thinking of those who believe that we’re going to start allowing pocket-sized parties, to organise perhaps the counter-revolutionaries, the pro-Yankees, the bourgeoisie? No! There’s only one party here, and that is the party of our proletarians, our peasants, our students, our workers, our solidly and indestructibly united people. That’s the one we have and will have!

‘We don’t need capitalist political formulas, they’re just trash, they’re good for nothing, what with their incessant political scheming. I was telling you how a voting card was demanded to get medical attention; none of these phenomena exist here now. We created our own political way to suit the country, we have not copied it, these are our own political ways to organise people’s power.

‘As you know – because that’s the practice among you – the candidates to delegates for the circumscriptions (electoral districts) are not proposed by the Party, they are proposed by the people gathered in free assemblies in the circumscriptions and they select the best in their opinion; they can choose up to eight candidates and a minimum of two, and if one of them doesn’t get 50 per cent, a new round of voting must start. You don’t have to tell me – I haven’t been able to escape even once from that second round of voting in the elections in my own circumscription. We all know that and we know that the Party doesn’t finger anyone or propose anyone, it’s the people who do it. It is those circumscription delegates who make up the Municipal Assembly, the ones who set up and constitute the Provincial Assemblies. Those delegates of the people, nominated by the people and elected by the people are the ones who make up the National Assembly of People’s Power.

‘We have to rectify absolutely none of this, ours is a superdemocratic system, more democratic than all the bourgeois systems of the millionaires, the plutocracy, the real rulers, generally speaking, of the capitalist countries.

‘We have nothing to learn from them and we will not stray one iota from this road, where power emanates from the people. And you all know how our Party emerged from the people, it didn’t drop from heaven, and how our Party members are chosen among the best in the youth and among the best workers. That was also an innovation, something absolutely new in the way of creating and expanding the Party and that is very much present in the history of our Party which always subjected the admission into its ranks to the will of the masses, the opinion of the masses, the support of the masses. That’s why our Party stands so close to the masses.

‘I know that outside the Party there are millions of extraordinary men and women and communists, we’re a people of revolutionaries, yet the Party must be made up of a selection of them and it can’t be otherwise because they must be a vanguard. And you know very well what it means to be a member of the Party: he or she must be the first in everything when there’s a difficult job, an internationalist mission, a sacrifice to be tackled, a risk to be taken; there the first turn, the first possibility goes to the Party member. It’s not a party of privileged people but a Party stemming from the midst of the people, whose members must set an example and when they don’t set an example the Party sees to it that they are expelled from its ranks.

‘In this rectification process the Party will have increasing strength because, I repeat, socialism can’t be built without the Party. Without the Party capitalism, which stands for chaos, can be built, it doesn’t need anyone to organise it, it is self-organised with all its rubbish. Socialism is not created by spontaneous generation, socialism must be built and the basic builder is the Party.’ (Granma 7 August 1988 p5)

Socialism in The Third World

During the course of the debate on the transition to socialism some in the communist movement have resurrected the Menshevik argument that socialism cannot be constructed in the less developed countries. Castro totally rejects this view.

‘One of Lenin’s great historical merits was to have thought of the possibility that socialism could be built even in an industrially backward country. (Granma 14 December 1986 p12)

‘For a Third World country a prerequisite for this construction is hard work and efficient use of available resources.

‘Perhaps one of the tragedies of the Third World countries is that they long for the level of consumption of the developed capitalist countries, working seven, six or five hours. It is a dream, an illusion. If we want a lot of material well-being, the degree we need and want, we must work and work hard, we must increase labour productivity, we must make rational use of all human and material resources; there is no other way’ (Granma 7 August 1988 p3).

Socialist construction requires a rejection of the capitalist model of development and consumerism. In the case of Cuba the problems of obtaining hard currency to pay foreign debts and buy advanced machinery demand a reduction of imports and increase in exports. This will require sacrificing luxury consumption even when made available to foreign tourists.

‘That’s why we must develop exports in every possible branch and exploit two marvellous resources of the country, the sun and the sea. That’s why we must develop tourism and are making a special effort in this field. There is a great international demand for tourist accommodations in Cuba and you know about the wonders of our coast and nature. There is Baconao Park, for example; there you can see what’s been done in a short time with limited means, and there are three international hotels in Baconao bringing in hard currency.

‘Some people will say: “It’s too bad that I can’t go to such and such hotel”, but we can’t have everything. We can’t have waterworks, schools, hospitals, health, food, transportation, everything, and in addition enjoy all the hotels. We have no choice but to export hotel services and deprive ourselves of some hotels; although often those hotels during part of the year when there is no international tourism, especially in the hot months, will provide service for Cubans, except in the case of joint enterprises where that would mean a loss of hard currency for the country.

‘I say this because there are people who react unrealistically. I have heard petit bourgeois, genuinely petit bourgeois views, from people who want to have the university, hospital, school, career, job, transportation, recreation, art, culture, everything! They say: “It really bothers me that in my country I can’t go to such and such a hotel” which of course they view as a tragedy and the fault of the Revolution. We could also say, “It’s too bad we can’t consume all the lobster we produce”! We produce more than 10,000 tons of lobster and we must export it to rich Japanese, to rich Spaniards, to rich Canadians, so they can eat lobster while we go without. It is very tasty, no one doubts, and it is served in some restaurants.

‘There may be no lobster, but the price of a ton of lobster in the world market enables us to buy 20 tons of powdered milk and with those 20 tons we produce 200,000 litres of milk and those 200,000 litres provide milk all year round for many children in the mountains, many who never had milk before, many who were formerly undernourished. We can say there is no lobster on the Cuban menu but there are no children begging in the streets. There is no lobster but there are no undernourished or starving children in our country, all children get a litre of milk daily, which is why we have one of the healthiest people in the world.’ (ibid p4)

Socialism and Agrarian Reform

The land question was dealt with in Cuba in a very different way to other socialist countries.

‘The manner in which an agrarian reform was carried out in our country differed from the manner in which all the other socialist countries carried it out, because they all divided up the land and we didn’t. Had we divided up the big cattle ranches or the sugar plantations in small lots or tiny parcels, today we wouldn’t be supplying calories for 40 million people. We kept those land units intact and developed them as big production enterprises. We gave land to the peasant who was in possession of it, to the sharecroppers, tenant farmers and others. We said to them all, here you are, the land is yours, and subsequently we haven’t forced any of them to join co-operatives. The process of uniting these plots has taken us 30 years, we’ve gone ahead little by little on the basis of the strict principle of it being voluntary. There can’t be a single peasant in Cuba who can say that he was forced to join a co-operative, there can’t be any! And yet, over two-thirds of their land now belongs to co-operatives, and all of them are making headway, they are prospering. On the other hand, 80 per cent of the land in our country belongs to state farms whose self-sufficiency is collective. The co-operatives are also self-sufficient. It was a different road they took.’ (ibid)

Socialism and Planning

In Britain the whole concept of planned production is under attack even from the ranks of so-called socialists and Marxists. They point to recent developments in the Soviet Union as vindication for their rejection of the fundamental tenet of Marx’s conception of the socialist economy. Castro goes against this stream and links the strengthening of the party with the role of the plan.

‘Another essential point in our rectification process: we will not weaken the role of our plans or the role of our development programs. We are convinced and are very aware of the importance of planning our development, of how important our plans are; our main problem is to draw them up well. But not only that, we must avoid turning the plans into strait-jackets. That’s why, while we must make sure that we are capable of planning well, we must also create the necessary conditions to cope with new problems, new situations and new possibilities.’

Internationalism

The Cuban people led by the Communist Party have demonstrated their commitment to the principles of internationalism, which are regarded as central to their own revolutionary ideology.

‘We’re proud of the ideological purity, of the ideological strength of a country that has confronted imperialism; and not just confronted imperialism but a country where hundreds of thousands of its people have fulfilled internationalist missions, a country where one only has to raise his hand and if 10,000 teachers are needed for Nicaragua, all 10,000 teachers turn up and go to Nicaragua; if doctors are needed, doctors go there; a country that when fighters were needed has always had ten times more fighters willing to fulfill the mission than the number of fighters actually needed.’ (ibid)

This internationalism has most recently changed the balance of forces against imperialism and apartheid in Angola.

Castro reaffirms the historic mission of socialism in its superiority over all other previous social forms.

‘It is a question of solving and confronting new problems stemming from our progress, our development and the great historical challenges of developing the country, building socialism, advancing along the road to communism, developing revolutionary theory and practice, demonstrating that socialism is not just overwhelmingly superior to capitalism in the fields of education, health care or sports, or other things where they admit we have shown progress, but also demonstrating to the capitalists what we socialists, we Communists, are capable of doing with pride, honour, principles and consciousness; that we are not once, not twice, but ten times more capable than they of solving the problems posed by the development of a country! It is a question of demonstrating that we are more capable than they are of being efficient in material production! It is a question of demonstrating that a consciousness, a communist spirit, a revolutionary will and vocation were, are and will always be a thousand times more powerful than money!’