Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! 92 January 1990

From the earliest stage of the proletarian struggle, the working class recognised the necessity of forging links with other sections of the working class internationally. Confronted with the internationalisation of capital, internationalism is the condition for working class and socialist advance. Karl Marx and Frederick Engels devoted an enormous amount of their time and theoretical talent to securing the development of an international working class organisation based on scientific socialism. In a three-part article, DAVID REED examines the history and politics of the first successful international organisation – The International Workingmen’s Association – The First International.

The general principles of Communism are laid down by Marx and Engels in the Communist Manifesto (1848) – the manifesto of the Communist League. They are as valid today as when they were first written. They broadly state that:

1. The capitalist system of production itself becomes a fetter on the further development of the productive forces and makes inevitable the replacement of capitalism by communism.

2. The capitalist system not only `forges the weapons that bring death to itself’, but has brought into existence the modern working class which is to wield those weapons.

3. The working class can only transform capitalist into communist society by ‘raising itself to the position of ruling class’ (establishing the dictatorship of the proletariat) and using its state power to expropriate the owners of capital – the old ruling class. After the experience of the Paris Commune in 1871, ‘where the proletariat for the first time held political power for two whole months’, an important addition was made. The Commune conclusively proved that ‘the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes’ (1872 Preface). It had to destroy the old state machine.

4. The ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ only constitutes the transition to the abolition of all classes and to a classless society. However, the ‘practical application of the principles’ would depend ‘everywhere and at all times’ on the existing historical conditions. For that reason, as Marx and Engels made clear, no special stress was to be laid on the practical measures at the end of Section II of the Manifesto.

Not only would the practical measures taken be ‘different in different countries’ but over time the ‘interests of the working class as a whole’ would require different tactical and programmatic positions to be adopted. On the international level these differences had to be argued over and clarified in the international movement over a period of 60 years before a Communist International was finally established. Many initial conceptions of the development of the revolutionary process internationally had to be changed as the real political process unfolded.

Communists, the Manifesto states, represent the interests of the working class as a whole. ‘The Communists are distinguished from the other working-class parties by this only: 1. In the national struggles of the proletarians of the different countries, they point out and bring to the front the common interests of the entire proletariat, independently of all nationality. 2. In the various stages of development which the struggle of the working class against the bourgeoisie has to pass through, they always and everywhere represent the interests of the movement as a whole.’

The working class of each country has to first of all settle with its own ruling class: ‘Though not in substance, yet in form, the struggle of the proletariat with the bourgeoisie is at first a national struggle.’

The working class must first of all acquire political supremacy, ‘must rise to be the leading class of the nation, must constitute itself the nation’ and in this respect it is ‘so far national though not in the bourgeois sense of the word’. The socialist revolution presented both a ‘national’ and international problem: how to win political power in a particular capitalist country, and how to integrate this struggle with other ‘national’ struggles to create socialism – a necessary precondition for the consolidation of the socialist revolution in any country of the world. The substance of working class struggle – how communists ‘bring to the front the common interests of the entire proletariat, independently of all nationality’ – had to be painstakingly worked out over a period of 60 years. A study of the disputes and an understanding of the significance of the trends which emerged in the international movement on these issues is therefore a precondition for re-establishing the communist tradition today.

The history of the international movement proper begins with the creation of the First International (1864) and it is to this that we will now turn.

THE FIRST INTERNATIONAL

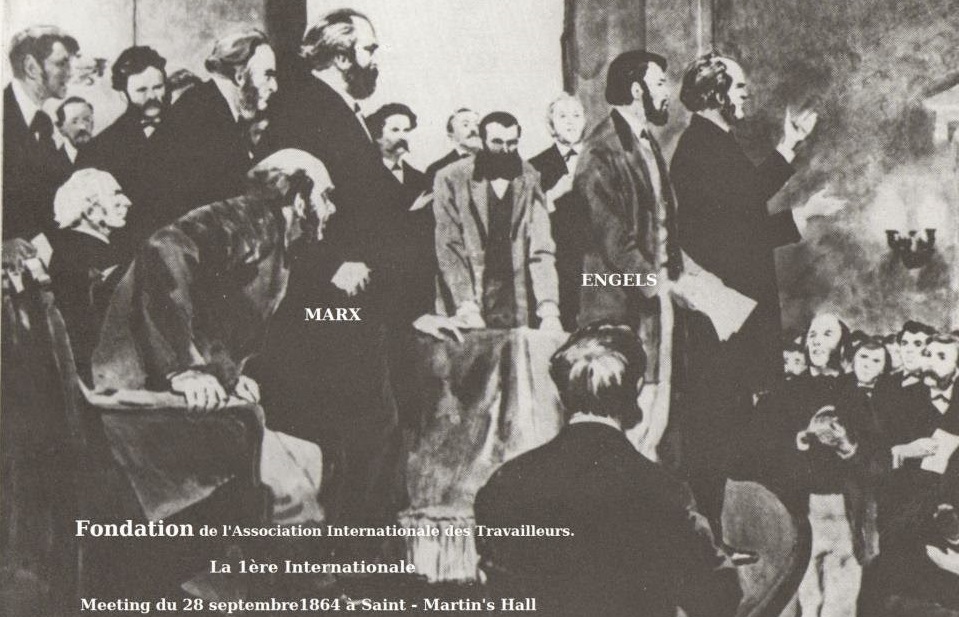

The First International was founded at a meeting in St Martin’s Hall, London on 28 September 1864. The initiative for its foundation came jointly from representatives of the British and French working class.

After the defeats of the 1848 revolutions in Europe and the Chartist movement in Britain, the 1860s saw a revival of working class movements both in Britain and France.

In Britain the crisis of 1858-9 and the lockouts and strike movements of the London building workers gave enormous impetus to the struggle for a nine-hour working day. In the wake of this nine-hours movement the London Trades Council (1860) was to be formed, and in October 1861 the Beehive – the most influential paper of its time in the labour movement in Britain – was founded.

The London Trades Council participated officially at the foundation meeting of the International and its secretary George Odger became the first and only President of the First International. The Beehive was later to become the first official organ of the International. And of the 27 Englishmen who were elected to the first Central (later General) Council of the International, at least eleven were from the building trade.

In the early 1860s the French workers were emerging out of a long period of severe repression arising from the defeats of 1848 and of Louis Napoleon III’s ‘Coup d’Etat’ in 1851. Napoleon III began making overtures to the working class, seeking a counterweight to the liberal bourgeois opposition to his regime. Trade unions were illegal in France although organisations of workers were allowed to exist under the guise of friendly societies. The working class unrest and strikes after the crisis of 1857-8 made new concessions necessary. In 1862 Napoleon III sponsored the sending of an elected delegation of French workers to the London International Exhibition. In these elections French workers were able to act independently for the first time since the Coup d’Etat. In Paris almost 200,000 workers elected 200 delegates – in the Provinces 550 delegates were chosen. While the deegation was genuinely representative of the French working class, there was no great enthusiasm from the English trade unions for a delegation from France which had the patronage of Napoleon III. Nevertheless a group of workers led by Toulain, a follower of Proudhon, did make contact with English trade union leaders. These contacts eventually led to further meetings which laid the foundation of the International. In 1863 Napoleon was forced by the dangers of revolution to tolerate a constitutional opposition in France – Toulain, in fact, stood as a working class candidate in the Paris elections of March 1863, although with little success. And in 1864 the Proudhonists issued the ‘Manifesto of Sixty’ which spoke bluntly of the conflict between labour and capital. The French working class were on the move again. Toulain and Murat, who signed the Manifesto, were at the founding meeting of the First International.

Three international events helped prepare the way for the formation of the International – all of them had an impact on the British working class.

The Italian Risorgimento – the mid-19th century movement for the unification and liberation of Italy – had sympathy among the radical lower middle class and the working class. When Garibaldi came to London in April 1864 London came out in force and witnessed the ‘largest procession of workers that London had ever seen’. When his visit was abruptly terminated by the government, demonstrations and protests by workers took place which led to clashes with the police.

More important still was the working class support for the North in the American Civil War in spite of the hardship imposed on textile workers in England by the Northern blockade of the South. A campaign of pro-Northern mass meetings played a major role in deterring the British government from intervening on the Southern side.

Finally the support for the Polish insurrection of 1863 was an immediate cause of the links between English and French workers which led to the founding of the International. At the end of January 1863 the Polish people had taken to arms and risen for the third time since 1830 against Russian domination. A provisional government had been installed which was only crushed by a strong military force sent by the Tsar after over a year of bitter struggle. A mass meeting was called by trade union leaders in England to demonstrate their solidarity with the Polish revolution. The Chairman of that meeting, Professor Beesly, was to act as Chairman at the foundation meeting of the International. At his meeting a delegation was elected to demand armed intervention by Britain against Russia in support of Poland. Contact was also made with French workers so that joint pressure could be put on both the English and French governments. In July 1863 Tolain and four other delegates from Paris travelled to London to speak at a meeting in support of Poland organised by the London Trades Council. Odger, later President of the International, and Cremer, its future Secretary, spoke at a reception for the French delegation the next day of the need for closer unity among the workers of all nations. An English committee was formed to draft an address to French workers which would include the idea of an international association of the working class. George Odger drafted the Address ‘To the Workmen of France from the Workmen of England’.

This Address followed the lines of earlier appeals for international working class solidarity which had gone out from the Chartists Harney and Jones, the Fraternal Democrats and their successors. It called for an international organisation of workers to oppose the international conferences and alliances of the rulers of the major nations. It called for international cooperation against the importation of low paid foreign workers by the capitalists in order to force wages down, with the object of organising for the raising of all wages. And it called for immediate action to defend Poland.

Three months passed before the British Address was sent off, and a further eight months before the French reply was received in London. By then the Polish revolution had been defeated. The meeting which was called to hear the exchange of addresses took place on 28 September 1864 in St Martin’s Hall, London. This was the founding of the First International. To be continued.