The imperialist wars waged by Britain and the US in Iraq and Afghanistan are destroying the lives of millions. With international capitalism becoming increasingly unstable, the brutal crisis of war and exploitation faced by masses in the ‘third world’ is set to continue. In Britain millions of working class people remain in poverty, health care and education are being cut back and racist and oppressive laws are piling up. But there is an alternative. In 1917 the oppressed people of Russia brought down the capitalist autocrats who had led their country to war and poverty, declaring socialism and communism as the only route to equality. Led by the Bolshevik Party, the Revolution sent shockwaves through the imperialist powers and inspired millions to fight for a better world. 90 years on and the Russian Revolution is gone, but its ideas are once again being picked up in Latin America. In Venezuela, Bolivia and elsewhere poor people inspired by the gains of socialism in Cuba are fighting for change. The Bolshevik Revolution is as relevant as ever.

Under the Tsar the people of Russia had been dragged against their will into the barbarity of the First World War, forced to fight for Russian imperialism. Thousands starved in the trenches and at home things were hardly better. From 1914 to 1917 the price of bread rose by more than 300% and pork by 770%; essentials like firewood and clothing soared to more than 1,000% of their original price.

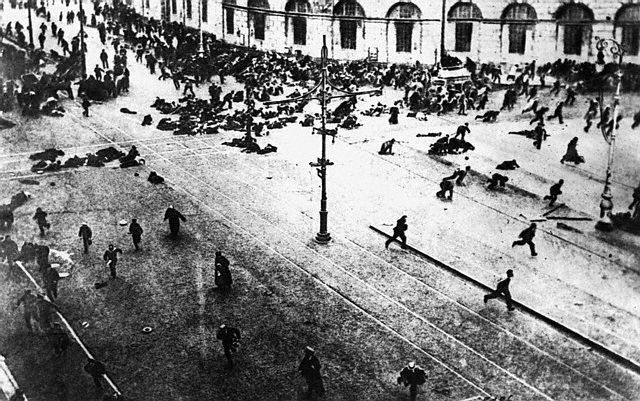

In February 1917, 31 months into the war, masses of impoverished workers and sections of the army demonstrated, demanding bread and an end to autocracy and war. Huge strikes and protests were met with violence as the state deployed soldiers and police to confront the crowds. On 26 February state forces massacred hundreds of protestors. The workers fought back and the Duma (parliament) was forced to persuade the Tsar to step down. Following their failure to convince Grand Duke Mikhail to take over, Duma officials formed a Provisional Government under Prince Lvov.

The Provisional Government was dominated by the nationalist Cadets (Constitutional Democrats) supported by the Mensheviks, the opportunist party of the reformist middle class which had split from the Bolsheviks in 1902, and the right wing of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, representing the better-off peasants. These forces, claiming to represent the majority of the Russian people, were to play a vicious role in attacking the revolutionary movement.

After February average wages increased by around 500%, but at the same time the price of necessities shot up further and the purchasing power of the rouble slipped by two thirds. By August food prices had risen 51% more than wages, despite strong harvests. Meanwhile the Duma refused to end Russian involvement in the war. It was clear that the bourgeois Provisional Government would be making no radical changes.

The Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies was set up by the radicalised masses in Petrograd city. Other Soviets (communal councils) sprang up across the country, creating a situation of dual power. In April Bolshevik leader Lenin wrote about Russia in a state of transition, urging opposition to the ‘would-be socialists’ in the government. Real socialism was the only solution:

‘the Russian Revolution of March 1917 not only swept away the whole Tsarist monarch, not only transferred the entire power to the bourgeoisie, but also moved closer towards a revolutionary-democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry. The Petrograd and other, local, Soviets constitute precisely such a dictatorship (that is, a power resting not on the law but directly on the force of the armed masses of the population)…’

In July thousands of soldiers rose up against orders to go to war. Demanding ‘All power to the Soviets!’ they were joined by hundreds of thousands of Petrograd citizens and were supported by the Bolsheviks. The government responded with brutality and on 4 July 400 were killed. Workers distributing the Bolshevik paper Pravda were shot in the streets and the newspaper’s offices destroyed. Hundreds were arrested. Alexander Kerensky, a Socialist Revolutionary, was made head of government and General Kornilov was put in charge of the army, declaring that every Bolshevik and Soviet member should be hanged. In September Kornilov led an attempted coup in Petrograd and was repelled by the masses, with many of Kornilov’s men won over to the side of the Soviets.

The Bolsheviks responded to government calls to disband the Soviets by calling for a Congress in November to take over the government of Russia. ‘The entire machinery set up by the Russian Revolution of March functioned to block the Congress of Soviets’ (Reed, p51*). An uprising was on the cards. Things were moving forward, fast.

By October the ruling class was in turmoil, and the masses were becoming more organised. On 10 October the Bolshevik Central Committee voted to organise an armed uprising. Two leading party members, Kamenev and Zinoviev were against, and, along with Riazanov, campaigned against it after the vote. They argued that the Bolsheviks didn’t have enough mass support, that the insurrection would be unsuccessful and that they should wait for a Constituent Assembly. Lenin responded vigorously: ‘Refusing to rise means to trust our hopes in the good bourgeoisie who have “promised” to call the Constituent Assembly…Either we must abandon our slogan, “All Power to the Soviets”, or else we must make an insurrection. There is no middle course.’

On 12 October the Petrograd Soviet established a Military Revolutionary Committee to plan the rising. The soldiers declared: ‘The Petrograd garrison no longer recognises the Provisional Government. The Petrograd Soviet is our Government. We will obey only the orders of the Petrograd Soviet, through the Military Revolutionary Committee.’ The Committee declared itself ready to resist counter-revolutionary attacks. Leader of the Petrograd Soviet Leon Trotsky said: ‘We hope that the All-Russian Congress of Soviets will take… into its hands that power and authority which rests upon the organised freedom of the people. If, however, the Government wants to utilise the short period it is expected to live…to attack us, then we shall have to answer with counter-attacks, blow for blow, steel for iron!’

On 25 October, the opening day of the Soviet Congress, the government was overthrown in Petrograd by the armed working class, with the support of sections of the army and navy; there was little bloodshed. Kerensky fled to organise the bourgeois resistance. Josef Stalin wrote an editorial in the Bolshevik newspaper on the morning of the rising: ‘After the victory of the February Revolution, power remained in the hands of the landlords and capitalists, bankers and speculators, profiteers and marauders – therein lay the fatal error of the workers and peasants… that error ought to be corrected at once.’ The Revolution spread like wildfire across the country. Women played an important role, as leading Bolshevik Alexandra Kollontai wrote later:

‘Who were they? Isolated individuals? No, there were hosts of them; tens, hundreds of thousands of nameless heroines who, marching side by side with the workers and peasants behind the Red Flag and the slogan of the Soviets passed over the ruins of Tsarist theocracy into a new future…’

US socialist John Reed witnessed events in Moscow, where ‘the Soviets had voted overwhelmingly to support the action of the Bolsheviks in Petrograd. Already a Military Revolutionary Committee was functioning. Everywhere the same thing happened… Old Russia was no more; human society flowed molten in primal heat, and from the tossing sea of flame was emerging the class struggle, stark and pitiless…’

Maria Spiridonova, leader of the Left Socialist Revolutionary Party, then supportive of the Bolsheviks’ actions, spoke at the 29 October Peasants Congress:

‘Before the workers of Russia new horizons open which history has never known… All workers’ movements in the past have been defeated. But the present movement is international, and that is why it is invincible. There is no force in the world that can put out the fire of the Revolution! The old world crumbles down, the new world begins.’

A Russian Soviet Socialist Republic was declared, with decrees on redistribution of land, the right to recall politicians from office, limits on wages of officials, nationalisation of the banks, and equal rights for all nationalities.

Immediately the Revolution was met with political hostility and military intervention from the imperialist powers. Soviet offers of peace, including the right of nations to self determination, were rejected and the Red Army fought back against the invaders. The imperialists, particularly Britain, France, Japan and the US, supported the counter-revolutionary White Russian forces which instigated the Civil War in 1918, and 12 foreign powers invaded Soviet territory; Japanese troops didn’t leave till 1922. Lenin affirmed: ‘This first victory is not yet the final victory, and it was achieved by our October Revolution at the price of incredible difficulties and hardships, at the price of unprecedented suffering… But the fact remains that for the first time in hundreds of years the promise “to reply” to war between the slave-owners by a Revolution of the slaves directed against all the slave-owners has been completely fulfilled – and is being fulfilled despite all difficulties.’

The Russian workers hoped their victory would be followed by revolutions in the advanced capitalist states of Europe, paving the way for communism internationally. In Germany the 1918 Revolution was defeated and leaders like Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were murdered at the hands of the traitorous Social Democratic Party, ‘socialists’ supportive of the war. The Soviet Union, established following the Bolshevik Revolution, was forced to begin building socialism alone. Lenin wrote: ‘We have made the start. When, at what date and time, and the proletarians of which nation will complete this process is not important. The important thing is that the ice has been broken; the road is open, the way has been shown.’

90 years on from the October Revolution the world is still shaking. In the decades that followed the example of the Soviet peoples’ struggle for social justice inspired revolutionary movements on all continents, with socialism on the agenda from China to Czechoslovakia. Years on, and never has the contrast between the human progress represented by socialism and the dog-eat-dog barbarity of capitalism been exposed to the world as starkly as it was with the collapse of the Soviet Union and socialist bloc. Russia witnessed the sharpest fall in life expectancy on record anywhere in the world and is today the playground of corrupt capitalists, growing fat while many starve. The black north American singer Paul Robeson was once able to write fondly about the lack of racism during his visits to the Soviet Union: ‘I feel like a human being for the first time since I grew up. Here I am not a Negro but a human being. Before I came I could hardly believe that such a thing could be. Here, for the first time in my life, I walk in full human dignity.’ But now organised fascism and racism are on the rise in Eastern Europe, as right wing reactionaries exploit the run-down state of society and economy.

But there is hope for the oppressed people of the world. Cuba holds the torch of socialism and the legacy of the Bolshevik Revolution. In turn it inspires millions to struggle against imperialism and capitalism for social justice

Louis Brehony

* Ten Days that Shook the World, John Reed, Penguin Classics.

FRFI 199 October / November 2007