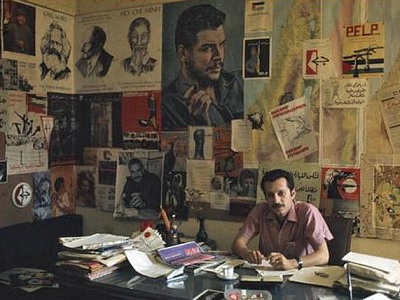

2017 marks 45 years since the murder of Palestinian writer, activist and political leader Ghassan Kanafani by the Israeli Mossad agency. On 8 July 1972, while living in Beirut, a car bomb explosion killed him along with his 17-year-old niece Lamees. Kanafani was one of the most important figures in 20th century literature. He was also a refugee, a revolutionary Marxist and an internationalist. The Israelis claimed the assassination was a response to the Lod Airport attack two months earlier, although Kanafani had played no direct role in this. He was, according to the obituary in the Lebanese Daily Star, ‘a commando who never fired a gun, whose weapon was a ball-point pen, and his arena the newspaper pages.’ Kanafani was at the time of his death the official spokesman of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and the editor of its paper Al Hadaf. The organisation saluted ‘the leader, the writer, the strategist, and the visionary.’

Ghassan Kanafani spent the early years of his life in the port city of Acre, where he was born in 1936. At the time of his birth, Kanafani’s father and other family members were participants in the national revolt against the British occupation of Palestine and its facilitation of Zionist colonisation. Acre was the site of a British occupation jail and of the executions of leading Palestinian activists. The epic song ‘From Acre Prison’ (Min Sijjn Akka) protests against their killing and remains an anthem of the Palestinian struggle. Prior to 1948, Acre had around 15,000 Palestinian inhabitants and no Zionist settlements. The Zionist attacks in the Nakba led to the expulsion of all but 3,000 Palestinians. 12-year-old Ghassan and his family became refugees in the town of Zabadiya, central west Syria, joining the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians exiled from their homelands.

After studying at university in Damascus, Kanafani became a teacher and journalist, working in Syria, then in Kuwait before ending up in Beirut. It was while working in refugee camps that Kanafani began writing his novels; his later interest in Marxist philosophy and politics came while living in Beirut. He was clear that:

‘My political position springs from my being a novelist. In so far as I am concerned, politics and the novel are an indivisible case and I can categorically state that I became politically committed because I am a novelist, not the opposite.’

Short stories, novels and poems

The themes of Kanafani’s writing were inseparably connected to the struggle of the Palestinian people over the course of his life. The Nakba is depicted vividly in works like The Land of the Sad Oranges (1963):

‘At Al-Nakura, our truck parked, along with numerous other ones. The men began to hand in their weapons to their officers, stationed there for that specific purpose. When our turn came, I could see the rifles and guns lying on the table and the long queue of lorries, leaving the land of oranges far behind and spreading out over the winding roads of Lebanon.’

‘After that day, life passed slowly…We were deceived by announcements…we were stunned by the bitter truth…Grimness started to invade the faces, your father found it difficult to talk about Palestine or the happy days in his orange groves…’

The refugees are central to his narrative. In the harrowing tale Men in the Sun (1962), a group of Palestinians are smuggled in the burning heat across Iraq and into Kuwait. They make it across the border but suffocate to death in the back of an oil tanker. The story is symbolic of the state of paralysis experienced by the refugees, where access to documentation could determine basic survival.

But Kanafani’s works were not tales of despair and hopelessness. Looked at collectively they speak of the problems and solutions of those expelled from their homes. In Return to Haifa (1970), he emphasises that ‘The greatest crime anybody can commit is to think that the weakness and the mistakes of others give him the right to exist at their expense.’ In other works he draws on the rising armed struggle for Palestinian liberation. The central figure of the short novel Umm Saad encourages her son to fight along with the guerrillas. According to Anni Kanafani, Ghassan’s wife, ‘Umm Saad was a symbol of the Palestinian women in the camp and of the worker class… it is the illiterate woman who speaks and the intellectual who listens and puts the questions.’

Activist-intellectual

In the years during which these literary classics were written, Ghassan had become an active member of the Arab Nationalist Movement, inspired by Gamal Abdul Nasser’s ideas of national independence and defiance of imperialism. But by 1961, the attempt at unification between Egypt and Syria (under a unified United Arab Republic) had failed, and the still firmly capitalist economy faltered. In the 1967 war, Israel dealt a heavy defeat on Egypian-led resistance. The decline of Nasserism took place alongside the rise of explicitly communist leadership in the anti-imperialist struggles then taking place throughout the world – Cuba, Mozambique and, with growing international significance, Vietnam. During these years Kanafani, along with his comrade George Habash, began to make a more serious study of Marxism, arriving at the conclusion that the political crisis in the Arab world and the ascendancy of imperialism and Zionism could only be solved by turning the anti-imperialist struggle into a social revolution.

As a PFLP leader, Kanafani turned his pen to overtly political questions, reflecting the urgency of developing the Palestinian national liberation struggle by the end of the 1960s. He increasingly dedicated his time to publishing work on the historic struggles of the Palestinian people, resigning from a well-paid job at the Nasserist magazine al Anwar to edit the PFLP newspaper Al Hadaf (The Target). The 1969 document Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine was co-authored by Kanafani and applied a Marxist analysis of class to the forces involved in the revolutionary movement, discussing its prospects and political strategy. The Resistance and its Problems, a pamphlet written by Kanafani and published by the PFLP in 1970, is a critical discussion on leadership, Marxist theory and practice, in the national liberation struggle.

In the pages of Al Hadaf, Kanafani called for ‘all facts to the masses.’ Perhaps his most important overtly political work was his detailed analysis of the 1936-39 Palestinian revolt. Kanafani wrote of the 1935 martyrdom of Sheikh Iz Al Din Al Qassam in an influential article first published in an early PLO magazine Palestinian Affairs (Shu’un Falastiniyeh) and later distributed as a pamphlet on armed struggle by the PFLP. In The 1936-39 Revolt in Palestine, finished in the year of his death, Kanafani details the structure of Palestinian society, the rise of Zionism, the failures of the left and, perhaps most crucially in the run-up to 1948, the weakening of the revolutionary movement by the ruthless British imperialist regime. Its violence was ‘unprecedented’, and ‘it was during the years of the revolt – 1936-1939 – that British colonialism threw all its weight into performing the task of supporting the Zionist presence and setting it on its feet.’ In this work he spares none of the reactionary Arab regimes from his ruthless criticism.

Anti-imperialism

Kanafani played a major role in raising consciousness of this period in anti-imperialist struggle and was an uncompromising internationalist:

‘Imperialism has laid its body over the world, the head in Eastern Asia, the heart in the Middle East, its arteries reaching Africa and Latin America. Wherever you strike it, you damage it, and you serve the world revolution.’

Kanafani’s descriptions of imperialism are characteristically graphic. He pointed to the international significance of the Palestinian struggle.

‘The Palestinian cause is not a cause for Palestinians only, but a cause for every revolutionary… as a cause of the exploited and oppressed masses in our era’.

In the memoir which Anni Kanafani published after her husband’s death, she wrote:

‘His inspiration for writing and working unceasingly was the Palestinian-Arab struggle…He was one of those who fought sincerely for the development of the resistance movement from being a nationalist Palestinian liberation movement into being a pan-Arab revolutionary socialist movement of which the liberation of Palestine would be a vital component. He always stressed that the Palestine problem could not be solved in isolation from the Arab World’s whole social and political situation.’

We should not forget, of course, that 17-year-old Lamees was murdered alongside him in the car bombing. Ghassan’s sister Fayzeh reflected:

‘Just the previous day Lamees had asked her uncle to reduce his revolutionary activities and to concentrate more upon writing his stories. She had said to him, “Your stories are beautiful,” and he had answered, “Go back to writing stories? I write well because I believe in a cause, in principles. The day I leave these principles, my stories will become empty. If I were to leave behind my principles, you yourself would not respect me.” He was able to convince the girl that the struggle and the defence of principles is what finally leads to success in everything.’

Kanafani’s class analysis was ahead of its time in the Palestinian movement and pointed to the dangers ahead if the bourgeois trend in the PLO leadership went unchecked. Negotiations with the Israeli leadership, he said, would be ‘a conversation between the sword and the neck… I have never seen talks between a colonialist case and a national liberation movement.’

Ghassan Kanafani was murdered for his commitment to Palestinian resistance. Like Basil Al Araj, gunned down in February this year, he was seen by the Israeli occupiers as a threat to the racist occupation regime. His legacy lives on in every Palestinian and internationalist willing to fight for the anti-imperialist cause. Speaking to students he once said,

‘The goal of education is to correct the march of history. For this reason we need to study history and to apprehend its dialectics in order to build a new historical era, in which the oppressed will live, after their liberation by revolutionary violence, from the contradiction that captivated them’.

Louis Brehony