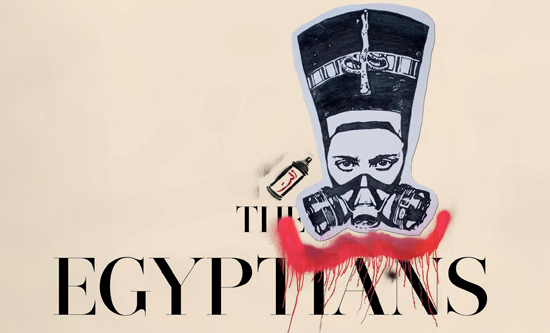

The Egyptians: a radical story

Jack Shenker, Allen Lane/Penguin

2016, 544pp, £15.99

This wonderful book is written by Jack Shenker who was Egypt correspondent for The Guardian newspaper in 2011 and reported regularly on the Arab Spring. Five years on, most readers will remember the 18-day occupation by hundreds of thousands of people of Cairo’s Tahrir Square. According to dominant media accounts at the time, it was this defiant occupation of public space that started off a turbulent chain of events which led to the overthrow of the government of President Mubarak, the election of President Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood, his subsequent overthrow by popular pressure and the installation of Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, chief of the Egyptian Armed Forces, as the new President of Egypt in 2013.

Shenker describes all of this and provides an excellent guide to the protagonists. Moreover his account makes a distinguished contribution to our understanding of these events. He situates this history in the crisis of the capitalist system, globalisation and the imposition of structural adjustment programmes on centralised states to open them up to multinational corporations and privatisation. Through this study of the material conditions that gave rise to the revolution – and with it, the counter-revolution – Shenker challenges the dominant media version. He says that Egypt’s revolution has been deliberately misinterpreted in the service of elites within and outside Egypt. In Shenker’s view, the Arab Spring has been deceptively framed as an anti-government protest against the dictatorial Mubarak regime, which then led to a power struggle between Islamists and secularists, and concluded with the establishment of a strong but uncorrupted leader from the army who ended social chaos and brought peace to warring factions that were tearing the country apart.

This ruling class view, says Shenker, deliberately leads to the conclusion that mass mobilisations are doomed to fail. It wipes from the record the presence of Egypt’s living revolutionary forces that are the subject of this book. Deliberate misinterpretation of the Arab Spring serves the interests of the imperialist powers who are conducting wars and occupations in North Africa and the Middle East. The outcomes of brutal military interventions and the shifting political alliances of the ruling class leave no space for citizens. Diplomacy hides the real agenda of power and opportunism guides the actions. Among those who visited Tahrir Square early in 2011 to show support for ‘democracy’ were Prime Ministers David Cameron and Kevin Rudd of Australia, Catherine Ashton, then EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security, Hillary Clinton, US Secretary of State, and John Kerry, chair of the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. Clinton had no worries about switching loyalties, having stated in 2009: ‘I really consider President and Mrs Mubarak to be friends of my family’. At the same time President Barack Obama described Mubarak as ‘a leader and a counsellor and a friend to the United States’, as indeed he had been. Egypt had been conscripted into the ‘War on Terror’ and the country handed over as a base for the CIA’s extraordinary rendition programme, in return for which the Mubarak regime had received more annual military aid than any other nation except Israel.

The grievances of the millions of protesters who took to the streets in Cairo, Alexandria, the port city of Suez and dozens of towns and villages in 2011 remain today. The people rose up against police brutality, state-of-emergency laws, control of the electoral system, corruption, high unemployment, food price inflation and low wages. Striking trades unionists came out in solidarity with the call for rights in the ownership and control of Egypt’s resources.

To frame Tahrir Square 2011 as a single historical event is to conceal the radicalism of an Egyptian people still in struggle, a living revolutionary movement involving all sectors of society: the farmers, factory workers, urbanised slum dwellers, the marginalised poor and students. It is a movement that challenges sectarianism, militarism and gender and cultural oppression. It is a movement, above all, that is still being generated by the rapacious forces of neoliberalism appropriating its natural resources.

Shenker discovers this living movement through meetings, interviews and friendships, visiting farming and fishing communities, those involved in housing struggles, underground counter-cultural rap and graffiti communes, churches and mosques. Egypt is a young country, with 75% of the 96 million population under the age of 25 and only 3% over 65 years. In this dysfunctional economy, unemployment among university graduates is ten times that for those leaving elementary school. Investment and economic expansion is calculated on the basis of a cheap and unorganised labour force. Entry to the skilled professional sector has been closed off by a failing and under-resourced state infrastructure. The provision of schools, hospitals, roads and public transport has been, as the author says, ‘sealed off and commodified for the purpose of private gain’.

In three sections Shenker investigates the rise and fall of the centralised state provision of health, education, infrastructure and modest land redistribution that was the legacy of the Nasser regime. In Part One, ‘Mubarak Country’, the regime made deals with the IMF, World Bank and USAID, imposing structural adjustment programmes and enriching themselves on the way. Over a million families, more than one third of Egypt’s farmers, were left without land after the introduction of Law 96 in 1992 which returned land to pre-1952 large landowners or their descendants. Part Two, ‘Resistance Country’, reports on the varied and creative acts of resistance, occupations, community councils and strikes which grew into many Tahrir Squares in 2011. In Part Three, ‘Revolution Country’, Shenker tours Egypt, recording the devastation caused by multinational companies enforcing an agricultural production model based on exports rather than domestic demand, enabling food companies like Heinz, Unilever, Cadbury, Danone and Coca Cola, as well as Gulf-based conglomerates Dina Farms, Juhayna and Wataniya Poultry, to extract huge profits, impoverishing the workforce and the environment.

But no longer are the people silent in the margins. Acts of solidarity in Tahrir Square are not forgotten, as when Muslim youth formed a protective barrier against attacks on Coptic Christians by sectarian forces. The children of Zawyet el-Dashour school, 20 miles south of Cairo, play games of revolution, having ensured the removal of their headteacher for corruption, disrespect and breaking his promise to hold a football tournament.

The Presidency of Sisi was welcomed by those same imperialist leaders who showed up to praise ‘democracy’ in Tahrir Square five years ago. Egypt is once again a safe ally of the West. Sisi held a Downing Street meeting with Prime Minister Cameron in 2015, while thousands of political activists remain in prison and torture is rife. Yet still the people of Revolution Country are not silenced. This is the message of Shenker’s book, a kind of travellers’ guide to the necessary world of the people’s resistance and their demand for justice.

Susan Davidson

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! 251 June/July 2016