The escalating housing crisis reflects the determination of the British ruling class to make the working class pay for the wider crisis of the capitalist system. The policy of tackling inflation by raising interest rates – with seismic repercussions in the housing sector – is deliberately aimed at reducing ‘disposable income’, ie slashing the living standards of the working class. If soaring rents and mortgages mean sections of the working class can no longer afford to buy essentials like food and clothing, well, that’s simply not capitalism’s problem. As the Bank of England wrote in June, announcing its 13th consecutive hike to the base interest rate since December 2021:

‘The distribution of where and by whom the impact of policy tightening is borne is not the responsibility of the central bank, however… if we accept that rising rents are linked to changes in Bank Rate then in aggregate the impact of rising rents will be just the same as changes in mortgage interest rates in that it will reduce the amount of disposable income households have and in the process reduce aggregate demand and hence inflation’ (quoted by Louis Ashworth in Financial Times, 7 July 2023).

The rich, of course, remain immune – the estate agents Savills reports that at the prime end of the property market, affluent buyers are increasingly choosing to buy outright. For poorer workers, concentrated in the private rented sector, the situation is becoming intolerable. But even better-off workers, who bought into the dream of homeownership when interest rates were at record lows, or were seduced by the glittering promise of ‘affordable’ options like Help to Buy and Shared Ownership, are now being sacrificed on the altar of profitability.

The dream turns sour

The Bank of England raised its base interest rate by half a percentage point to 5% on 22 June, driving up an average two-year fixed rate mortgage to 6.7% – higher than at any time since August 2008. Approximately four million homeowners coming off fixed-rate deals over the next three years will find themselves paying on average £280 a month more; those in their 30s face an additional £360, while nearly a million households will see repayments rise £500 or more. First-time buyers – generally younger people – are now spending up to 40% of their income on mortgage repayments; in London that figure rises to 66%. Three in ten mortgage holders report finding it increasingly difficult to afford adequate food or pay energy bills. Arrears on mortgage repayments had already risen by nearly 10% in the first three months of the year. The consumer financial adviser Martin Lewis has described this as ‘a ticking mortgage bomb… that’s now exploding’.

The government, mindful of the potential political repercussions of a wave of repossessions ahead of a general election next year, has put pressure on mortgage lenders to play nice, for example by offering longer-term loans. However, bound as it is by Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s promise to reduce inflation, it has refused any additional support. After all, if it isn’t hurting the working class, it isn’t working to stabilise the capitalist economy. While repossessions remain low (compared to the period following the 2008 financial crash) they are nonetheless increasing steadily. Government figures show that, compared to the same quarter in 2022, in May 2023 mortgage possession claims increased from 2,889 to 4,035 (40%). At the end of last year – when mortgage rates were still under 6% – the Joseph Rowntree Foundation calculated an extra 120,000 households would face poverty when their current mortgage deal ended, swelling the ranks of the 2.4 million people with a mortgage already living in poverty (see ‘Property snakes and ladders as mortgage rates rise’, FRFI 292, December 2022/January 2023).

Those most affected are young homeowners, about 24% of the total. Many of these will be formerly better-off workers whose standard of living is being steadily eroded. But the government clearly calculates that it is more important to appease its core electorate – the two-thirds of homeowners aged over 65 who own their homes outright and have seen the value of their properties rise exponentially.

What is meant today by housing shortage is the peculiar intensification of the bad housing conditions of the workers as the result of the sudden rush of population to the big towns; a colossal increase in rents, a still further aggravation of overcrowding in the individual houses, and, for some, the impossibility of finding a place to live in at all. And this housing shortage gets talked of so much only because it does not limit itself to the working class but has affected the petty bourgeoisie also.

Desperate times for private renters

The mainstream media and politicians have focused almost exclusively on the problems faced by those owning mortgages. As Frederick Engels pointed out in The Housing Question 150 years ago, ‘this housing shortage gets talked of so much only because it does not limit itself to the working class but has affected the petty bourgeoisie also’. But the situation facing the 20% of households who rent privately is far more desperate. The Office for National Statistics found in June that those renting privately were five times more likely to be experiencing financial hardship than those paying mortgages. Private-sector rents rose an average 5.1% in the 12 months to June, faster than at any time since records began in 2016 – and at around 10% for new lets. Half of all small landlords have buy-to-let mortgages and many are passing on costs to their tenants, or simply selling up, reducing the number of homes for rent. They are under no social obligation to house the working class, and will simply transfer their capital to something more profitable. Buy-to-let landlord sales have outstripped purchases for the last seven years. In part this is inevitable: a report in May from the cross-party select committee on levelling-up says MPs were told that ‘policy since 2015 had been designed specifically to [encourage smaller landlords to leave the sector] as the government wanted to see the sector consolidated in the hands of fewer but larger landlords or at least cool the buy-to-let market’. As a result, the number of homes available to rent is down 57% compared with 2019; in major cities rental agents report 20 people chasing each vacancy, with prospective tenants encouraged to outbid each other on how much they are prepared to pay to secure a roof over their heads.

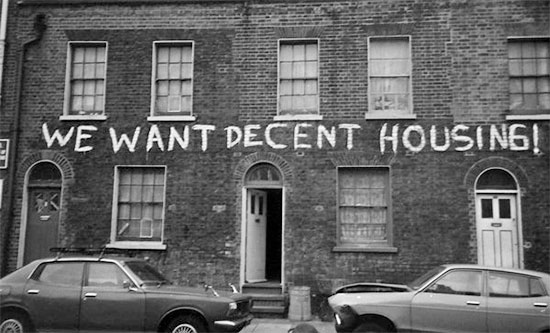

For the poorest, of course, this is simply not an option. With housing benefits frozen at their 2020 levels, in June the Institute for Fiscal Studies found that just 5% – one in 20 – dwellings in the private rented sector across the country were now affordable for those in receipt of Local Housing Allowance (LHA). In April 2020, the figure was 23%. Two million households in Britain are in receipt of LHA, forced to rent the very worst and most overcrowded properties. This is indeed a return to the slums, that will be exacerbated by the government’s promise to allow even more commercial properties in cities to be converted into flats. More than a quarter of homes in the private rented sector already fail to meet decent homes standards. Meanwhile, more than four years after it was first promised, the Renters’ Reform Bill continues to crawl through parliament, meaning tenants can still be evicted under the infamous ‘no fault’ Section 21 if they complain to a landlord about conditions or attempt to resist exorbitant rent rises. By May, Section 21 evictions had risen 91% on the previous year.

No solution under capitalism

By and large, the capitalist state has no interest in housing the working class. As late as the 1930s the poorest workers were reduced to sleeping slung over a rope, the so-called ‘Twopenny Hangover’. Today, those who cannot find or afford anywhere to live may end up in a tent in the park, or sleeping in their cars. The number of people in employment who are homeless is rising. Of the 72,790 households threatened with homelessness in England in 2022, one in four had at least one person in work – an increase of 22% compared to the same period two years earlier. Overall, by the end of March this year, almost 105,000 households in England, including 131,000 children, were in temporary accommodation – the highest number in 25 years. This is the result of years of failure by successive Conservative and Labour governments to provide affordable housing. The only time the capitalist state came anywhere near addressing the housing needs of the working class was in the exceptional conditions of the postwar period, when it exploited the resources of its former colonies to expand state welfare in Britain on a mass scale. Today those conditions no longer exist.

So when Levelling-Up Minister Michael Gove says the government will tackle the housing crisis by building 30,000 homes for social rent a year, it is an empty gesture. Since 2013, of 257,000 ‘affordable rent’ homes (up to 80% of market rent) built in England, just 66,635 were for social rent. In each of the last five financial years, two-thirds of councils failed to build a single home. Meanwhile, although 7,644 social rent homes were built between 2021 and 2022, 24,932 were sold off under Right to Buy and 2,757 were demolished. Sales of social housing homes have significantly outpaced those built throughout the past decade. Only one of every five new homes built over the last year was in the ‘social rented sector’ – with the majority falling into the ‘affordable’ tenure, which includes Shared Ownership. This is while a million households languish on council housing waiting lists, some of them for years. Even within its own misleading definitions, government initiatives are failing: in December 2022, a £21bn government programme for the building of ‘affordable’ homes – half of which had to be for private sale – missed its target of 180,000 homes by 32,000 units. This is the same Michael Gove who has just handed back to the Treasury £1.9bn meant to be used to tackle the housing crisis. That money constituted about a third of his department’s entire housing budget, including £255m for new affordable housing and £245m for building safety: apparently they ‘couldn’t find anything to spend it on’.

Meanwhile, waiting in the wings, Keir Starmer says Labour will be the party of housebuilding and home ownership – ‘the builders, not the blockers’. While this is clearly an afterthought – housing does not even make it onto his ‘five pledges’ for a future Labour government – it is also completely pie in the sky.

The Home Builders Federation warned in February that housebuilding in England in 2023 would fall to its lowest level since the Second World War. Barratt Developments, Britain’s biggest housebuilder by volume, says it will build 20% fewer homes this year. The other big housebuilders are following suit. Like landlords, they are under no obligation to provide homes, however great the need, and will not do so unless they can guarantee adequate profits. With house prices faltering – 3.5% lower in June compared with a year earlier, the sharpest rate of decline since 2009 (although still well above pre-Covid levels) – they will restrict how many get put onto the market and attempt to boost their profit margins in other ways. For example, the attack on ‘planning regulations’ is largely fuelled by councils’ insistence on a modicum of social housing on any new developments, something the big developers like to argue makes their plans ‘unviable’. A more recent line of attack has been on environmental regulations, which they have been lobbying the government to ease. In any case, they are well placed to ride out the storm. In 2021 the nine biggest housebuilders in Britain registered profits of £2.8bn – ten times higher than in 2007. Barratt alone registered returns of over 30% at the end of last year. And while Savills concedes that rising interest rates will exert a downward pressure on land values, it is optimistic that continued high demand for housing will sustain prices over the medium and long-term.

The housing crisis is created and sustained by capitalism itself. Until it becomes a social problem for the ruling class – until the anger and despair it generates manifest themselves in resistance on a scale that cannot be ignored – this crisis will continue to blight the lives of millions of working class households. The time for that resistance is now.

Cat Wiener

FIGHT RACISM! FIGHT IMPERIALISM! 295 August/September 2023