The World Bank recently announced that extreme poverty is expected to rise for the first time in 20 years following the economic fallout in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, with ‘most countries experiencing drops in labour incomes of a magnitude rarely seen on the national scale.’ Prior to the pandemic, the global rate of extreme poverty was expected to decrease from 8.4% (643 million) in 2019 to 7.9% (615 million) in 2020, however it is now expected to increase to between 9.1-9.4% (703-729 million), a loss of 3 years’ worth of progress.

Historically, the global rate of extreme poverty decreased by around 1% on average between 1990 and 2017 but had slowed to 0.5% in recent years; a bad portent for the World Bank’s aim of reducing the global rate of extreme poverty to 3% by 2030. The priests of global capital at the World Bank have set similar (repeatedly missed) goals for decades, as part of their ideological goal to prove that global capitalism can eliminate extreme poverty but the recent stalling in reducing it has been exposed as a lie. Now they’re going to want a miracle; assuming a return to prior levels of economic growth by 2021, the World Bank predicts that the rate of extreme poverty will reach between 6.7-7.0% (573-597 million) in 2030, twice their intended goal!

Crisis for workers worldwide

The report from the World Bank (October 2020) highlights how ‘emerging evidence shows that people who are currently poor or vulnerable are being hit especially hard’, consisting of ‘less-educated’ and lower-paid workers in labour-intensive jobs. These are, broadly speaking, those who work in retail, restaurants, small businesses, construction, etc and similar insecure and similar low-paid work. These workers risk exposure to Covid-19 in their workplaces and if they are forced to quarantine or their workplace closes, they cannot work from home. Low-skilled workers in poorer countries may have less resources to call upon if they should become unwell or unemployed and rely more on physical payments due to the lack of e-banking infrastructure, increasing the difficulty to receive government support payments even if their governments can offer it to them.

Furthermore, ‘Labour incomes of (low-income) households and of low-skilled workers are disproportionately affected by the adverse health and economic costs of the Covid-19 pandemic. In some cases, the impact is direct and immediate: poor workers who are more likely to suffer from health conditions, are older and who cannot afford protective equipment are more likely to contract Covid-19, stop working and lose earnings.’

A startling example of the effect of Covid-19 is illustrated by Nigeria, where 85% of households experienced rising food prices and half had reduced their food consumption as a result. In Nigeria in 2018, the metrics of ‘multidimensional poverty’ showed that 39.4% of the population were deprived of electricity, 44.9% of sanitation and 27.5% drinking water, painting a stark picture of conditions prior to Covid-19 and frustrate the fight against it.

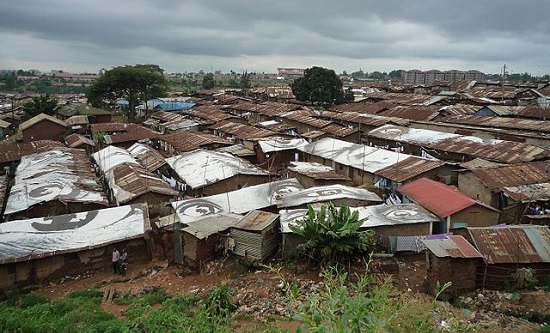

Those in extreme poverty are ‘largely rural, young and under-educated’, however a higher proportion of the ‘new poor’ are expected to live in urban areas, have better access to amenities like electricity, be better-educated than the ‘chronic’ poor and live in so-called ‘middle-income’ countries and in those experiencing ‘medium-intensity’ conflict. This is the section of workers whose pre-Covid-19 incomes and conditions already set them precariously above the boundary of extreme poverty and the majority of whom (57%) are employed in agriculture, hunting or fishing.

What is extreme poverty?

The World Bank sets the threshold of extreme poverty at US$1.90 per day per individual for their consumption, adjusted for the different cost of a ‘basket of goods’ from country to country. By this standard, one might consider the reduction of those in extreme poverty from around 1.9 billion (36%) in 1990 to 643 million (8.4%) in 2019 as a laudable achievement for global capitalism. However, the threshold of $1.90/day (it was raised from $1/day in 2015) is a dubious measure of poverty.

Economic anthropologist Jason Hickel argued in The Guardian in 2019, ‘Scholars have been calling for a more reasonable poverty line for many years. Most agree that people need a minimum of about $7.40 per day to achieve basic nutrition and normal human life expectancy… many scholars, including Harvard economist Lane Pritchett, insist that the poverty line should be set even higher, at $10 to $15 per day.’ If a threshold of $7.40/day is set: in 1981, 3.2 billion (71%) lived in extreme poverty, ballooning to 4.2 billion (58%) in 2013 (‘A letter to Steven Pinker’, 29 January 2019). The World Bank is revealed for what it is: the white washer of vast impoverishment under global capitalism which is driving endless imperialist wars, ecological catastrophe and climate change. The global masses, as the creators of global wealth, should reject the offensive prescriptions of the World Bank and imperialism, unite and fight for socialism, the only economic system which can cast poverty into the dustbin of history once and for all.

James Powalski