On 20 December 2015 Spain’s general election resulted in an unprecedented situation where no party gained a clear majority. The conservatives of the Partido Popular (PP) got 28.72% of the votes while the social democrats of the Socialist Party (PSOE) received a 22.02% share. Some new parties entered the parliament, in particular the right-wing Ciudadanos, (13.93%) and the social-democrats of Podemos (12.67%). The various parties trade accusations on a daily basis and hold tense negotiations but the result remains uncertain. Meanwhile, Catalonian parties have reached a last-minute agreement to establish a regional government which will pursue independence. However its stability is still in doubt after several months of negotiations. Contradictions arise and a complex time lies ahead, making it difficult to predict whether austerity policies will continue or whether there is a chance for change. JUANJO RIVAS reports from Madrid.

Catalonia

After the elections in Catalonia last September, the separatist parties relentlessly chased what seemed to be an impossible agreement. On 9 January 2016, right before the deadline, Carles Puigdemont was appointed president of the regional parliament. The anti-capitalist Popular Unity Candidacy (CUP), which had won ten seats, held the key to establishing a government, and demanded of the bourgeois Junts pel Sí party that the previous president, Artur Mas, stand down. Junts pel Sí refused. CUP had two possible strategies: to press ahead with its social agenda and thereby risk the possibility of new elections, or reach an agreement on basic programmes to keep the project for independence alive. Over 3,000 members assembled to discuss and vote, but failed to reach a decision. Neither side wanted new elections, and continued to challenge each other until the last possible moment. Finally, Junts pel Sí agreed to replace Mas with Puigdemont. However, the CUP has paid a high price for the deal as some of its most radical elected candidates were forced to resign and some social issues were compromised. The independence project goes ahead, but some class politics may have been blunted by the negotiations.

Instability in Spanish politics

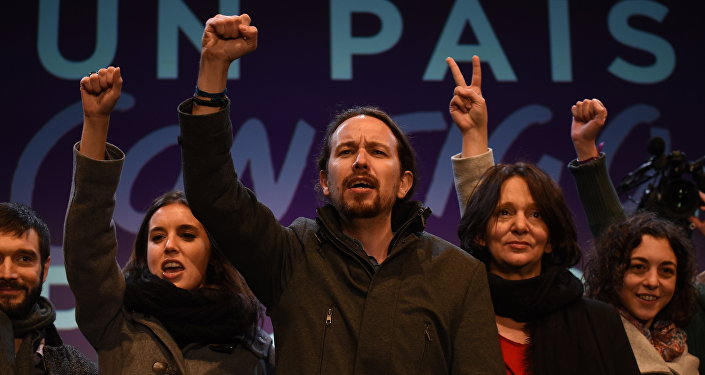

The December general election had a 73.20% turnout, 4.5% higher than in 2011. The two-party system has taken a severe hit: the PP lost 3.65 million votes and the PSOE 1.47 million. Including votes for its regional allies in Galicia, Valencia and Catalonia, the moderate left-wing Podemos raised its share to 20.66%. They aimed to form four parliamentary groups in a joint coalition; however, the electoral commission ruled this unlawful. The reactionary voting laws in Spain mean that the right-wing conservative PP got one MP for each 58,664 votes, whereas the anti-capitalist People’s Unity required 461,566 for each of its two parliamentary seats.

Political leaders play with hints, while the mainstream media speculates as to which moves are more or less likely to build a coalition government. The obvious alliances of PP and Ciudadanos on the one hand, or PSOE with Podemos on the other, are both insufficient to form a stable cabinet. According to protocol, King Felipe has been meeting party leaders to check their plans and possibly make a proposal for president, but neither Rajoy (PP) nor Sanchez (PSOE) are willing to submit their candidature without enough seats to ensure a parliamentary majority. As we go to press, a second round of talks is taking place; a decision has to be made before mid-March, otherwise another election will be called.

Corruption

Spain continues to be awash with cases of corruption. One MP for the PP is being investigated for receiving illegal commissions from Spanish companies in return for concessions in Algeria and South America. It has not stopped him from collecting his deputy credentials and embarrassing Rajoy by attending the first session of parliament. On 11 January, the trial against the king’s sister, Cristina de Borbón, and her husband on corruption charges started. In addition, 13 executives of a state-run water company have been arrested for granting fraudulent allocations and illegal concessions in exchange for trips and gifts. Five of them are in prison. The accused are close collaborators of Rajoy’s cabinet. Experts estimate the fraud amounts to at least €20 million. In previous issues we have reported on the network of corruption that surrounds the PP, where five of the six treasurers it has had since its foundation are under investigation. When the police seized the last treasurer’s computer they found its hard disk deleted; the party has been formally accused of concealing evidence.

Given the corruption scandals engulfing the PP, other groups feel uneasy about openly suggesting pacts with them. In any case, at least a three-party alliance is necessary to unfreeze the situation. Apart from new elections in spring, there are two possible scenarios. The first one is a ‘grand coalition’ of PP, PSOE and Ciudadanos: such a solution would mean complying with the demands of the troika of the European Union, European Central Bank and IMF, blocking any possibility of reforming the Constitution or questioning the unity of the country. Needless to say this is the market’s favourite option, and managers of large corporations rushed to suggest it before the cameras. Executive advisers like the son of former PP president Aznar warn international investors against instability and advise them to withdraw their funds from the country if the final result is different. The second option is a left coalition involving PSOE, Podemos, People’s Unity and left-wing nationalists, in imitation of the Portuguese strategy and to build an ‘anti-austerity bloc’ in southern Europe. The social-democrats of PSOE are the weakest pieces on this chessboard and they have yet to decide which way to turn. During the campaign they repeatedly rejected the possibility of a pact with ‘the party of the cuts and corruption’ (PP) as well as with ‘the populists who want to break Spain’ (Podemos). Podemos accepts the possibility of a referendum in Catalonia – a red line that the PSOE is not willing to cross – but its own strategy for electoral growth is based on undermining PSOE and winning the vote of its base, as Syriza did with PASOK in Greece. Turbulent times lie ahead before it becomes clear what path the political parties will tread.