‘Normalisation is normal as defined by Britain; it’s not defined by people like me or you.’

‘Normalisation is normal as defined by Britain; it’s not defined by people like me or you.’

On Sunday 29 May, around 1,500 people marched in Glasgow to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the Irish hunger strike in which ten republicans gave their lives in the struggle against British rule. The event was organised by the 1980-81 West of Scotland Hunger Strike Commemoration Committee. The march was made up of working class men and women from across Glasgow and Lanarkshire; there was a noticeable absence of any of the groups on the left aside from supporters of Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism!.

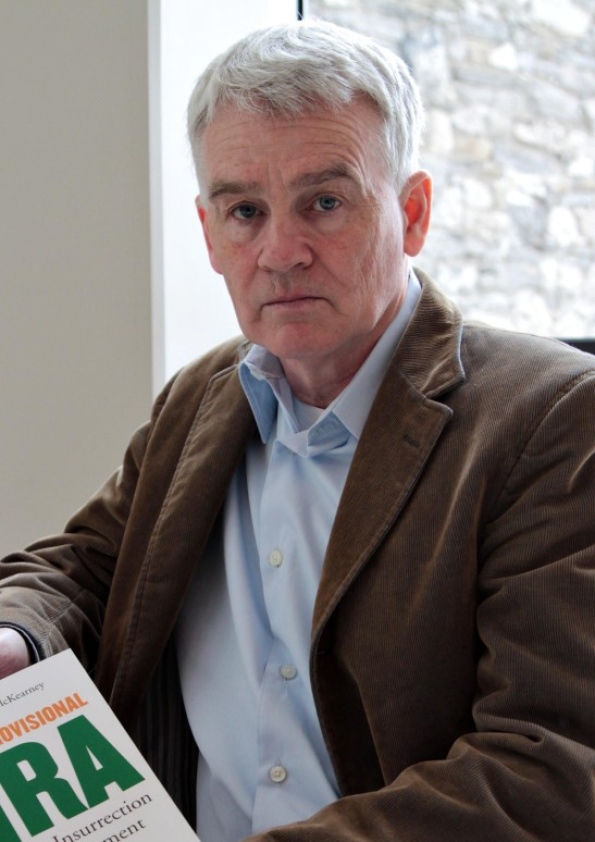

One of the speakers at the rally was Tommy McKearney, who joined the Republican Movement in 1971, becoming Officer Commander of the IRA’s Tyrone Brigade. He lived underground from the commencement of internment without trial in August 1972 until his eventual capture in October 1977; he was tortured by police officers in the notorious Castlereagh interrogation centre and sentenced by a non-jury Diplock court, to life imprisonment for the killing of a member of the British Army, Ulster Defence Regiment, based on ‘confession’ evidence. He joined the blanket protest and the first hunger strike, spending 53 days without food between October and December 1980, before the protest was called off. After the summer long hunger strike of 1981, he became Education Officer for IRA prisoners in Long Kesh. Following the Sinn Fein decision to drop abstentionism in 1986, he left along with other prisoners to form the League of Communist Republicans. He was released in 1993 and was to become one of the most articulate critics of Sinn Fein’s accommodation with British rule. After the march, Paul Mallon and Connor Riley spoke to him on behalf of Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism!

Can you start by outlining what you are doing now?

At the moment I am working for the most part politically with the Independent Workers’ Union. I still play a part within Republican politics – usually on a broader basis, than anything narrowly party political. The other piece of work I do day-to-day is for a community group based in Monaghan, addressing conflict resolution and while in some ways that sounds like a bit of a cop-out it has allowed me to engage with different members of the protestant working class and loyalist community, and its not all just for show sometimes we find it useful just to allow us to find out what the different conditions are in our communities.

We marched today to commemorate the hunger strike, 30 years on what lessons should we take from that period? Would you say that the hunger strike was a victory or a defeat?

I suppose at the risk of being ambivalent, it wasn’t either. There was limited success and the potential for defeat was there. On the one hand the hunger strike ended without the prisoners gaining any of their immediate demands; in the immediate aftermath of that the British government conceded three very important demands. Now I think it would be fair to argue that the British did that as a result of the hunger strike and they were using the old one about not being seen to give in to terrorists, so as soon as the strike ended they enacted quite significant reform.

But the hunger strike never really was solely about prison conditions; it was much wider than that. It demonstrated the depth of determination and commitment of resistance among the republican community. It also demonstrated to ourselves and the world at large that we had significant popular support in the nationalist and republican community in the Six Counties, with a potential for extending it wider.

But I would say that it failed insofar as lessons, advantages and from that period, which were partly a result of the commitment of the men prepared to give their lives, and the massive work and support on the outside. Sinn Fein was able to turn that into a very narrowly focussed electoral machine which ultimately was only interested in very timid reform within the Six County state, enacting effectively right of centre economic policies. Now that in my opinion is not a success, that element of it is a defeat. Especially since we clearly had the option of a mass movement in the Six Counties and there was a significant mass movement, particularly among the left and the young, in the Republic of Ireland with sizeable sympathy also in Britain.

The British government have been playing a long strategy in Ireland; we are familiar with the terms, normalisation, criminalisation and Ulsterisation dating back to the Labour government of the 1970s. In terms of the current period, where they are clearly trying to normalise British rule – under the so called peace process – how successful do you think they have been?

It strikes me as very abnormal what’s going on just now. For example, in April the British government once again extended for another two years the use of Diplock non jury trials for alleged political offences. There are ongoing abuses in Maghaberry against political prisoners and continued abuses of human rights by the apparently reformed police service who have been using the Terrorism Act stop and search powers – which was found to be in breach of human rights legislation. The PSNI is now using the ‘Justice and Security (Northern Ireland) Act of 2007’, to stop and search and harass nationalists. What does this say to you about normalisation?

The term ‘normalisation’ is defined within parameters set out by the British state. Britain continues to use the north of Ireland as a strategic asset and its game plan in Ireland is related to this strategic interest and over the years this has changed; they have now brought the southern state closer into their orbit, closer now than in any time since the 1922 formation of the state so that counterbalances any potential towards destabilisation in the Six Counties.

You are referring to the recent bilateral loans?

Loans, royal visits, Shannon airport being used by NATO, several endorsements of European Union treaties which now open the door for the south to send troops to join NATO – its not on the horizon next week or the week after, but these things tend to happen slowly and unstoppably and they creep up on us.

North of the border, normalisation has progressed to a certain extent, normalisation within British terms. The big difference now is that a large part of the long term opponent of British rule in Ireland, the republican community, has bought into the arrangement under the auspices of Sinn Fein. Now Sinn Fein has gone a very long way on the road to endorsing policing, and to effectively endorse the union. Because you cannot make the status quo work, and that is what Sinn Fein is dong by working the Good Friday Agreement and by working effectively within the Stormont Assembly and the Stormont Executive, by endorsing all of the machinery that is there, that effectively underpins and underwrites the status quo of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Now there are undoubtedly a minority of Republicans who are very uncomfortable with what’s happening: however they are fragmented at the moment and they differ with a minority within a minority who favour a return to the use of force and a bigger majority who are not advocating the use of force. Some, for the very pragmatic reason that it’s just not feasible. Others taking a more, I would say, orthodox left wing view people like myself who would argue the Leninist case that it is not feasible without mass popular support – and that’s a long, long way off.

That is a destabilising factor. The reality of the situation is, and I would argue that the dialectic of history proves this, that in order to buy out – or to appease Sinn Fein it has been necessary to bring about significant political reform in a situation of economic decline. Northern Ireland no longer provides economic and financial and social benefits to the Protestant working class as it once did. Fifty years ago, the Protestant worker could expect to get first refusal in terms of housing and jobs. And that can be clearly demonstrated just by looking at the statistics. That’s no longer the case. There has been fair employment legislation brought in, housing is regulated along very strict, albeit sectarian lines, but housing is accessible to people at least on a fair basis. And the other thing now is that the huge bastions of Protestant employment have disappeared. Globalisation has taken the ship yards, and the aircraft manufacturing and textiles. What you have at the moment is a very disenchanted and unemployed Protestant working class. Now that does not mean to say that they are drifting towards republicanism or socialism, but they are very unhappy, traumatised and volatile. So for those two reasons, the northern state, which is representative of the British state is maintaining the old organs of coercion, to be used as and when they will need it.

I suspect that there are agent provocateurs at work within the dissident IRA groups. The dissidents seem to materialise at key times, when Sinn Fein need to be reinforced either electorally or in some other sense, and this allows the state to exercise its arms of coercion.

28-day detention was brought in as a result of different situation in Britain but the northern state used it against republicans, some of whom were released without charge. That type of legislation is clearly designed to intimidate, because I don’t see the benefits of it in gaining evidence – if people are not talking to the police after two days its highly unlikely that they will see the light after ten, the only reason that they would after ten, is if its been hammered out of them, either physically or psychologically. The point is that a statement has to be voluntary, that’s the theory – this legislation is turning it upside down.

And we are also seeing other aspects of the coercion of the state in terms of the cancellation of Marion Price’s parole licence for what was at worst a misdemeanour – she held a piece of paper for a man reading out a statement. Now whether she knew what was in the statement or not has yet to be proven. That was the extent of her offence and the state decided to cancel her licence, now that will have an impact on at least 500 people, myself included – I am potentially vulnerable to having my licence cancelled. We are told that the conflict is over and we are in bright new days and that we have all these new benefits. But the British state is happy to go back to the past when it suits it. Normalisation is normal as defined by Britain; it’s not defined by people like me or you.

I want to ask you about Sinn Fein and what social forces they represent in Ireland today? Would it be fair to say that there is a difference to its social base in the north and the south?

Yes, its slightly different north and south. Sinn Fein was traditionally based within the nationalist working class, unemployed working class and rural poor. Now that would remain the Sinn Fein force, but Sinn Fein now expresses the desire to become the main party of the nationalist community. And in the past Sinn Fein would have defined itself very much as republican, it now defines itself as nationalist as often as it does republican. Which up until 25 years ago or 30 years ago would have been a very distinct sharp wedge, between republicans and nationalists who had a very different outlook – now Sinn Fein is moving to encompass them all. And they are now moving to become the party of northern Catholic opinion. By definition that means bringing in the Catholic middle class. What we are seeing is that social forces have changed in Northern Ireland over the past 30-50 years. As a result first and foremost of the civil rights movement of the late 1960s, where we saw the impact of free education acts of the 1940s, brought in by the Labour government. Twenty years later, young Catholic students were emerging from university from families who never would have had an opportunity to have a second level, never mind a third level education – who were then looking for the type of employment that their qualifications entitled them to – only to be closed out because of sectarianism and discrimination. Hence we got these very articulate people emerging.

People like Bernadette Devlin?

Well Bernadette was of the left, many of her colleagues were of the SDLP variety, the school teacher types, who wanted access to employment but not necessarily revolution. They were very comfortable within the SDLP and they led the SDLP – that’s the nationalist conservative party – for the next 20 years. But then the Catholic middle class started to develop, an even more aggressive Catholic middle class – young, educated, confident, capable – who saw Sinn Fein, especially after the ceasefires as a much more competent and useful vehicle. They saw the SDLP as a bit woolly; these guys were much more sharp: Sinn Fein was getting there – doing things, challenging. If you can imagine the type of Labour supporter that you have in the Chelsea area of London. In the old days the toffs, would row boats and go to Ascot, now you get wealthy stockbrokers supporting football, down there on a Saturday watching the big game wearing jeans – class wise they are of the ruling class. Just because they are supporting the football, it means nothing. We are getting that emerging within Sinn Fein who are going for a cross class based approach. The sort of triangulation that Clinton and Blair spoke about, where you have to reach out from your own base and bring in the middle.

Now they are leaving behind those who we could class as the poor, marginalised and disposed, and that is where now you are seeing the dissident IRA emerging – Kilwilkie, the Lower Falls, and so on.

So you think there is a social element to these developments?

Very much so, if you look at where they are strong. Now having said that I am in despair because armed struggle is not the answer, we can’t do it that way. My battle at the moment is to create opposition on the left that is very clear, publically as well as privately, that we cannot under current circumstances resume an armed campaign – we have to fight this on a social basis in order to build a mass social base.

So in the north Sinn Fein is trying to grab middle class and the middle ground. South of the border something roughly similar is happening because of the traumatic experience the population went through as a result of the collapse of the Celtic Tiger. Fianna Fail, the old ruling party, which had effectively been the ruling party for 80 years, was rightly and understandably hammered at the polls by the electorate. Sinn Fein was able to make considerable gains as a result for a number of reasons. Fianna Fail had achieved a position where, not unlike the current situation facing Sinn Fein in the north, its old base was the urban working class and the poorer of the rural agricultural population. It was one of the big problems of the left in Ireland and Dublin in particular where the Labour party went far to the right – and held a small section of working class support – Fianna Fail were in many ways a much more social democratic Keynesian type of socialism during the 1930s and 40s. Those working class people were also republican and there was a very significant number of them in Dublin, they were very hostile to the Labour party so we didn’t get the emergence of a Labour party as we saw in Britain.

I would have thought given the crisis, the effective bankruptcy of the state, with the IMF coming in, the situation would have been ripe for Sinn Fein to campaign on a left wing socialist agenda?

They didn’t; they should have. Sinn Fein ran with a number of populist policies, one of which was ‘burn the bond holders’. There is a guy called Constantin Gurdgiev a right wing Russian economist lecturing at Trinity College, Dublin – unapologetically neo liberal and he along with another guy called David McWilliams, another right wing economist are also calling on the bond holders to be burned.

There is nothing radical about it, what they are saying is capitalism my friend is governed by the market, and if you invest unwisely and lose your money, then tough cheese mate. And that’s what Gurdgiev and McWilliams are saying, that our state should have said tough cheese, but they also want us to work harder for less money in order to make us competitive and the poor have to take their place, they are neo-liberals.

In regard to the recent election in the south, there was the emergence of this new coalition called the United Left Alliance, a coalition of different left groups who came together for the purposes of the election – they had a progressive programme insofar as they called for the defence of jobs and opposition to the bank bail outs. But there was also a critique put forward by some on the left, most notably the Irish Republican Socialist Party who noted the absence from their programme of them actually saying they were socialists or arguing explicitly for socialism, and interestingly they avoided the national question in relation to the north and they avoided any question of imperialism. Now given the most recent developments, the bilateral loans from London to Dublin, the IMF coming in, European subsidies to Ireland and the use of Shannon airport by the US military as a strategic base, I would have thought, that the anti-imperialist position would be a valid one.

It would be an obvious one; in fact that would essentially be the critique that I would make of that group. But at the same time I have to look at it from a practical point of view, we of the left have a challenge, we must persuade those people. My view is that they are mistaken, but they are not our enemy. Fianna Fail and Fine Gael are also mistaken, but are clearly our enemies. I have no common ground with them. Now, you are correct that, the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and the Socialist Party (SP) and a number of left leaning independents formed that United Left Alliance, and did quite well in the election. As for their programme, and this is perhaps the real critique of it, their programme was aimed at the middle class – those that had a large mortgage and were afraid of losing it, and they were not putting the position clear and simple that the system is incapable of reform.

The SWP and SP have a mistaken view that British imperialism and loyalism in the north of Ireland can be appeased via class politics. They ignore the national question and the imperialist question in order to concentrate on class politics, I believe that they are living in Cloud Cuckoo Land. Let’s take an example, about two years ago the Royal Irish Regiment, which is a regiment of the British Army was coming back from a tour of duty from Afghanistan, for a victory parade through Belfast. The eirigi group in Belfast, which was quite small, approached the SWP and SP to call for an anti-war protest, and they were prepared to broaden it out so it was not just an anti-British Army protest or a republican protest. The two are not necessarily hostile to one another, but there is a difference. Eirigi were saying we are happy to fall in behind you and make this an anti-Afghanistan and Iraq war protest, the SWP and SP said no, no, that would be misunderstood as the Protestant people would not understand that. And as the eirigi folk were saying at some point you’re going to have to tell them the truth boys, you can’t keep on waiting for the great day. So the protest was carried almost alone by eirigi and of course once eirigi called a protest then Sinn Fein sent a few along on the purely Irish republican basis of protesting against the British Army. That is the real problem.

In the 1920s, after the civil war, the Labour Party went with the right wing. This led the origins of Fianna Fail to have a hold over significant sections of the working class in Dublin. And that division remains; our difficulty here is that if we are not able to bring in the radical republican constituency and fuse it with the radical and genuine left, and until the United Left Alliance starts to understand the need for republicans and left republicans to be brought on board, otherwise they are going to lose out to Sinn Fein who will eventually bring it into reformism and an accommodation with the status quo.

What class forces does the United Left Alliance represent? Do they actually represent any working class interests? Or have a base among ordinary people?

I wouldn’t be totally dismissive of them. For the most part they are a middle class organisation the United Left Alliance. Now having said that Joe Higgins of the SP was able to get one out of three seats in Dublin, so it wasn’t an exclusively middle class vote for Joe Higgins. Fine Gael and Labour also got seats, so there must have been working class people voting for Joe Higgins. The problem were having with the United Left Alliance is that getting right down to representing working class interests, the problem I would argue with so many of the Trotskyist groups, is people coming in from beyond the working class believing that they can interpret what the working class needs. It’s an old problem with Trotskyism for many, many years and it remains.. They hold on to bourgeois instincts, that they think of themselves as so much superior in many ways, its almost as if they are a religious sect, where they alone have the answers in some sort of bible.

There is no problem making a critique of republicanism and finding right wing tendencies and opportunistic tendencies. You can find that in practically every political grouping in the world. I remember being at a meeting in Derry City a couple of years ago commemorating 1969 with Bernadette McAliskey. The meeting had been organised largely by the SWP and Bernadette quoted a line from Lenin, after the April uprisings, and Lenin said it was better to go down to the feet with the people than stand on the sidelines from their struggle. Whether you believe they made the right move at the right time or not. And Bernadette said that’s why she did not join the Provisionals but did support the people in their struggle against the British. The SWP have found all sorts of agonising ideological reasons for disserting the flag.

Turning back to the north, and looking in particular at its economy, given the overall crisis and the need for imperialism to undermine social welfare, there is a great need for them to reduce the state subsidies to the public sector. But without these subsidies, from an economic point of view we can say that the north of Ireland is a completely unviable economic entity.

Northern Ireland is an utterly and absolutely an unviable economic entity – as structured at the moment, due to the fact we are peripheral region of the United Kingdom and we are tied into the overall European Union and we have been victims of globalisation and the crisis of capitalism. At the moment the north of Ireland is now suffering the additional problem in that the Scottish Office and the Welsh Office and people in the north of England are asking why, Northern Ireland should be receiving such subsidies in terms of housing and education, per capita, while we here in Glasgow or we here in Cardiff aren’t getting this. A perfectly good argument if we are all supposed to be part of the United Kingdom. While the troubles were going on, it was always possible to turn round the Secretary of State for Scotland and say listen – how many members of the Black Watch do you want killed? Let’s give them a few bob, keep them quite, and keep our Scottish soldiers safe. That doesn’t pertain any longer. So now you’re back to the argument about parity right across the board from the north, to Scotland to London.

In terms of attracting Foreign Direct Investment, they are now proposing to lower the rate of corporation tax, which is one of these great shimmers that daft economists come up with, saying if we lower the tax rate all these great companies will flood in to the north of Ireland. One or two might well, but recently the only companies which have come to Northern Ireland have been call centres, operating on the minimum wage. (Many people in Britain or the US prefer to hear a northern Irish accent than an Indian or Pakistani accent, and that’s just down to naked racism, which never worries capitalism obviously.) With the minimum wage, you’re bringing in an educated population and your sweat-shopping them. So it’s not a great industry, and even they are now going.

In my opinion there are only two ways the northern Irish economy can go. Either you follow a different model of capitalism – you break free, set up your own tax rates and currency and you turn it into a brothel, with gambling and off shore accounts, banking and so on. Or you look to build a planned economy, a completely different system which would bring us into socialism.

So long as we are on the periphery of the United Kingdom and subject to what is good for the City of London, and nobody there gives a fiddlers about the Outer Hebrides or Fermanagh. And as long as we are under capitalism that will always remain the case.

You described republican militant activity as having a ‘destabilising effect’, how significant do you think this has been in terms of undermining the attractiveness for capital to invest in the north?

In some ways it does, but the intensity of the campaign is not sufficient enough to put off capital. Capital will always be protected, and the state will put its forces around the factories if need be and they will ensure and assure the investors that their interests will be protected come what may and they will do this quite successfully. That’s one thing.

But it’s a two-edged sword in terms of destabilisation. To a certain extent the dissidents are actually solidifying the state. They don’t have the military capacity to overthrowing the institutions, but they give Sinn Fein scope to cuddle up to the police, the DUP and the organs of the state.

The bottom line is, among the republican community after 25 years of intense insurrection, in a small area, with a small population, there is no appetite for a return to war.

Can I ask your view on the political purpose of these inquiries which are taking place into Britain’s war in Ireland? It has been one of the key tenets of Sinn Fein’s involvement in the political process, and also victims of state terror to call for these inquiries: the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Rosemary Nelson Inquiry etc. We also had recently increased calls for inquiries into the murder of Pat Finucane, the events at Loughgall and other instances of Britain’s shoot to kill policy in Ireland.

Peter Cory, the retired Canadian judge made a number of recommendations that inquiries should take place made it clear in a letter he wrote in 2005 that when the Labour government repealed the 1921 Public Inquiry Act and replaced it with Inquires Act 2005 it greatly restricted the capacity for any of these inquires to do anything and allowed those being investigated to ‘thwart the enquiry at every step’.

The so-called peace process was a carefully choreographed piece of work to bring different sections on board. Britain had identified its ideal solution early on, in the early seventies. By the time we had got to the nineteen nineties, and we had the ceasefires and so on, and they had brought people on, they knew the outline of the structure they wanted.

The inquiry which really should be taking place is into why the hell the British insisted in doing what they did, in behaving criminally in Ireland in 1968. Why, when they knew exactly what was going to happen, did they not take the steps which would have been necessary to forestall and prevent. And the reason, very simply is Britain had and has a strategic interest in the north of Ireland and the only reason it could claim to stay there was with the permission of the unionist majority, once unionism withdraws its consent to the union the union collapses, that’s obvious.

In the late 1960s there was a fear of unilateral declarations of independence, as similar to Rhodesia hanging in the air. There was a very significant move in northern Ireland towards that if Britain displeased them. Bill Craig, the Minister for Home Affairs had big 50,000 person rallies in Ormeau Park his two most able lieutenants at the time were David Trimble, and Reg Empey, the last two leaders of the Unionist Party. This was no insignificant move.

So Britain could do the right thing, by democracy in ’68 and ‘69 and lose the support of the unionists, or it could soft-peddle and push democracy to one side for the republicans and nationalists and give tantamount support to unionism and that is what happened. And now Britain wants it to be brought down to ‘yes, we made some mistakes, we shot the wrong people on Bloody Sunday, yes, we may have made a mistake when we shot a wee girl with a plastic bullet’. But they are not saying why their campaign, why their presence, their occupation and imperialist desires were wrong. They pick two or three incidents, so they concede they did do wrong on Bloody Sunday and they blame the officers, they didn’t blame the state, they didn’t blame the Parachute Regiment as a whole, they blame a few bad apples. And they cherry-pick a few incidents so Sinn Fein can say to the nationalist and republican community that we had a wonderful outcome from the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, and isn’t it marvellous that the British Prime Minister apologised for what his troops did in Derry that day. But what we are not hearing is ‘we should not have done what we did over the last 50 years because our position was one of naked imperialist aggression’.

They are taking us in the wrong direction. We spend ten years and millions finding out what happened in Bloody Sunday or with Rosemary Nelson and it’s a qualified apology. They are saying there was obviously no collusion, and what we get is this notion of police officers offering less than best practice. We will wait possibly another six years and hear in relation to Pat Finucane that yes a policeman gave the UDA the gun, but unfortunately that policeman died two years ago. But the state did not do it, it was a bad apple.

Can I ask you about this question of opposition to Orange parades, and we know there is some opposition in areas like Ardoyne, and Lurgan and Derry and elsewhere, last year the nationalist residents came under attack not just from the state and the media but also from Sinn Fein themselves – Gerry Adams describing those residents opposed to the loyalist incursion in Ardoyne as ‘anti social and criminal elements’ and Martin McGuiness claimed that they were ‘Neanderthals’.

Always the point about it is, protest is permitted so long as it’s ineffective. And if there is any chance of it becoming effective then it is then criminalised. Its carefully chosen language, Sinn Fein doesn’t make public pronouncements by accident, it’s very careful. Sinn Fein has become a party of the establishment; there is no question about that. And Sinn Fein is now totally supportive of policing, which on a very broad Marxist basis, I find it, well not surprising that Sinn Fein would do it, but I would oppose policing by that state anyway. My question is when will they stop arresting secondary and sympathetic picketers – when they stop doing that, and a lot of other issues, then I will maybe consider my position. Because I don’t even have to look at things like Orange parades, they are part of the state which I don’t support. Sinn Fein are part of that establishment, and the thing about it is there are very, very few contentious parades in Northern Ireland. If we were talking about a situation of widespread tolerance and acceptance by the Orange Order – which would be ironic, because the Orange Order is there to be provocative, to be dominant and to reinforce a particular type of superiority, so when it stops doing that it will stop being the Orange Order, it will have no role in the world.

But having said that, why after all these years where it has done all that – I believe that the onus should not be put on the people of Ardoyne, the onus should be put on the Orange Order to say why they should march past the people of Ardoyne, rather than the other way around, on people who have been subjected to this torment and racist, sectarian behaviour for so long. This is like asking the black people of Alabama to be more tolerant of the Klu Klux Klan marching down their street, although you could conceivably say that the Klan will be well marshalled and that they won’t be playing their tunes, and that they might just walk by the end of one of the streets occupied by the Afro Americans. But at the same time, the onus should not be on them, just as the onus should not be on the republican people of Ardoyne to accommodate this.

Tommy McKearney’s new book The Provisional IRA: From Insurrection to Parliament is due to be published in August by Pluto Press.