The announcement that Tony Benn has been invited to speak at a Sinn Fein conference in London on 18 June commemorating the 30th anniversary of the 1981 Irish hunger strike is an insult to the struggle of the Irish people. Benn’s record during this period was one of unstinting support for British imperialism. He was a member of the Labour government whose strategy of criminalising the Irish liberation movement precipitated the prisoners’ struggle for political status and eventually led to the hunger strike. Not once during this period did he attend a demonstration in support of the Irish prisoners, not once did he stand up for them in public.

It was a Labour government that originally sent troops into the north of Ireland in August 1969. As a cabinet member at the time, Benn did not oppose this. He went on to be a cabinet member throughout the 1974-79 Labour government, where he did not oppose the Prevention of Terrorism Act, which Labour introduced in December 1974, the purpose of which was to terrorise Irish people in Britain. He remained a member of that Labour government as it sought to criminalise the Irish freedom struggle by withdrawing Special Category status from political prisoners in May 1976 and building the notorious H-blocks. A regime of arbitrary detention and torture was put in place and jury-less Diplock Courts were used to rubber-stamp confessions beaten out of suspects. Neither the murder of 10 people in an SAS shoot-to-kill campaign in 1977-78 nor an Amnesty International report exposing torture in the north were sufficient to move Benn to resign from the government.

The first prisoner to be sentenced after withdrawal of political status was Kieran Nugent. He refused to wear prison clothes and perform prison work. From this grew a mass movement in republican areas of the north of Ireland in support of the prisoners’ demands. Not that this was of the slightest concern to Tony Benn as he carefully cultivated his left-wing image following Labour’s general election defeat in 1979. In March 1980 he participated in what some called the ‘Debate of the Decade’ with Tariq Ali, Hilary Wainwright (editor now of Red Pepper) and the SWP’s Paul Foot. As Tony Benn rose to speak, Hands off Ireland! supporters unfurled a banner behind him asking ‘Are you with Benn or the H-Block men?’ As FRFI reported,

‘…Benn was forced to state that while he believed in the unity and independence of Ireland he did not support the withdrawal of British troops. He refused to say one word about the H-Blocks. Hands off Ireland! thus exposed Benn for the pro-imperialist he is. But his fellow ‘debaters’, the Paul Foots and Tariq Alis, themselves kept silent on H-Block and made no attack on Benn for his anti-Irish statements. To have done so would have destroyed their long-sought alliance with Benn.’ (FRFI No 4)

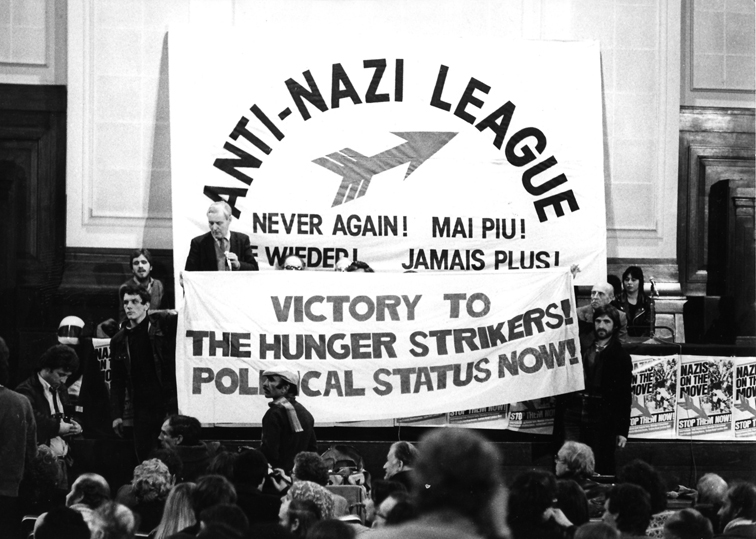

On 8 December 1980 the Anti Nazi League held a rally against fascism with Tony Benn on the platform. Revolutionary Communist Group (RCG) members stood in front of Benn displaying a large banner saying ‘Victory to the Hunger Strikers! Political Status Now!’ Heckled from the floor, Benn once again refused to offer support to the prisoners. As the prisoners’ struggle intensified during 1980, in Britain the opportunists launched Charter 80, a campaign which supported five demands in a plea to make prison conditions more humane, but which rejected open support for political status. It made clear that it was asking for support ‘irrespective of whether you support the prisoners’ actions, ideology or political affiliation.’ In other words, it was to be separated from any support for Irish liberation. Backers included forces completely hostile to the Republican movement: the Communist Party of Great Britain, the Young Liberals and various Labour lefts including Benn. This was to be his sole gesture on the prisoner issue.

On 27 October 1980, seven Republican prisoners began what was to be the first of two hunger strikes. Such a desperate action was the outcome of the failure to create a movement which could challenge the intransigence of the Thatcher government. In the newly-established Hunger Strike Coordinating Committee the RCG argued that those Labour MPs who had signed Charter 80 should be invited to attend a demonstration outside Parliament which the Committee had organised. The rest of the left rejected this, on the grounds that ‘the RCG put the proposal only with a view to “exposing” Tony Benn and the Labour lefts’. This was nonsense: a public stand by Benn and other Labour MPs could have made a real difference. They never made such a stand.

Benn himself had a great opportunity to give a lead at the 1980 Labour Party conference. Yet when the conference debated Ireland, Benn and the rest of the Labour left kept their mouths firmly shut. In his main speech to the conference, Benn set out what he envisaged the next Labour government would do. ‘Within days’, a Labour Government would grant powers to nationalise industries, control capital and implement industrial democracy; ‘within weeks’ all powers from Brussels would be returned to Westminster; then they would abolish the House of Lords by creating one thousand peers and abolishing the peerage. Benn received tumultuous applause; Paul Foot declared ‘there can hardly have been a socialist in Britain who did not feel warmth and solidarity for Tony Benn’. Yet there was no room for Ireland and the prisoners in Benn’s torrent of radical phrases or in his shopping list of early actions a Labour government would take.

In the face of enormous protests in both the north and south of Ireland the Thatcher government felt that conditions were not yet right to defeat the liberation struggle, and offered sufficient concession for the prisoners to call off the hunger strike on 18 December. Left Labour MPs who had kept silent for the first seven weeks of the strike issued a statement in the eighth week calling for a ‘humanitarian’ approach to the prisoners, saying that any deaths would ‘strengthen the hand of all those who favour force rather than democratic political campaigning.’ (FRFI No 8)

When the Thatcher government refused to honour its commitments to the prisoners, the prisoners decided that there was no alternative but to start to a second hunger strike in March 1981. Benn remained silent throughout. By the time the hunger strike was called off on 3 October 1981, ten prisoners had been murdered. In Britain, the opportunist left had run for cover rather than take a stand against the British state. Throughout the period the RCG and its publications Hands off Ireland and Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! took a principled stand, with supporters building demonstrations, organising pickets, street events and public meetings calling for political status. In the face of repression by the police, physical attacks by fascists, and political isolation by the opportunists, where it could it built support groups which were the most active in the country, particularly in Glasgow, where they were able to create an alliance with sections of the republican working class. This showed that a movement could be built; the opportunist left made sure it wasn’t.

In the intervening years Benn has attempted to cover up his abject behaviour. The Times, among others, reported in August 2008 that he ‘broke down in tears at the Edinburgh Book Festival as he recalled the late Bobby Sands… “Our revenge, Bobby Sands said, will be the laughter of our children,” he said, as tears began to stream down his cheeks. “I’m sorry, but it moves me greatly.”’ Maybe it moves him in retrospect: it certainly did not move him at the time, when he could have made a difference. However, he had made his choice: to remain a member of the imperialist Labour Party and therefore be complicit in the oppression of the Irish people and the murder of the hunger strikers. He should be reminded of this on 18 June.

Robert Clough