Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! no. 11, July/August 1981

Imperialist exploitation over the whole of Ireland is maintained through the partition of Ireland. To secure Partition, British imperialism created in the six north-eastern counties of Ireland a reactionary loyalist police state. This state is based on the denial of basic democratic rights of the minority nationalist (Catholic) population in the Six Counties. Inevitably, the next major stage of the struggle for a united Ireland was to centre on this British-imposed loyalist statelet. And it was the struggle of the minority nationalist population for basic democratic rights in the late 1960s which laid the foundation for the re-emergence of revolutionary nationalism as a mass force in the six north-eastern counties of Ireland.

However, from the ending of the civil war (1923) until the late 1960s, the social and political conditions did not exist to unite a mass movement behind a military and political campaign to defeat British imperialism. Nevertheless, in its efforts to keep the revolutionary tradition alive and an armed organisation intact, the IRA was to carry out two military campaigns – the first in England (1939-40) and the second in the Six Counties (1956-62).

The campaign in England 1939-40

Towards the end of the 1930s, the IRA sought to rebuild active support for the Republican Movement and decided to resume its military offensive against British imperialism. Preparations and training for a bombing campaign in England began in 1938. It was to be accompanied by a military campaign in the North, but in November 1938 three IRA men were killed on a mission to bomb customs posts when a faulty mine exploded in a house they were in near the border. This accident and some successful demolitions of customs posts increased RUC-Special Branch activity in the North. In December, 34 IRA men in the North were arrested and interned. This was to rule out any serious campaign in the North; however, it had little effect on the English campaign.

On 12 January 1939, the IRA delivered an ultimatum to the British government demanding the withdrawal of all British armed forces and civilian representatives from every part of Ireland. If the government refused, then the IRA would be ‘compelled to intervene actively in the military and commercial life of your country as your Government are now intervening in ours’. The British government were given four days to respond. On 16 January 1939, the bombing campaign began with seven explosions in three centres, London, Birmingham and Manchester. The aim was sabotage of basic installations such as electricity, gas, water supplies and train services. By July, there had been 127 explosions and many Irishmen and women had been rounded up, arrested and convicted.

On 24 July, the government introduced an anti-Irish Prevention of Violence Bill with sweeping powers to demand the registration of all Irish people in Britain and to deport Irish citizens at will. The Bill was passed in five days – its modern equivalent, the Prevention of Terrorism Act, took less than three – and within a week 48 people had been expelled from Britain and five prohibited from entering Britain.

IRA volunteers were ordered to make every effort to avoid civilian casualties but in the course of the campaign civilians were injured and some were killed. On 25 August in Coventry, a bomb being taken by bike to a generating station blew up prematurely, killing 5 people and injuring over 50. The police went through every Irish home in Coventry. Two men, Peter Barnes and James McCormack, were eventually arrested, and on very slender evidence were tried, convicted and executed. Barnes and McCormack, while IRA volunteers, had no direct responsibility for the Coventry explosion. But the British, as always, when dealing with the Irish, have never been in the slightest concerned with justice.

The judicial murder of Barnes and McCormack was not the only blow struck against the IRA and its supporters during the campaign. In England, 23 men and women were sentenced to 20 years in prison for their involvement in the campaign. 34 to 10-20 years, and 14 to under 5 years. In the 26 Counties of Ireland, the Fianna Fáil government stepped up its repression of the IRA and its supporters. In June 1939, the Offences Against the State Act was passed and over 50 IRA men were interned. In April 1940 in Mountjoy prison, two IRA volunteers, Tony D’Arcy and Jack McNeela, died after a long hunger strike to demand treatment as political prisoners.

Faced with such blows and set-backs, in March 1940, the English campaign – the IRA’s first major military effort since the Civil War – came to an end. It would take some time before the IRA would be able to rebuild its organisation and resources and gather together the necessary support to conduct another military campaign against British imperialism.

The response of the British Labour and socialist movement to the IRA campaign followed what was by now a familiar pattern. The violence, brutality and injustice of British imperialism, if opposed at all, was only opposed on the grounds that it created support for a revolutionary opposition to imperialism among the oppressed. The real hostility, however, was usually reserved for the revolutionary forces fighting British imperialism.

The argument always contained some hollow gesture of support for a united Ireland. But invariably, it condemned those actually resorting to force to obtain it. So, at the time of the debate on the Prevention of Violence Bill, Arthur Greenwood, the Labour MP, could say:

‘Terrorist methods . . . would achieve nothing . . . Many MPs on both sides of the House would like to see a united Ireland, but the way a minority had chosen would defeat its own object . . .’ (Daily Herald 25 July 1939)

However, if the minority uses force, the Labour Party made it clear that it must be put down:

‘Believing that IRA terrorism must be stopped, the Labour Party will not vote against the IRA Bill which is to be debated this afternoon and rushed through all its stages by Wednesday night . . .’ (Daily Herald 24 July 1939)

There was some concern (amendments were proposed) that measures taken against the IRA might go too far and ‘do violence to the liberties of the law-abiding British subject’. And that widespread repression could stir up much wider opposition to British rule in Ireland. So, Wedgewood Benn (the father of Anthony Wedgewood Benn) warned the government:

‘If you punish an innocent man, your quarrel will not be with the IRA, it will be with Ireland, and you will stir up the hatred of Irish Americans.’ (Daily Herald 25 July 1939)

That even these qualifications did not go very far in the Labour Party was shown when only 17 Labour MPs voted against the anti-Irish Prevention of Violence Bill. And Wedgewood Benn was not included among them. Their overriding concern was clearly to crush any support that existed for the IRA.

The Communist Party reported the bombing campaign with little or no comment. But an editorial on the Prevention of Violence Bill showed a significant change of position from that held by communists at the time of Partition. The Communist Party opposed the Prevention of Violence Bill on the grounds that it would be used as an excuse to attack British liberty. But they had no qualms about the police attacking the IRA:

‘It is wrong to describe this measure as an anti-IRA Bill. It uses the bombing activities of the IRA as an excuse for attacking British liberty . . . Will they (the police) know the difference between those who support an Irish Republic and the small group who are mis-using the historic name of the Irish Republican Army . . .’ (Daily Worker 26 July 1939)

Later, in an editorial opposing the forthcoming executions of Barnes and McCormack, the main features of the new position became clear. The Communist Party, while ‘understanding’ the motives of the IRA condemned its actual struggle to achieve a united Ireland:

‘We are against terrorism in politics and we have condemned the IRA bombings. But we understand the motives and the principles which actuate these Irish patriots. They want their country to be free, independent and united.’ (Daily Worker 3 February 1940)

Did this mean that the Communist Party which recognised that Ireland had been divided by the force of arms would no longer defend those committed to unite Ireland by the force of arms? What was clear was that the new position was a reactionary one. Real communists would after all have opposed, without any qualifications whatsoever, both the execution of Barnes and McCormack and the Prevention of Violence Bill. And real communists would have stated that the responsibility for any injuries and deaths during the campaign lay with British imperialism.

The Border Campaign 1956-62

It took 16 years before the IRA had the resources and organisation to launch a new military campaign against British imperialism. This took place in the Six Counties and was concentrated on the border.

At Bodenstown in 1949, the IRA made a declaration that force would no longer be used against the 26 Counties Irish government but only against the British forces of occupation in the Six Counties. It was thought that this position, formally incorporated into ‘General Army Orders’ in 1954, would induce Dublin to tolerate the campaign and the use of the 26 Counties as a staging post for their actions in the Six Counties. This was to prove a major miscalculation.

Plans for a campaign were drawn up in 1951. The first steps towards getting the campaign underway consisted of raids on British military barracks and armaments depots to obtain additional supplies of arms and ammunition. A very successful raid occurred in 1951 at the Ebrington Territorial Barracks, Derry. The haul included 20 Lee Enfield rifles, twenty STEN guns as well as a number of machine-guns. Two raids in England failed, one at Felstead, Essex in 1953 and the other at the Arborfield Depot, Berkshire in 1955. In both cases large hauls of arms were taken but in each case the vehicle carrying the arms was stopped by police and the arms were captured before they could be got away. As a result of the Felstead raid, Seán Mac Stíofáin, Cathal Goulding and Manus Canning were arrested and imprisoned for 8 years. After being sentenced, Cathal Goulding, on behalf of the other prisoners, declared:

‘We believe that the only way to drive the British Army from our Country is by force of arms, for that purpose we think it no crime to capture arms from our enemies.’

The most successful raid, which aroused considerable support and new recruits for the IRA, was that at the Gough barracks, Armagh, in June 1954. There the haul included 340 rifles and 50 STEN guns. A few more largely unsuccessful raids were to take place before the commencement of the campaign. 8 men were arrested and given long prison sentences as a result of the raid at the Omagh military barracks in October 1954. Those imprisoned rapidly gained support amongst the nationalist population for both the daring character of the raid itself and their principled conduct during the trial.

A Westminster election was called in May 1955. The IRA, through Sinn Féin, decided to contest the elections on an abstentionist platform and show they had a popular mandate for the coming campaign. They named candidates for all twelve seats, half of them prisoners who were in jail for the Omagh raid, and made it clear that they would not stand down for anyone. The bourgeois Nationalist Party, a nominal ‘opposition’ in the Six Counties loyalist parliament, were faced with a dilemma – much like the SDLP in the election of Bobby Sands and Owen Carron during the current hunger-strike campaign. Running a candidate against Sinn Féin would split the nationalist vote and allow the Unionists to win. If that happened, and with the likelihood of them getting a much lower vote than Sinn Féin, the Nationalist Party would rapidly lose any of the support they still had. They decided it was better not to stand especially after Phil Clarke, nominated by Sinn Féin, had been selected as nationalist candidate for Fermanagh-South Tyrone in preference to Cahir Healy, the Nationalist Party MP. During the fight for the nomination, Cahir Healy had denounced the policies of ‘physical force’ and ‘abstentionism’.

Sinn Féin obtained a total of 152,310 votes in the election and won the two nationalist seats of Mid-Ulster and Fermanagh-South Tyrone. It was the biggest anti-partition vote since 1921. Sinn Féin had won the allegiance of the nationalist population on a platform stressing only the national issue and with candidates who supported the armed struggle of the IRA. This vote reflected the growing hostility of the nationalist population to the openly repressive loyalist police state.

Since the candidates elected, Tom Mitchell for Mid-Ulster and Phil Clarke for Fermanagh-South Tyrone, were ‘convicted felons’, both serving sentences for the Omagh raid, under British ‘democracy’ they were ineligible to be elected and to hold their seats. The defeated Unionist candidate in Fermanagh-South Tyrone filed an election petition in June to have Clarke unseated and himself declared elected. This eventually occurred after the defeat of a small opposition to it in the Westminster parliament led by the Labour MP Sidney Silverman supported by some left-wing Labour MPs. So much for parliamentary democracy.

As no petition was filed, the seat in Mid-Ulster was declared vacant and a by-election called in August 1955. Tom Mitchell ran again and was elected with an increased majority over the Unionist. He was again disqualified but it was found that the Unionist candidate was ineligible to take his seat because he had held an ‘office of profit under the Crown’. A third by-election was held in May 1956 and this time the Nationalist Party stood a candidate. Tom Mitchell stood again and won four times as many votes as the Nationalist Party candidate – the latter losing his deposit. But the Unionist won the seat as the nationalist vote had been split. No-one could doubt, however, where the sympathies of the nationalist population lay. British imperialism had shown time and again that it would never voluntarily heed the democratically expressed wishes of the nationalist population. British imperialism had only ever been moved when confronted by revolutionary force. The outcome of the election, therefore, showed that there would be support among the nationalist minority in the Six Counties for the military campaign planned by the IRA.

At the beginning of 1956, a plan of campaign ‘Operation Harvest’ was drawn up by Seán Cronin. The plan was to attack the North with the aim of destroying installations and public property on such a scale as to paralyse the Six Counties. The campaign aimed to use the methods of guerrilla warfare ‘within the occupied area’ and as support built up to liberate large areas ‘where the enemy’s writ no longer runs’. The plan, a version of which was captured by the security forces in January 1957 after a raid, was considerably modified in practice.

The IRA decided to avoid action in Belfast because it was felt that this might provoke a loyalist backlash and lead to attacks on the nationalist areas. There was some dispute within the IRA as to whether they would have the resources and organisation to defend the nationalist areas in Belfast. And the arrest of the Belfast organiser before the beginning of the campaign finally decided the issue. But this indicated a problem for a campaign which had the aim of paralysing the Six Counties. Belfast, the political administrative and economic centre of the loyalist state was to be left alone.

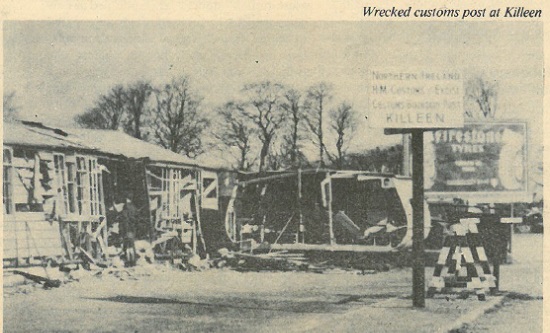

There was a great deal of pressure within the IRA to launch a military campaign in the Six Counties. In 1951, Liam Kelly had been expelled for taking unauthorised action. He took most of the eastern Tyrone organisation with him and soon set up a new armed organisation, Saor Uladh. In June 1956, Joe Christle, a militant IRA member impatient with the lack of action, was expelled from the IRA and he took most of the young Dublin activists with him. His group and Saor Uladh were to link up in September 1956 and were to carry out a number of combined attacks on customs posts on the border in November 1956. These developments no doubt enabled those in the IRA leadership wanting to launch the military campaign to win the argument over their more cautious comrades.

The campaign began on the night of 11-12 December 1956. About 150 men blew up targets in the Six Counties around or near the border area: a BBC transmitter, a barracks, a territorial army building, a magistrates’ court, and a number of bridges were damaged or destroyed. The response of the loyalist government was immediate. It introduced internment and more than 100 northern IRA men were rounded up. By 1958, nearly 187 were held. ‘Unapproved roads’ in border areas were blown up by British army sappers and bridges were destroyed. 3,000 RUC men and 12,000 B-Specials were called into action and were joined by British Army Scout cars. The North was turned into an armed camp. South of the border, the number of guards doubled and the Gardaí continually harassed and arrested IRA men. On 16 December, the Gardaí arrested part of the IRA Army Council and eleven other members of the IRA. They were, however, this time released the same day, but the signs were ominous.

On New Year’s Eve two RUC barracks were attacked in Fermanagh, and during the attack at Brookeborough two IRA men were killed. The two men, Sean South and Fergal O’Hanlon, became national heroes in the 26 Counties and thousands attended their funerals some 50,000 following Seán South’s funeral in Limerick. There was an up-surge of support for the IRA, and much resentment when the Taoiseach John Costello, head of the coalition government in the South, in January 1957, had most of the IRA Army Council rounded up and jailed for short terms under the Offences Against the State Act.

On 28 January 1957 Seán MacBride, the leader of Clann na Poblachta, a party with Republican sympathies, which had joined the coalition government, was forced by rank-and-file pressure to move a vote of no confidence in the government. This was both on economic grounds and its failure to pursue a positive policy on the reunification of Ireland. It was precipitated by the government’s continual harassment of the IRA. The Government was defeated and the Dáil dissolved. A new election took place on 5 March. Fianna Fáil was returned with a clear majority. De Valera was now back in power.

For the election, Sinn Féin nominated 19 candidates, many of them prisoners, campaigning solely on the national issue and on an abstentionist platform. Four were elected and Sinn Féin received 65,640 votes – the highest total they had received in the South since 1927, about 6% of the total vote. However this was to represent the high point of support for the Republican Movement during the Border Campaign.

Fianna Fáil under de Valera had little or no inhibitions about suppressing the IRA. Besides, the economy was in difficulties, unemployment having reached 70,000 and emigration at its highest point since the 1880s. De Valera needed to improve trading relations with Britain and quite clearly wasn’t going to let the IRA get in the way. On 6-7 July 1957, soon after an IRA ambush of a RUC patrol in Co Armagh, internment was reintroduced in the South. All the Sinn Féin Ard Comhairle (national committee) except one, most of the Army Council and GHQ staff and many IRA men in the country were soon in the Curragh internment camp. It was a crushing blow. However, the IRA infrastructure in the Six Counties, hardened by coercion, still existed and functioned. But any idea of escalating the campaign was now ruled out. The campaign never regained the momentum of the initial attack. While in the first month of the campaign, December 1956, there had been 25 operations and in 1957 a total of 341, during 1959 there were only 27 incidents and in 1960 there were 26. Support for the IRA gradually fell away. In the October 1959 Westminster elections, Sinn Féin contested twelve seats, won none of them and received less than half the votes they obtained in 1955. In October 1961, there was an election in the South and Sinn Féin lost all four seats they won in 1957, their vote dropping to 36,393. The arrests, internment, repression and increased security had taken their toll. Political backing for the campaign now was down to the hard Republican core. The campaign had to be called off.

The IRA Army Council ordered their volunteers to dump arms on 26 February 1962. In a statement on the ending of the campaign it said:

‘The decision to end the resistance campaign has been taken in view of the general situation. Foremost among the factors motivating this course of action has been the attitude of the general public whose minds have been deliberately distracted from the supreme issue facing the Irish people – the unity and freedom of Ireland.’

That is, the campaign had to be ended because of the falling away of support. During the campaign, eight IRA men and one sympathiser, two Saor Uladh members, and six RUC men had been killed. Outright damage in the Six Counties was assessed at £1 million and the cost of increased police and military patrols at £10 million. But the campaign had failed. Stormont had hardly been touched.

Why did the campaign fail? Was the IRA finished? Could the revolutionary armed struggle to drive British imperialism out of Ireland ever succeed? These were questions being asked both inside and outside the Republican Movement after this defeat. The answers given to them were to have important repercussions in the movement over the next ten years.

There were many who put down the defeat to the IRA/Sinn Féin concentration on the armed struggle and the failure of the Republican Movement to take up broader ‘economic and social issues’. That is, in the terms of those who argued in this way, the failure of the IRA to become more ‘political’. Those arguing this position in the Republican Movement were to become the dominant trend over the next seven years with near disastrous consequences when the next phase of armed struggle began.

A typical ‘left-wing’ analysis of the defeat along similar lines is expressed by Michael Farrell, a leading member of People’s Democracy (now part of the Fourth International) and a Trotskyist. He argued that the IRA’s explanation of the defeat was inadequate. They could not simply ‘blame the people’ for not supporting them. The failure of the 1956-62 campaign, according to Farrell, was due to the fact that:

‘. . . the IRA was in possibly the most unpolitical phase of its history . . . and the IRA, while despising parliamentary politicians, was deeply suspicious of left-wing politics. They had no policy other than physical force and no serious political organisation to mobilise their supporters and channel their energies into the mass resistance which is complementary to all guerrilla campaigns . . .’

And yet it was precisely those who would be regarded as ‘political’ from Farrell’s standpoint, who went on to betray the movement during the next decade. And it was just those who, with very good reasons, deeply distrusted ‘politics’ who eventually founded the Provisional IRA – an organisation that, in the latest phase of struggle has held British imperialism at bay for over 12 years on the basis of mass support of the nationalist population in the Six Counties. It is Farrell’s explanation that is inadequate. There is a great deal which Farrell, because of his own political standpoint, cannot begin to explain.

The revolutionary wing of the national movement has always made the unification of Ireland its central goal. It is the key to any social progress in the whole of Ireland. It is the pre-condition for uniting the Irish working class. And finally, it has been established, time and again, that it can only be achieved by revolutionary means – by an armed struggle to drive British imperialism out of Ireland. Those who counterpose ‘political’/‘economic and social’ agitation to the armed struggle to reunite Ireland have not understood the centrality of the national question for the Irish revolution and the Irish working class.

The Border Campaign showed two things. The first was that the social and political conditions still did not exist to unite a mass movement behind a military and political struggle to defeat British imperialism in Ireland. The second was that the Republican Movement made a major political error in its approach to the neo-colonial government in the 26 Counties. Let us examine them in turn.

The campaign aimed to bring the Six Counties to a standstill. It intended, as support built up, to liberate large areas ‘where the enemy’s writ no longer runs’. In attempting to do this, it faced almost insurmountable obstacles. The Six Counties was artificially created by British imperialism precisely to give the loyalists an inbuilt majority. Two-thirds of the population of the Six Counties are Protestant, the majority of whom are opposed to a united Ireland. The IRA would not only have to face the armed paramilitary forces of the loyalist state backed by the British army, but, in many areas, a hostile Protestant population as well. Under these circumstances only the active support of large sections of the nationalist population for the armed struggle and determined resistance to the loyalist state could guarantee a basis for a continuing military campaign.

In fact it was only in the border areas where the IRA could count on anything like widespread popular support. The decision not to engage in any actions in the Belfast area was an expression of this reality. This was a fundamental factor behind the failure of the campaign. Conditions do not permanently exist where there is active support for the armed struggle to drive British imperialism out of Ireland.

By the end of the 1960s, conditions were to rapidly change. The repression directed against the Civil Rights campaign had demonstrated in practice that the loyalist state was unreformable and would have to be destroyed. The revolutionary standpoint of the IRA was vindicated. The nationalist population of Derry and Belfast were to be left with no choice. They turned to the IRA demanding that it take up arms to defend the nationalist population against the paramilitary forces of the reactionary loyalist police state.

The belief that a declaration not to engage in actions in the 26 Counties would lead the Dublin government to tolerate the campaign was a major political error. Once Fianna Fáil had introduced internment and rounded up most of the political and military leadership of the Republican Movement, the campaign suffered a blow from which it could not recover.

Since 1914, the Irish capitalist class has always worked hand-in-glove with British imperialism to destroy the revolutionary national struggle to unite Ireland. It has no more interest in creating the conditions for a united Irish working class than has British imperialism. The political parties of the Irish capitalist class, Cumann na nGaedheal (Fine Gael) and Fianna Fáil, have, since the Civil War, taken every opportunity to crush the IRA. The capitalist neo-colonial state in the 26 Counties is a barrier on the way to a united independent Irish Republic. It, just like the loyalist state in the North, will have to be destroyed if British imperialism is to be defeated in Ireland.

By 1958, Fianna Fáil was about to embark on a policy of export-oriented growth through a massive influx of foreign capital, mainly British and US, into Ireland. Throughout the next two decades, Ireland’s economic dependence on imperialism would grow. At the time of the Border Campaign Fianna Fáil was already looking to better economic relations with Britain to stabilise the crisis-ridden Irish economy. It was in no position to tolerate a resurgence of the armed struggle of the IRA against British imperialism. The writing was on the wall. In spite of bitter experience in the past and many warnings to the contrary, the IRA ignored this. As a result, the organisation suffered a devastating blow.

Communists and the Border Campaign

The initial raids in December 1956 were responded to with the predictable denunciations in Dublin, London and Belfast. However, the Soviet Union, through Pravda denied British claims that the raids were only isolated actions without popular support. It argued in defence of the campaign that ‘Irish patriots cannot agree with Britain transforming the Six Counties into one of its main military bases in the Atlantic pact’.

The British Communist Party’s coverage of the campaign consisted on the whole of short factual reports without comment. However, a major article on the campaign by Desmond Greaves in January 1957 continued with the change of position that had come to the fore after the 1939-40 campaign. But this time without directly condemning the IRA. In an article called ‘You May Disagree with their Methods, but the IRA have Just Aims’, Greaves outlined a position which is transitional to the openly reactionary standpoint of the CPGB today.

Greaves attacks Press propaganda which denounced the IRA as ‘bandits, thugs and murderers’ and explains their methods and tactics on the basis of what he regarded as their class position:

‘In its barest terms, the tactics of the IRA are those of the progressive lower-middle class continued into the period when the working class should be leading the struggle for national independence, but (for historical reasons) is not.’

The aim of the IRA, a united independent Ireland is ‘progressive and should receive the support of every British worker’. However, the method of achieving this aim is in the hands of British workers to decide.

‘The British workers could, and should insist and use their power to ensure that all effort to keep Ireland divided and dependent ceases forthwith. If we, the working class, do not do our job, then others will conduct the struggle and, of course, they will use the methods which their class position gives rise to.’

He then goes on to make it clear that if there were no Partition there would be no IRA and after arguing that British workers need neither adopt nor accept responsibility for IRA tactics he says:

‘. . . it is the private business of the various political organisations in Ireland what tactics they choose in their struggle for their rights.’ (Daily Worker 3 January 1957)

Greaves’ position is deliberately evasive on the question of armed struggle and is, therefore, open to thoroughly reactionary conclusions. The armed struggle cannot be put down to the tactics of the ‘progressive lower-middle class’. The armed struggle is adopted by all classes, including the working class, as and when necessary to reach the desired goal. Has Greaves forgotten that Connolly was one of the leaders of the Easter Rising? Greaves, in fact, refuses to say whether British workers should be for or against the armed struggle that the IRA is actually conducting in the fight for a united independent Irish Republic. Communists cannot be evasive on this issue. They must take sides.

‘National self-determination is the same as the struggle for complete national liberation, for complete independence, against annexation, and socialists cannot – without ceasing to be socialists – reject such a struggle in whatever form, right down to an uprising or war.’ (Lenin 1916)

The communist standpoint is clear and it is Greaves who has broken with it.

The debate following Greaves’ article showed what was at stake. A letter from John Harris opposing Greaves drew out openly reactionary consequences.

‘For Desmond Greaves to describe the acts of terrorism perpetrated by the IRA as “tactics” is complete nonsense . . . who knows, the use of terror may even be extended to London, in which case Desmond Greaves would be hard put to explain them away.’ (Daily Worker 5 January 1957)

Indeed he would! And when the campaign was extended to London in the 1970s the CPGB, along with most of the British Left, condemned the IRA.

Letters in the Daily Worker of 9 January 1957 in reply to John Harris expressed the real communist standpoint. One argued that John Harris’ anger was misdirected:

‘Let John Harris direct his anger against himself and his fellow-members of the British Labour and trade union movement who have been too indifferent far too long to the injustice of the British-imposed partition of Ireland . . .’

Another pointed out that the struggle of the IRA aided the British workers’ struggle for socialism.

‘What Mr Harris does not realise is that any blow, whether by the IRA or anyone else, struck at British imperialism, helps the British people towards socialism.’

Revolutionary nationalism vs revisionism

After the end of the Border Campaign the IRA was in disarray. Disputes that had flared up among the leadership in the Curragh internment camp during the campaign created bitter divisions in the movement and led to many resignations. And there were bitter recriminations from some against those who had called off the campaign.

It is precisely in such periods of demoralisation and defeat that revisionist influences can take root in a revolutionary movement. And that is what happened. Unfortunately, these new influences were associated with ‘socialist’ and ‘communist’ politics. In fact, the ‘socialism’ of this new trend had little in common with the communist tradition. On the contrary, the views and positions of those involved, as later events were to conclusively confirm, put these so-called ‘socialists’ and ‘communists’ in the ‘evolutionary socialist’, revisionist camp of the Second International. The Communist International, in fact, was formed in opposition to this trend (see FRFI 8).

When the turmoil in the movement was over, Cathal Goulding became Chief-of-Staff of the IRA, a Dublin accountant Tomas Mac Giolla became President of Sinn Féin and a computer scientist, Dr Roy Johnston, considered to be a Marxist, became the movement’s education officer. All these three were to play a leading role in the creation of the Official IRA – later to become the pro-imperialist, pro-Stormont Sinn Féin the Workers Party.

Many on the Left have portrayed the dispute between the two trends in the Republican Movement as that between socialism and a narrow nationalism, between ‘political’ agitation on ‘social and economic issues’ and ‘physical force’ Republicanism. Nothing could be further from the truth. The split was over the way forward for the Republican Movement. It involved choosing between the revisionist and the revolutionary national position on the fundamental issues of the Irish revolution: can imperialism be reformed; the centrality of the national question; the question of armed struggle; the question of participation in the imperialist-imposed partitionist parliaments, Stormont and Leinster House, and the imperialist parliament itself at Westminster.

Sean Mac Stíofáin, the first Chief-of-Staff of the Provisional IRA made it clear when commenting on the new trend which developed in the Republican Movement after 1962, that revolutionary nationalists were not opposed to agitation on economic and social issues as such. Only that they saw the real danger of such agitation being separated from the national question.

‘By 1964, however, it was apparent that some of the new leadership were heading off in a very different direction. They were becoming obsessed with the idea of parliamentary politics and wished to confine the movement almost entirely to social and economic agitation. It went without saying that agitation on social and economic issues was part of the struggle for justice. But I believed that we should not allow ourselves to get so committed to it that we would lose sight of the main objective, to free Ireland from British rule. It was British domination which had led to many of the abuses, and injustices that called for social agitation.’

Mac Stíofáin’s doubts were confirmed in 1969 when the IRA found itself totally unprepared to defend the beleaguered nationalist population in Derry and Belfast against the B-Specials and RUC thugs.

Cathal Goulding further confirms Mac Stíofáin’s view in an interview he gave in 1970. After putting down the failure of the 1956-62 campaign to the people ‘having no real knowledge of our objectives’ he stated how they intended to overcome this:

‘Our first objective . . . was to involve ourselves in the everyday problems of people; to organise them to demand better houses, working conditions, better jobs, better pay, better education – to develop agitationary activities along these lines. By doing this, we felt that we could involve the people, not so much in supporting the Republican Movement for our political ends but in supporting agitation so that they themselves would be part of a revolutionary force demanding what the present system couldn’t produce.’ (our emphasis)

The roots of future revisionism lie in this statement. First we will take up the ‘everyday problems of the people’ and then . . . the national question. But this is a break from the revolutionary nationalist position. For it separates the social and economic issues facing the people from their source – British domination over Ireland. The centrality of the national question for the Irish people is, in fact, put to one side, to be taken up at a later stage.

The revisionist trends within the movement soon became embodied into a political programme. It contained nine proposals the most important of which was to abolish the traditional policy of parliamentary abstentionism – one of the most important foundations of the Republican Movement. It proposed that Republican candidates if elected would take their seats in the Dublin, Stormont and Westminster parliaments. It was this issue which directly precipitated the split. But at the heart of the division was the defence by the Provisional IRA of the revolutionary nationalist position.

The Provisional IRA knew that imperialism could never play a progressive role. They understood that the Stormont parliament in the North, and the Leinster House parliament in the South, creations of imperialism, had to be destroyed if a united Irish Republic was to be achieved. Finally, they recognised and proclaimed the necessity of revolutionary armed struggle if British imperialism was to be driven out of Ireland.

A great deal has been made of the ‘anti-communism’ of the Provisionals in the first few years of their existence. This attitude derived from their actual experience of so-called communist organisations in Britain and Ireland. These organisations had long since broken with the communist tradition. The Communist Party of Ireland after the war took what can only be regarded as a pro-Unionist position, participating in elections in the North, and opportunistically abandoning an anti-partitionist position. The CPI went so far as to organise itself on partitionist lines creating separate parties for the Six Counties and 26 Counties. Many individual so-called ‘communists’, and associated groups, the Connolly Association, the CP of Northern Ireland, the Irish Workers’ Party, were all involved in supporting or building up the revisionist trend in the Republican Movement. Also the British Communist Party had long since given up a principled position on the question of Ireland. Mac Stíofáin quite clearly explained his position:

‘Certainly as revolutionaries we were automatically anti-capitalist. But we refused to have anything to do with any communist organisation in Ireland, on the basis of their ineffectiveness, their reactionary foot-dragging on the national question, and their opposition to armed struggle.’

The final word on the two trends in the Republican Movement can safely be left to an article printed in the Provisional’s newspaper An Phoblacht of June 1971:

‘Other contenders for the title of Republicanism (and there are many) will term the revolutionary as the one with the most in political jargon of the Left – the pious exhortation to the people to rise to a socialist Utopia before ever attaining National Unity – freedom and independence – or the misguided idea that sitting in Leinster House is “a new weapon in the hands of the revolutionary”. You don’t destroy something by joining it and giving it credibility and credence. You don’t break up an oil slick by swimming through it – you burn it. The real revolutionary is the man who sees the issues clearly, preaches the alternatives and risks his neck (not his necessary popularity and Dáil seat) in the destruction of imperialism.’

David Reed

August 1981

Continued in Part Seven

[Material from this article later went on to become part of Ireland: the key to the British revolution by David Reed]