Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! no. 13, October/November 1981

What began, in the late 1960s, as a struggle of the minority nationalist population for basic democratic rights in the six north-eastern counties of Ireland, was soon to be turned into a revolutionary war to drive Britain out of Ireland. In that period, it was to be conclusively demonstrated in practice that the northern statelet was unreformable. Basic democratic rights for the nationalist population could only be achieved by ending Partition and driving British imperialism out of Ireland. They could only be achieved by revolutionary means.

Unionism gets a face-lift

The Six Counties statelet could not have been brought into existence without the political support of the Protestant working class. Nor could it be maintained without that support. However, that support can only be sustained on the basis of sectarianism. That is, by maintaining the privileged status and conditions of the Protestant working class. For such privileges are the foundation of their loyalty to the Union with Britain and therefore the key to imperialist control over the whole of Ireland.

British imperialism cannot play a progressive role in Ireland. For it has no interest in eliminating sectarianism or reuniting the Irish nation and the Irish working class. This is the context in which we will examine the years immediately before the Civil Rights Movement. This is the background which is necessary to understand the role played by the so-called ‘liberal’ Unionist Terence O’Neill.

The economy of the Six Counties statelet was in very serious difficulties in the late 1950s. Its three traditional industries – agriculture, textiles (linen industry) and shipbuilding – were in long-term decline. Employment was rapidly dropping in all three. In agriculture, between 1950 and 1961, employment fell by nearly 40%. Between 1955 and 1965 employment in the linen industry fell by 37%, and in shipbuilding it fell by 42%. In 1961, 10,000 men were made redundant in the Belfast shipyards. Unemployment was now reaching unacceptable levels among the Protestant skilled working class. Average earnings also fell from 82% of those in Britain in 1961 to 76% in 1966. If these developments were allowed to continue unabated, the loyalty of the Protestant working class, and with it the Unionist class alliance, would come under severe strain.

The political impact of these changes soon began to show. Sections of loyalist workers began to seek an alternative to the Unionist Party to defend their interests and guarantee their privileges. The Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP), which had split in 1949 over its recognition of the border, could now put itself forward as an alternative to the Unionist Party which could attract loyalist workers. In 1953, the NILP obtained 31,063 votes (12.1% of the total) in the Stormont elections with nine candidates winning no seats. By 1958, it had won 37,748 votes (16%) with eight candidates, winning four seats. In 1962, it obtained 76,842 votes (26%) with 14 candidates – its highest total ever – and held on to the four seats won in 1958 with substantially increased majorities. No new seats were gained but the Unionists’ majority in some seats was sharply reduced. This was a protest vote which the Unionists could not ignore. If the Unionist class alliance was to survive, the Unionist Party had to ensure it found jobs for loyalist workers.

The traditional response of Unionism was discrimination pure and simple. Even in 1961, Robert Babington, a Unionist barrister (later a MP) could still say:

‘Registers of unemployed Loyalists should be kept by the Unionist Party and employers invited to pick employees from them. The Unionist Party should make it quite clear that the Loyalists have first choice of jobs.’

Privileged access to jobs, however, presupposed that jobs were available. Having the ‘first choice of jobs’, which increasingly did not exist, would find little response from loyalist workers. A new approach was clearly required. Opposition to Brookeborough built up and in March 1963 he resigned. He was replaced by Terence O’Neill.

O’Neill has been widely portrayed as a ‘reformist liberal’ who attempted to reduce sectarianism and discrimination but was defeated by the old guard of Unionism. This is a distortion of the truth. O’Neill’s entire purpose was not to undermine Unionism but to revitalise it. As he said in April 1965:

‘Let no one in Ireland, North or South, no one in Great Britain, no one anywhere make the mistake of thinking that, because there is talk of a new Ulster, the Ulster of Carson and Craig is dead. We are building, certainly; but we build upon their foundations. And from that rock, no threat, no temptation, no stratagem will ever shake us. We stand four-square upon it.

‘But it is not enough, I would suggest to you, just to be part of the United Kingdom. We want to be a progressive part of that Kingdom. We want to secure for our people the full fruits of this great nation’s prosperity. It must be our aim to demonstrate at all times, and beyond any possible doubt, that loyalty to Britain carries its reward in the form of a fuller, rich life.’

O’Neill’s intention was to strengthen the Six Counties statelet. The equation of loyalty with material privileges, and with the importance of the British link for securing these privileges, was central to his approach. The task was to secure the Unionist class alliance. This could only be done by restoring the eroded privileges of the loyalist working class.

If the loyalist workers were to maintain their privileges and stay ‘loyal’, industry in the North had to continue to provide jobs. British subsidies to existing industries could now only slow down the pace of decline, they could not halt it altogether. To ensure new jobs were provided, O’Neill embarked on a far-reaching programme to attract capital investment from outside the Six Counties statelet.

Attracted by capital grant rates of up to 45%, together with various other direct and indirect subsidies, the 1960s saw a massive rise of firms investing in the Six Counties. While 51 firms were established with government assistance between 1950 and 1959, in the period 1960-1969 no less than 172 firms were set up. This rapid growth took off in 1963, the year Terence O’Neill took over.

The impact on employment was crucial. In 1961 the number of jobs created by government sponsored industry was 40,300 – 20.5% of all manufacturing jobs; it was 64,200 (34.4%) in 1966 and 78,680 (43.2%) in 1971. The government strategy was also successful in attracting a number of large multinational corporations such as Michelin, Goodyear, Du Pont, Enkalon, ICI and Courtaulds, to invest in the Six Counties. The northern statelet became a major centre of the artificial fibre industry.

The influx of imperialist capital into the Six Counties led to a shift in the economic balance of power. The old established family firms which had been the backbone of the Unionist Party were in decline. They were being displaced by the more modern highly productive firms established by imperialist capital. However, it is totally misleading to maintain that this development represented a liberal and reforming influence which could have undermined the sectarian foundations of the Six Counties statelet. On the contrary, it was only on the basis of the influx of new British and foreign capital that the Unionist class alliance could be secured and with it the foundation of the Six Counties statelet.

Evidence of the ‘reforming’ influence of these new developments was said to be the fact that, in August 1964, the Unionist government under O’Neill recognised an autonomous Northern Ireland Committee of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions. Brookeborough had always refused to recognise the ICTU. He was violently opposed to trade unions and especially opposed to an all-Ireland body. However, the Unionist government under O’Neill understood the necessity for union cooperation and ‘normal’ labour relations, if the new investment they urgently needed was to be attracted to the Six Counties. Anyway, recognising an autonomous Northern Ireland Committee of the ICTU was far from undermining the sectarian character of the Six Counties statelet. Rather, it acknowledged it by accepting a partitionist division of the Irish trade union movement and creating what was, in fact, a loyalist dominated trade union committee.

Other evidence put forward as an example of the ‘liberal’ influence of O’Neill’s new strategy was the meeting he had on 14 January 1965 in Belfast with Seán Lemass, Taoiseach of the 26 Counties Fianna Fáil government. There was also a return visit in Dublin in February 1965 and inter-departmental and inter-ministerial discussions followed.

In the 1960s, Fianna Fáil had embarked on a new economic strategy of export-oriented growth through massive influx of foreign capital. In 1960, Lemass had signed a trade agreement with Britain after a series of talks which had begun in July 1959. At that time, Lemass had also suggested economic cooperation between the 26 Counties and the Six Counties, but Brookeborough had shown no interest. The new strategy was successful for a time in increasing employment and economic growth. By March 1965, 234 new foreign enterprises had been established in the 26 Counties, 40% of them British. Trade ties with Britain became closer and an Anglo-Irish free trade area was agreed on in December 1965. This is the background which had led some to believe that the Lemass-O’Neill talks heralded a new era of North-South cooperation and possible steps towards the reunification of Ireland under British imperialist rule.

O’Neill very quickly put down such talk and made it clear that discussions were only concerned with limited economic cooperation with the 26 Counties. It was part of his overall strategy to revive industry in the Six Counties and make foreign investment more attractive. There was no question of discussing political or constitutional changes at all. As he said some time later to an Annual Meeting of the Ulster Unionist Council in Belfast (February 1967):

‘Because I talk to my neighbour in a friendly way across the garden fence, and perhaps even agree that we should share some gardening tools with him, it does not mean that I intend to let him live in my house.’

The overall results of O’Neill’s economic programme demonstrated that, far from undermining the sectarian foundation of the loyalist state, it reinforced it. The bulk of the new investment was located in the predominantly Protestant East of the Six Counties. So that unemployment, while falling dramatically in loyalist areas, remained constant or even increased in nationalist areas during the period. In June 1970, the average unemployment level (11.3%) in the predominantly nationalist area West of the River Bann was nearly twice the Six Counties average (6.2%). In some nationalist areas of Belfast and Derry it was well over 20%.

Even where investment was located outside loyalist areas, as the following case shows, discrimination along sectarian lines was very much in evidence. It was reported in 1977 that two-thirds of the workforce at the Ford Motor Company’s Autolite factory in West Belfast was Protestant. The factory was situated in the nationalist area of Andersonstown where there is massive unemployment. Protestants held the best jobs within the factory and many travelled to work from as far as Bangor and Portadown, ten or twenty miles away. A few years earlier it had been discovered that the then personnel officer was simply tearing up applications from Catholics. He was not dismissed but simply moved to another position with the same status and salary. In 1977, the personnel officer vetting applications was a sergeant in the notoriously sectarian Ulster Defence Regiment.

Following the Matthew Report (1963), the government established a new city planned to have a population of 100,000, as an alternative to Belfast, and proposed seven other towns as industrial growth centres. The new city included the Protestant towns of Lurgan and Portadown and the area between them. It was provocatively named Craigavon after the founder of the loyalist statelet. Six of the eight ‘growth centres’ were within 30 miles of Belfast in loyalist territory. Under the Benson Report on Northern Ireland Railways (1963) the rail links from Belfast to Newry, and the line to Derry through Omagh and Strabane were axed – all predominantly nationalist areas. The Lockwood Report (1965) recommended that the New University of Ulster was not sited in nationalist Derry, the second largest city in the Six Counties, where there was already an old-established University college, but in Protestant Coleraine. Under O’Neill; the economic and social revival of the Six Counties was based on sectarianism and therefore largely benefited the Loyalists.

The Unionist Party got its reward. There was a loss of support for the NILP and a return of Protestant working-class votes to the Unionist Party. The NILP vote fell from 76,842 (26%) in 1962 to 66,323 (20.4%) in 1965, when it lost two of the four seats it had won in 1958, to 45,113 (8.1%) in 1969. The Unionist class alliance had been well and truly secured.

The Civil Rights Movement

In the course of reinforcing the Unionist class alliance, O’Neill succeeded in reactivating the latent opposition to the loyalist statelet amongst the nationalist minority. The sectarian economic and social measures implemented by the O’Neill administration could only serve to highlight the discrimination against the nationalist population.

Within the Catholic middle class a movement for civil rights emerged. In a few years this movement, under a new and more radical leadership was to turn into a mass movement intent on destroying the loyalist state.

A much larger, more ambitious Catholic middle class had been created in the Six Counties as a result of the post-war developments generally associated with the growth of the ‘welfare state’. Developments in the education system, including the increase in University scholarships, were of particular significance. By the mid-1960s, a section of middle-class Catholics, who did not see their interests being advanced through unity with the 26 Counties, were willing to work within the institutions of the loyalist statelet to end discrimination and improve their status.

In January 1964, a group of middle-class and professional Catholics founded the Campaign for Social Justice which set about collecting and publicising information about gerrymandering and discrimination in the Six Counties. As a result of this and other agitation by middle-class Catholics together with pressure from anti-Unionist MPs in the Six Counties parliament, in June 1965, a group of back bench Labour MPs in the Westminster parliament set up the Campaign for Democracy in Ulster. Included among them was Stanley Orme, the left-wing Labour Party MP who was later to administer internment when he became Minister of State for Northern Ireland in 1974. Pressure was put on the Stormont government to introduce reforms but none were forthcoming.

Opposition to the O’Neill administration also existed within the loyalist camp and included sections of the Unionist Party. Those opponents took every opportunity to challenge O’Neill for what they regarded as his break from the traditional loyalist attitude to the nationalist minority. One of his more vociferous opponents was Ian Paisley. Paisley had set up his own violently anti-Catholic Free Presbyterian Church in 1951. As unemployment grew in the later 1950s, he built an organisation called the Ulster Protestant Action whose aim was ‘to keep protestant and loyal workers in employment in times of depression, in preference to their catholic fellow workers’. His movement was built on the streets and its sectarian actions often led to violent rioting.

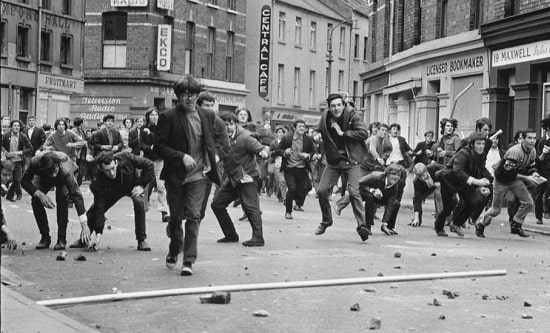

During the 1964 Westminster elections, the Republicans were contesting a seat in West Belfast and had placed a tricolour in the windows of their election headquarters in Divis Street on the Falls Road. The RUC had given up interfering with tricolours in nationalist areas. On 27 September, Paisley, at a meeting in the Ulster Hall, threatened to lead a march to take it down himself if it was still there in two days’ time. The day after Paisley’s threat, the government, needing every loyalist vote it could drum up to win the seat, sent in 50 RUC men to remove the flag. They broke down the door of the Republican headquarters and took it down. A few days later it went up again. The RUC used pick-axes to break into the office and again took it down. That night Belfast had its worst sectarian riots since 1935. The RUC had water cannon and armoured cars. The nationalist defenders replied with petrol bombs. Next evening 350 RUC men wearing military helmets and backed by armoured cars were sent into the Falls Road to smash the resistance there. Over 50 civilians were taken to hospital. In Dublin, 1,000 demonstrators marched on the British embassy in protest and stoned the Gardaí on duty there.

Needless to say, the Unionist Party candidate, James Kilfedder, won the election. He thanked Paisley ‘without whose help it could not have been done’. O’Neill himself went so far as to accuse Republican candidates of ‘using a British election to try to provoke disorder in Northern Ireland’.

Paisley’s challenge built up. In 1965 he accused O’Neill, after the Lemass-O’Neill talks, of entertaining at Stormont a ‘Fenian Papist murderer’. He staged a massive rally outside the Unionist Party headquarters and forced O’Neill to abandon a function due to take place. In February 1966 he launched a paper, the Protestant Telegraph, which contained hysterically anti-Catholic and anti-communist propaganda, and in April he set up the Ulster Constitution Defence Committee (UCDC) to coordinate his movement, with the Ulster Protestant Volunteers (UPV) as its vanguard.

In April 1966, Paisley’s agitation led the government to mobilise the B-Specials for a month and to ban trains from the 26 Counties coming to the commemorations of the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising. On 6 June, Paisley led a demonstration through Cromac Square – a nationalist area of Belfast. Local residents tried to block the road and were attacked by the RUC. After a short battle, Paisley went on to where the Presbyterian General Assembly was meeting – where his followers tried to break through a police cordon to attack the meeting place. After pressure from the Wilson government on O’Neill, Paisley was eventually arrested and prosecuted. He went to jail for three months after refusing to be bound over for two years. His followers reacted violently and there were riots outside the prison.

In February, March and April 1966, a number of petrol bomb attacks on Catholic shops, homes and schools had taken place and one woman had been killed. On 27 May, a Catholic man, John Scullion, was shot and fatally wounded in Clonard Street off the Falls Road. On 26 June three Catholic barmen were shot as they left a pub in Malvern Street. One was killed. Three men (including ‘Gusty’ Spence) were arrested and charged with the murder. They were later found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment. They belonged to the Ulster Volunteer Force – a small group of Paisley supporters who had set up an armed organisation. The UVF was also responsible for the petrol bombings and the murder of John Scullion. Those responsible for the murders belonged to the Prince Albert Loyal Orange Lodge. On 12 July 1967, during its annual parade, the Lodge on passing the gates of Crumlin Road jail in Belfast stopped to pay homage to the three murderers held inside.

The government banned the UVF under the Special Powers Act and O’Neill let it be known that a leading member of the UVF was a prominent official of Paisley’s UCDC. He was Noel Doherty, secretary of the UCDC, a printer who had set up the presses of the Protestant Telegraph, a B-Special and a Unionist candidate in the Belfast Corporation elections in 1964. It says a great deal about the nature of the sectarian statelet that Paisley’s brand of loyalism now commands massive support.

O’Neill’s own assessment of the UVF murders is instructive. His main concern was that the growing tide of nationalist protest might gain a hearing in Britain. It was vital if Ulster was to remain a loyalist state that an acceptable face be presented to the world whatever the reality within. In a speech to the Mid-Armagh Unionist Association in November 1966 he argued:

‘The events of 1966 have turned an intense and curious scrutiny upon us. And as we stand in this spot-light it remains as true now as it was over half a century ago that we must have the understanding and support of a substantial proportion of the British people. That is why we must condemn recent extremist activities which would not be supported by any of the British political parties or even by a single British MP. Of course, we cannot please everyone. There are certainly strong Southern Irish forces in Great Britain, with spokesmen in Parliament, who seek nothing less than the reunification of Ireland. We cannot please that section of opinion and we are not going to try.

‘. . . If we can demonstrate that behind all the talk about “discrimination” is a warm and genuine community spirit; if we can demonstrate that we seek the advantages of British citizenship only because we bear the same burdens – then the voices of criticism will fall increasingly upon deaf ears . . .

‘I do not want Ulster to change its nature, but rather to show again its best face to the world . . .’. (our emphasis)

O’Neill was a staunch Unionist and an Orangeman who marched with his Orange Lodge every 12 July. After he became Prime Minister, he joined two other off-shoots of the Orange Order, the Apprentice Boys and the Royal Black Preceptory. While attempting to present Ulster’s ‘best face’ to the world, he had taken no steps to end: gerrymandering of local government, sectarian discrimination against Catholics, and the existence of the Special Powers Act and the B-Specials. It was against this background that in January 1967 the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) was formed.

After the defeat of the 1956-62 campaign, the IRA, under the direction of the new revisionist leadership (see FRFI 12) had turned to ‘economic and social agitation’ within the system as the means to bring it down. They set up Republican Clubs as part of a strategy of engaging in open and legal political action. In 1967, William Craig, Minister of Home Affairs, banned the Republican Clubs saying they were front organisations for Sinn Féin and illicit recruiters for the IRA. This happened just before celebrations, planned for the 100th anniversary of the Fenian uprising, were to take place. The Republicans retaliated by having a ‘banned’ public meeting which was attended by civil liberties representatives, Gerry Fitt, elected in March 1966 as Republican Labour MP for West Belfast, and other interested observers. A few prominent Republicans were arrested but later released. Left-wing students and Young Socialists also held protest marches in Belfast against the banning.

The Republican Movement had also set up Wolfe Tone Societies as discussion forums for Republicans, communists, socialists and other left-wing radicals. It was through such societies in the Six Counties and the Republican Clubs that the IRA was to play a significant role in the Civil Rights Movement. NICRA’s official foundation took place at a public meeting in January 1967. However, it could be said to have been formed earlier in August 1966 at a secret meeting, in Maghera Co Derry, at which Cathal Goulding, the IRA Chief of Staff supported the plans for the movement. And as a result, the IRA played a significant part in the open Civil Rights Campaign.

NICRA was modelled on the National Council for Civil Liberties in Britain. A broad-based committee was founded to run the movement and included Republicans, members of the Communist Party, trade unionists and individuals from committees associated with earlier campaigns for reforms. For the first year of its existence, it carried out activities similar to its predecessor, the Campaign for Social Justice. NICRA eventually adopted a series of demands, none of them in themselves revolutionary, as the basis of the movement. They were:

- One-man-one-vote in local elections

- The removal of gerrymandered boundaries

- Laws against discrimination by local government, and the provision of machinery to deal with complaints

- Allocation of public housing on a points system

- Repeal of the Special Powers Act

- Disbanding of the B-Specials

The fight for these demands, however, would very soon lead the Civil Rights Movement into direct conflict with the loyalist state.

In Caledon, Co Tyrone, the local Republican Club was giving support to homeless Catholic families squatting in newly-built council houses. The Unionist-controlled Dungannon Rural Council wouldn’t allocate houses to them. In June 1968, a Catholic family was evicted from a council house in which they had been squatting. A nineteen-year-old unmarried Protestant, Emily Beattie, secretary to a local Unionist politician, was allocated the house. Austin Currie, a Nationalist MP in Stormont, who had been raising the matter, occupied the house in protest and was evicted and fined.

In August 1968, the Dungannon-based Campaign for Social Justice decided to hold a march from Coalisland to the Market Square, Dungannon, to protest against the sectarian housing policy. With some reluctance NICRA agreed to support the march and it was announced for 24 August. Paisley’s UPV immediately called a counter-demonstration and promised violence if the march entered the Market Square, Dungannon. The RUC then rerouted the march from the centre of the town.

The march was a remarkable success. By the time it reached the barrier the RUC had erected, between 3,000 and 4,000 were present. The IRA leadership encouraged its members to support the march. The RUC in fact estimated that 70 of the stewards on the march were Republicans and 10 of them were members of the IRA.

About 1,500 UPV counter-demonstrators, many of them members of the B-Specials, were gathered in the Market Square. When the Civil Rights march reached the RUC barrier a few scuffles took place and the organisers stopped the march and held a rally. After speeches, the leaders of the march advised the marchers to go home. Instead, the marchers sat down in the road singing songs and staying there until quite late into the night.

As Seán Mac Stíofáin so accurately commented seven years later, ‘little did the handful of people who sponsored it, or the Republican leadership who supported it, imagine where that first civil rights march was to lead the entire nation’. It took one more demonstration in Derry on 5 October 1968 to turn the Civil Rights Campaign into a mass movement.

Derry was an obvious place to have the next Civil Rights march. It had a nationalist majority yet it was Unionist controlled. There was massive unemployment – one in five out of work. Vast inequalities in housing – a nationalist city where in the 1960s, a council house was the gift of the Protestant mayor.

The request for the march came to NICRA from local activists, Republicans and socialists. It was planned for 5 October 1968. The proposed route was to be along business streets from the Waterside station on the East side of the Foyle, across Craigavon Bridge and to the Diamond in the centre of the city. Since the RUC had batoned the anti-Partition League off the streets in the 1950s, no anti-Unionist demonstration had attempted to go through the walled city.

Five days before the march was due to take place, the Apprentice Boys of Derry gave notice of an ‘annual’ parade passing exactly over the same route as the Civil Rights march on the same day. No one had ever heard of the ‘annual’ parade before, but it had the desired effect. William Craig, Minister of Home Affairs, banned the march. NICRA wanted to call the march off, but after being told by Derry activists that they would march anyway, it went ahead.

On 5 October, about 2,000 (Eamonn McCann, one of the organisers of the march says 400 with 200 looking on) marchers set off from Waterside station and got about 200 yards before they were met by a solid wall of the RUC. As the march reached the police cordon, the RUC waded in. The first to be batoned was Gerry Fitt MP who was one of those leading the march. The marchers soon found out that they were caught between two lines of police in a narrow street. The police savagely batoned the marchers and hosed them at close range using water cannon. Men, women and children were clubbed to the ground. Nearly a hundred people were treated in hospital.

Later, there was fighting at the edges of the Bogside – a staunch nationalist area of Derry – which lasted until the early morning. Police cars were stoned, shop windows smashed, petrol bombs thrown, and barricades were erected.

The march had been covered by television and millions in Ireland and Britain had seen the armed thugs of the RUC smashing up a peaceful demonstration. Millions were horrified when they saw the naked facts of loyalist state violence. The nationalist minority in the Six Counties was experiencing the limitations of non-violent action in opposition to the sectarian policies of the loyalist state. A peaceful demonstration had been batoned off the streets. The 5 October 1968 proved to be another turning point in Irish history.

The real face of Unionism

Events now began to move very quickly indeed. A number of demonstrations by students took place in Belfast. People’s Democracy, a loose activist body of left students committed to civil rights reforms was set up and involved in various actions including a sit-in in Stormont. On 15 October, the Nationalist Party withdrew as the official ‘opposition’ in Stormont. On 4 November, Harold Wilson, recognising the need to contain the Civil Rights Movement, saw O’Neill, Craig and Faulkner and demanded they introduce reforms urgently.

Another march was planned in Derry for 16 November over the original route of the earlier march. On 13 November, Craig banned all marches inside the walled city for a month. Three days later, 15,000 Civil Rights marchers assembled and attempted to march into the city centre. The march was confronted by a massive force of RUC. The organisers – the moderate broad-based Derry Citizens Action Committee led by John Hume and Ivan Cooper – prevented a violent confrontation as marchers and RUC stood face-to-face for 30 minutes. Eventually, the police barricades were breached, the RUC recognising that they were powerless to stop the marchers. Eventually thousands reached the city centre – the Diamond – and a meeting was held. It was a remarkable victory. The Unionists had got together more RUC men than ever before and they had been beaten. If the swelling tide of the Civil Rights Movement was to be contained, the government would have to grant reforms.

On 22 November, O’Neill announced a package of planned reforms. Derry Corporation would be abolished and replaced by a Development Commission. A grievance investigation machinery would be considered and an Ombudsman appointed. Local authorities would be encouraged to allot their houses on the basis of a ‘points’ system. The company vote would be abolished for local elections, and the government would consider suspending part of the Special Powers Act as soon as conditions allowed it to be done ‘without undue hazard’. But the nationalist minority had gone beyond accepting such cosmetic change. Another demonstration was announced for Armagh on 30 November.

By this time, O’Neill was being seriously challenged by hard-line Unionists in his party. They recognised all too clearly that granting the demands of the Civil Rights Movement and ending discrimination would destroy the privileged position of loyalist workers and the loyalist petit-bourgeoisie in the Six Counties state. Unless the Civil Rights Movement was halted then it would threaten the very existence of the sectarian statelet itself. The Unionist ‘right’ now turned to more direct action against the Civil Rights agitation.

On the 30 November, having failed to get the Armagh march banned, Paisley and his right-hand man, a retired Army Major, Ronald Bunting, descended on the route of the march at 1am in the morning with 20 to 30 car loads of supporters. They set up barricades and armed themselves with sticks and other weapons, including pipes, sharpened at the ends. The RUC in fact seized two revolvers and 220 home-made weapons from them. About 5,000 Civil Rights marchers arrived in the town but they were blocked at a barrier put up by the RUC. 75 yards further down behind another barrier were assembled 1,000 Paisleyites armed with sticks and clubs. 350 RUC men had made no effort to remove them and had in fact given way to an armed loyalist mob. The Paisleyites had scored a victory over the Civil Rights Movement.

O’Neill went on television and appealed for support for his policies and his intended limited reforms. He called on the Civil Rights Movement to take the heat out of the situation as their voice, he said, had been clearly heard. Following his broadcast, NICRA called a ‘truce’ – marches were called off for a period of a month. On 11 December, William Craig was sacked from the government by O’Neill for making a speech criticising O’Neill’s policy.

At this stage, People’s Democracy announced a three-day ‘long-march’ of 75 miles from Belfast to Derry. They recognised that O’Neill’s limited reforms amounted to very little. They wanted one man one vote in local government elections and action on unemployment and housing. The march was opposed by NICRA.

The march began on 1 January 1969 with 80 participants. Every few miles loyalist thugs blocked the route. The RUC regularly diverted the march which was frequently stoned and attacked. At the nationalist village of Brackaghreilly near Maghera, the marchers were persuaded to stay in the Gaelic Hall. Shortly after, 50 armed men – the local company of the IRA – set up roadblocks. They had heard that the march was going to be attacked and had persuaded the marchers to stay in the village. Their information, however, had not been accurate. The major ambush was planned farther up the route at Burntollet, a few miles from Derry.

On 4 January at 8.30am about 200 loyalist thugs armed with iron bars and nail studded coshes, surrounded by heaped piles of stones, waited on a hillside for the marchers to arrive. 100 of these men were later identified as members of the Ulster B-Specials. The RUC had watched the gathering of the ambush, chatting with the B-Specials and made no attempt to stop it taking place. The march arrived led by an escort of 80 police. It was brutally attacked and marchers were beaten unconscious – one nearly drowning in a river as a result.

The battered marchers determinedly went on and eventually reached Derry. Most of the marchers were injured with many covered in blood. They were met in the Guildhall Square by thousands of angry Civil Rights supporters who were in no mood for a truce. Very soon battles broke out with the police who tried to drive those assembled back into the Bogside.

At 2am next morning a drunken mob of RUC men ran amok in the Bogside breaking down doors, smashing windows and beating up anyone in sight. Next morning the people in the Bogside organised; barricades were built, vigilante patrols carrying clubs patrolled the streets. A radio transmitter was installed in one of the flats. Free Derry was born. The RUC were kept out of the area for nearly a week. The barricades were only finally taken down after the Derry Citizens Action Committee – Hume, Cooper and others – had persuaded the people that they were no longer necessary. However, this was a foretaste of the momentous events yet to come.

Although O’Neill viciously attacked the marchers calling them hooligans he was forced by the pressure of the Civil Rights Campaign to announce on 15 January a government inquiry to investigate the disturbances and underlying causes – the Cameron Commission. It was this decision that accelerated the inevitable process, which was to bring O’Neill down. On 23 January, Faulkner resigned from the government in protest. On 3 February, 12 Unionist backbenchers called for O’Neill’s resignation. That evening O’Neill called an election for 24 February to try and get a mandate for his policies.

Paisley had been sentenced to three months imprisonment for the Armagh affair. He appealed and got out of jail to stand against O’Neill in the election – the first time O’Neill had not been elected unopposed since 1946. The result was inconclusive, with O’Neill back in power but having 11 anti-O’Neillite Unionists in the Parliamentary Party. O’Neill himself barely scraped home against Paisley obtaining 7,745 votes to Paisley’s 5,331, with a Civil Rights candidate holding the balance of 2,310. In Derry, McAteer, the leader of the Nationalist Party, lost to John Hume, the independent Civil Rights candidate.

The two sides were polarising. On 14 March, four of the ‘Old Guard’ members of NICRA – including Betty Sinclair of the so-called Communist Party – resigned in protest against the increased militancy of the Civil Rights Campaign. On 17 April a by-election for the Mid-Ulster seat at Westminster saw the election of Bernadette Devlin, a student member of People’s Democracy, who had won the nomination as a united anti-Unionist candidate. It showed that the entire nationalist minority had swung behind the increasingly militant Civil Rights Campaign.

Two days later there was a minor battle with the RUC in Derry with the youth of the Bogside using stones and petrol bombs to hold the police off. The police burst into a house in William Street and beat everyone up. Sammy Devenny, the owner of the house, later was to die from the injuries he received. The growing anger of the Bogside eventually forced the police to withdraw. There were fierce clashes between Nationalists and Orange marchers in Belfast and Dungannon with the RUC intervening on the loyalist side.

On 20-21 April, bombs went off wrecking an electricity link-up in Portadown and a blast went off at the Silent Valley reservoir in Co Down which provides water for Belfast. It was immediately assumed to be the IRA.

On 22 April, O’Neill finally accepted the only position which might placate the nationalist minority – one man one vote, universal adult suffrage. The next day, Chichester-Clark resigned. On the following day, the Unionist Parliamentary Party accepted the change by 28 votes to 22. Faulkner voted against.

That night, just after midnight, more explosions occurred wrecking water pipelines and leaving Belfast short of water. Three days later, Terence O’Neill resigned to be replaced on 1 May 1969 by Chichester-Clark. Months later it was revealed that the series of bomb blasts in March and April were the work of the loyalist UVF attempting to simulate IRA attacks with the object of forcing the waverers in the Unionist Party to bring O’Neill down. The battle lines were firmly drawn.

Insurrection – the Battle of the Bogside

On 21 May, desperate to hold back the growing militancy of the nationalist minority, and after a meeting between Harold Wilson and Chichester-Clark, Wilson announced that local elections would be held under ‘One Man, One Vote’. But this was much too late even though NICRA called a temporary halt to demonstrations.

In North Belfast, fierce battles took place in the Ardoyne over several weekends between the RUC and the nationalist working class. On 12 July, an Orange parade was stoned in Derry and for three days battles raged between the RUC and Bogsiders, with the RUC shooting and wounding two civilians. On 2 August an Orange march passed the nationalist Unity Flats in Belfast. The residents turned out to protest. The battles went on for three days with loyalist mobs, led by the recently formed Shankill Defence Association trying to attack the Unity Flats and Ardoyne. At one stage, serious clashes took place between the loyalist mobs and the RUC, with many being injured and arrested. The RUC eventually attacked the besieged residents of Unity Flats and an elderly Catholic, Patrick Corry, died in an RUC barracks after being beaten up by the police.

At the beginning of August, a detachment of British troops was moved into the RUC headquarters for stand-by use in Belfast. This time they were not used. But the direct involvement of British imperialism was increasing. 500 extra troops had already been flown into the Six Counties in August after the first UVF explosions to be used as guards over vital installations. On 16 July, Harold Wilson had already given Roy Hattersley, the Minister of State for Defence, the job of preparing for the intervention of British troops in the Six Counties.

The crunch was to come on 12 August, the day of the Apprentice Boys’ parade in Derry, when thousands of Orangemen come to Derry and parade through the city and around the walls to commemorate the lifting of the siege of Derry in 1689. It is an annual celebration of Protestant ascendancy and served to remind the nationalist population who was master even in the city of Derry with a nationalist majority.

The Stormont government turned down all appeals to have the march banned. The Bogside was cordoned off by the RUC. As the parade was passing one of the entrances of the Bogside, it was stoned. The RUC, closely followed by a loyalist mob, baton-charged and the battle was on.

At the end of July, the Republican Clubs had announced they had formed a Derry Citizens Defence Association and they invited other organisations to join. Most did. It was chaired by Sean Keenan, a veteran Republican. After the events in Belfast on 2 August it made plans for a defence of the area.

Barricades had gone up on 11 August in anticipation of the events to come. Once the battle was on, they were built all around the area. Open-air petrol bomb factories were established, dumpers hijacked from a building site were used to carry stones to the front line. First aid stations manned by doctors and nurses were set up. The radio transmitter used during the last major battle in January pumped out Republican music and messages to the fighters. Two-way radios taken off television crews were used for communications. The area was intensively patrolled.

The youth went on to the roof of a block of high-rise flats which dominated Rossville Street – the main entrance to the Bogside. They were continually supplied with thousands of petrol bombs – the dairy was said to have lost 43,000 bottles. This was the decisive move. As long as they were there the police could not get past the flats. Every time they tried, petrol bombs rained on them.

The RUC used armoured cars to try to break through and fired CS gas – the first time it was used in Ireland. But they failed to penetrate the barricades at the flats. The tricolour and Starry Plough (emblem of the 1916 Easter Rising) were flown from the roof of Rossville flats. The Bogside was impregnable to the police. It was an insurrection. Free Derry was now well and truly born.

As the battle went on, mass rallies were arranged for other nationalist areas to keep the RUC at full stretch. There were battles everywhere with the most serious violence taking place in Dungannon and Belfast. The government refused to pull the RUC back from the Bogside. On the 13 August, a senior army officer on the streets of Derry told General Freeland, the British Army Commander, that the police could not possibly contain the Bogside for more than 36 hours. By the 14 August, the RUC were exhausted and beaten. At 3pm, Chichester-Clark requested British troops. At 4.30pm, Wilson and Callaghan agreed. And at 5pm, the British army rumbled over Craigavon Bridge across the River Foyle into the heart of Derry. The British Labour government had sent troops to aid the ‘civil power’ in the Six Counties. It was intended to have one and only one effect – to support loyalist supremacy, the basis of British imperialism’s continued rule in Ireland. The introduction of the troops was the recognition of the fact that the Six Counties statelet was unreformable and that the nationalist resistance could not be bought off.

David Reed

September 1981

Continued in Part Eight

[Material from this article later went on to become part of Ireland: the key to the British revolution by David Reed]