Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! no. 17, March 1982

The fall of Stormont in March 1972 changed little. The Provisional IRA knew that direct rule from Westminster would not satisfy the needs of the nationalist minority. And as Sean Mac Stíofáin later said

‘. . . there was not an iota of difference, of course, in the behaviour of the British troops towards the people who were supposed to be receiving all the imaginary benefits of direct rule. A rifle butt in the stomach or an insult to passing women felt much the same along the Falls, whether the troops delivered it under Faulkner or the new Secretary of State, Whitelaw . . . It was not the pundits who had to trek out to the concentration camp at Lisburn, taking children to see their fathers after long waits and humiliating jeers from the camp guards.’

The Provisionals’ military campaign would continue until Ireland was free from British rule.

British imperialism still faced the acute problem of drawing support away from the Provisionals. The fall of Stormont had led to a clamour from the SDLP, the Dublin government and the Catholic Church for the IRA to cease military operations. The British government knew it had to build on this. It had to undermine the unity of the nationalist minority if it was to destroy the Provisional IRA. For it was the Provisionals who posed the only serious threat to British imperial-ism’s continued domination over the whole of Ireland.

To undermine the unity of the nationalist minority, the British government continued with the age old imperialist technique of the ‘carrot’ and the ‘stick’. It would attempt to buy off the bourgeois nationalists of the SDLP and their supporters with the ‘carrot’ of power-sharing and the status and privileges of office which went along with this. The nationalist minority, however, would be ‘discouraged’ from continued support for the Provisional IRA by finding itself at the receiving end of a great deal of official and ‘unofficial’ British government directed ‘stick’. Internment without trial would continue, later being replaced by judicial internment – systematic torture in police cells, long remands, Diplock courts and imprisonment in specially built concentration camps. British army and RUC terror and harassment of the nationalist minority, including the use of under-cover assassination squads, were to be regulated to the degree and extent the overall situation required. And when not facing the full force of official British state terror, the nationalist minority had to confront the ‘unofficial’ terror of loyalist paramilitary organisations. Finally, throughout this whole period, there was a barrage of lies and propaganda from both official and ‘unofficial’ British sources, directed against the Provisional IRA.

Truce

In April and May, the Provisional IRA campaign intensified with sabotage operations against ‘the colonial economic structure’ and attacks on the British army and security forces. 40 bombs were planted on the 13 and 14 April, hitting car showrooms, telephone exchanges, a bus station and other business premises. The big Courtaulds factory at Carrickfergus was bombed on 1 May and the Belfast Co-op, the biggest department store in the city, was blown up and destroyed on 10 May. The use of the car bomb increased. During April and May, sixteen British soldiers were killed in the Six Counties.

Early in May, Republican prisoners in Crumlin Road gaol went on hunger strike to back up their demands for political status. Five started the strike and they were to be joined by five more each week until the issue was decided. The leaders of the strike were the popular Provisionals Billy McKee and Proinsias MacArt, who had been sentenced to three years imprisonment having been framed by the army on an arms charge. As the strike progressed, meetings and demonstrations took place throughout the Six Counties. Tension built up in Republican areas and street fights with the army and police frequently occurred.

In the South, the Fianna Fáil administration went on the offensive against the IRA. After people in the Irish Republic overwhelmingly voted to join the Common Market against Republican advice, Lynch felt himself strong enough to directly attack the IRA. He introduced an Emergency Bill to enable civilian prisoners to be transferred to military custody, after Republican prisoners had taken over the inner section of the Mountjoy gaol on 18 May and released scores of prisoners in protest against prison conditions in the gaol. He followed this, at the end of May, with the reintroduction of part V of the Offences Against the State Act, which allowed the setting up of Special Courts consisting of three judges sitting without a jury. After raids by the Gardai and Special Branch, leading Provisionals, including Ruairi O’Bradaigh and Joe Cahill, were arrested. They were released after a hunger strike of thirteen and nineteen days respectively. The Provisional IRA GHQ were forced underground. Many Provisionals, however, were to be arrested and imprisoned after passing through these Special Courts.

Throughout this period, pressure for an unconditional ceasefire by the IRA came from mainly middle-class Catholics, the Dublin government and Church leaders. Speeches, meetings, protests along these lines, however insignificant, were given great publicity by the pro-British, pro-Unionist media. These protests received an enormous propaganda boost after the Official IRA executed Ranger William Best, a young local Derry man home on leave from the British army. He was stationed in Germany with the Royal Irish Rangers, one of the regiments the British could not trust for work in the Six Counties. Mac Stíofáin says that the Provisional IRA had information that Ranger Best had frequently been out at night stoning British troops and that he was not going to return to his base in Germany. Mac Stíofáin thought that the Official IRA must surely have been told this when they took him away.

There was bitter reaction to the killing in the Bogside and angry local women took over the headquarters of the Officials and formed a ‘movement for peace’. The Church, press and television used the occasion to whip up anti-IRA hysteria. The ‘peace at any price’ brigade was reinforced by these developments. There were, however, large counter-demonstrations against this ‘peace’ movement, including a very large one by Provisional volunteers and supporters, but the calls for a ceasefire by political opportunists of all kinds inevitably increased. As Mac Stíofáin, with some justification later said, ‘this stupid killing had given them (the political opportunists) a chance to promote division and dissension in the midst of the most successful no-go area in the entire North’.

The pressure for a one-sided ceasefire by the IRA built up. Peace pickets paraded outside the Sinn Féin offices in Kevin Street, Dublin. While the Provisionals and their supporters stood firm in the face of this pressure, the Official IRA did not. On the evening of 29 May, the Official IRA announced that it would terminate all military action. No terms were mentioned. Since ninety per cent of all operational, activities were carried out by the Provisional IRA, the overall effect of the decision was insignificant. The popularity and political base of the Official IRA was not strengthened. The Provisional IRA was able to intensify its campaign and during the next four weeks casualties suffered by British troops were the biggest for any month since the start of the campaign. During May, according to British figures, there were 1,223 engagements and shooting incidents and ninety-four explosions. The sabotage operations were increasingly disrupting the day-to-day functioning of direct rule. As June began, the IRA stepped up the level of its offensive.

In the second week of June, a new and more serious peace proposal was put before the IRA leadership. It came from Republican activists in Derry and had the agreement of the local IRA military leadership. It was that the Provisional IRA should hold a press conference inside the Free Derry area and agree to suspend offensive operations for a seven-day period provided that Whitelaw agreed publicly to meet the IRA. The proposal was a good one. It gave an opportunity for the Provisionals to put their terms for a peace settlement formally to the British government. It offered a truce that was not unconditional, not one-sided and not for an indefinite period. From the military standpoint, it was a good time as the Provisional IRA were strong and were causing a great deal of damage and disruption to the economic life of the Six Counties. Finally, it shifted the whole responsibility for a peace settlement back where it belonged, in the court of the British government. For, if the British now refuse, it would show millions of people that the British government was more interested in destroying Irish resistance to British rule than in a peaceful settlement.

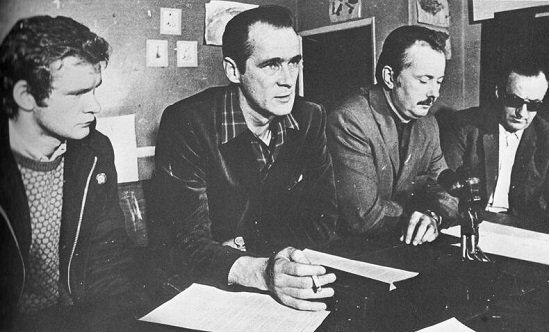

The Provisional IRA leadership agreed to accept the proposal. On Wednesday 13 June, Sean Mac Stíofáin, David O’Connell, Seamus Twomey Martin McGuinness gave a press conference in the no-go area of Free Derry and announced their offer of a truce.

Whitelaw responded quickly. He issued a statement that same evening rejecting the truce offer on the grounds that he ruled out any meetings with ‘terrorists’. However, at the time of the press conference it emerged that Whitelaw had personally received members of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) inner council in a meeting held at their request. The men had arrived at Stormont Castle, hooded and masked, and wearing sun glasses. So Whitelaw was prepared to meet leaders of the UDA, a loyalist paramilitary organisation, which was directly responsible for the campaign of sectarian murders of Catholics which had begun in the Spring of 1972 (see below). It appeared that he was not prepared to meet the legitimate leaders of the nationalist minority.

After the failure of this public approach. two SDLP members, John Hume and Paddy Devlin suggested to the IRA that they should approach Whitelaw and make it clear to him that the IRA were serious about a truce. This was agreed.

They came back saying that Whitelaw would like a meeting with the Provisional leadership but this was ‘not possible immediately’. However, a preliminary meeting held in secret with members of Whitelaw’s staff was suggested. In reply, the IRA laid down four conditions if there was to be a meeting to discuss a truce. The first was the granting of political status for Republican prisoners in the Six Counties, some of whom had been on hunger strike now for nearly five weeks. Second, there were to be no restrictions on the choice of Republican representatives – the British to accept those nominated. Third, Stormont Castle was not an acceptable venue. Finally, the meeting was to be confined to the British representatives and the Provisional IRA (the SDLP had tried to get in on the act) with a mutually acceptable third party, who would not be a politician, to act as a witness. David O’Connell and Gerry Adams were nominated as representatives – the latter being at that time under detention in Long Kesh. John Hume took the terms back to Whitelaw and he accepted them all. As Mac Stíofáin later said, ‘within hours of publicly refusing to treat with terrorists, the British were secretly agreeing to discuss a truce with us’.

Gerry Adams was released from Long Kesh and an announcement was made that the political prisoners would be given political status – called ‘Special Category’ status. This included the right of political prisoners to wear their own clothes, the right to abstain from penal labour, the right to free association, the right to educational and recreational activities and the restoration of lost remission resulting from the prison protest. The hunger strike ended. The Special Category status was also given to UVF and other loyalist prisoners.

On 20 June David O’Connell and Gerry Adams met Whitelaw’s two representatives Philip Woodfield and Frank Steele at a secret meeting place outside Derry. There they agreed to a bilateral truce with hostilities ceasing on both sides. The IRA were to enjoy freedom of movement on the streets and the right to bear arms, as were the British. There were to be no arrests, raids, searches of persons, homes and vehicles. After ten clear days of the truce being effective, a secret meeting between the Provisional IRA and Whitelaw would take place to discuss the IRA’s conditions for ending operations altogether.

A statement was issued on Thursday 22 June announcing that the Provisional IRA would suspend offensive operations from midnight Monday 26 June provided that a public reciprocal response was forthcoming from the Armed Forces of the British Crown. Whitelaw announced that the British forces would reciprocate.

Republican intelligence – including that from a highly effective telephone tapping operation – had reported that high-ranking RUC officers and senior British army personnel had been saying that the IRA had agreed to talks because they were on their last legs. The IRA leadership decided to make it abundantly clear to all concerned that they were not negotiating from a position of weakness. All IRA units were instructed to continue in action up to the final minute of the agreed truce. In the period leading up to the truce, four British soldiers and an RUC man were killed, the last soldier being shot at 23.55 hours on Monday, five minutes before the truce was to begin. At midnight Monday 26 June 1972, all IRA operations ceased and the truce began.

A week after the truce started, the British had still not informed the Provisional IRA of the arrangements for the meeting with Whitelaw. The IRA then contacted the British representatives by telephone, using agreed numbers, and after some haggling by the British, a meeting was arranged for Friday 7 July in London.

On that date the Provisional IRA leaders Sean Mac Stíofáin, David O’Connell, Seamus Twomey, Martin McGuinness, Gerry Adams and Ivor Bell were flown to London for the secret meeting with William Whitelaw and other British government officials. Two of the Provisional IRA delegation carried arms. Myles Shevlin, a Dublin lawyer, joined the meeting acting as secretary to the IRA delegation.

They met Whitelaw in a private house in Chelsea belonging to Paul Channon, heir to the Guinness fortunes and one of Whitelaw’s junior ministers. This was the first time that representatives of the IRA had fought their way to a conference with the British for over fifty years. This fact alone confirms that the imperialist propaganda about ‘isolated gunmen’ was, and is, a straightforward lie. The fact that the British felt obliged to negotiate with the IRA was proof that the IRA had the volunteers, the equipment and the mass support to wage war for as long as necessary.

At the meeting, the Provisional IRA delegation placed a number of demands before the British government for negotiation. They were that:

- The British government recognise publicly that it is the right of the people of Ireland acting as a unit to decide the future of Ireland.

- The British government declare its intention to withdraw all British forces from Irish soil, such withdrawal to be completed on or before the first day of January 1975. Pending such withdrawal, the British forces must be withdrawn immediately from sensitive areas.

- A call for a general amnesty for all political prisoners in Irish and British jails, for all internees and detainees and for all persons on the wanted list. In this regard, dissatisfaction was expressed that internment had not ended in response to the IRA initiative in declaring a suspension of offensive operations.

There were two clashes between the two sides at the meeting. The first was when Whitelaw had the effrontery to say that British troops would never open fire on unarmed civilians. He was promptly and forcefully reminded of Bloody Sunday, and told of several other occasions when this had occurred. The second concerned all-Ireland elections to decide the future of Ireland. Whitelaw brought up the ‘constitutional guarantees to the majority in Northern Ireland’. He was told that it was the Government of Ireland Act 1949, passed in the British House of Commons, which guaranteed the constitutional position. And any Act of Parliament could be set aside by another through a simple majority in the same House of Commons.

Whitelaw was given a week to raise the demands with the Tory Cabinet and give an answer to them at a meeting planned for 14 July. The truce was now open-ended with each side to give 24 hours’ notice of intention to break it. Whitelaw agreed. He was told that the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) had already violated the truce agreement by setting up roadblocks and searches. He agreed to do something about this. Whitelaw also said that the sectarian assassinations and intimidation of Catholics by loyalist paramilitary organisations – there were to be 18 sectarian murders by loyalist organisations during the fourteen days of the truce – would be brought to an end and Catholics in UDA ‘no-go’ areas would be protected by the British army. Finally, further contact was to be made through his officials and the meeting was to remain secret.

An off the cuff remark by one of Whitelaw’s officials on the flight back to Belfast exposed the attitude of the British ruling class to the lives of British soldiers. Frank Steele, when discussing a possible resumption of the war, said ‘Don’t think you’re worrying us with the casualties you’re causing our troops at the moment . . . we lose more men through road accidents in Germany in any one year than the losses you fellows are inflicting on us’. That twenty British soldiers had been killed and many injured in the last three weeks was of little concern to him and the ruling class he represented.

British imperialism breaks the truce

The truce was to last only two more days. The British did nothing about the sectarian assassinations and allowed the UDA to put up barricades in parts of Belfast while bulldozing nationalist ones down in Portadown. Two British army captains who had been detained by IRA volunteers after penetrating Free Derry the night before the London meeting, had been released the next day. However, two IRA volunteers from Belfast who had been arrested, in spite of telephone calls to the British representatives, were still detained two days later. The matter finally came to a head on the Lenadoon housing estate in West Belfast

A few Catholic families who had lost their homes or had been forced to move through intimidation were allocated empty houses on the Lenadoon estate – a mixed estate. The UDA brought reinforcements into Lenadoon from outside areas and informed the British army that if Catholics moved into the houses, they would be burned out. The British army commander gave into UDA threats not allowing any more Catholic families to take up the homes allocated and so overriding the civilian authority – the Northern Ireland Housing Executive. The British army then barricaded the area. People and cars in the area were stopped and roughly searched while UDA men, some carrying arms, stood behind the British troops and looked on and jeered. When on Sunday 9 July a ten-ton British armoured car rammed a lorry containing the furniture of some of the families – the incident was televised – an angry crowd of Catholics gathered. They were attacked by troops who fired rubber bullets, water-cannon and CS gas at them. Shots were soon fired. The truce had been broken by the actions of the British army.

Efforts were made throughout the weekend to contact the British representatives and finally Whitelaw himself. When Whitelaw was eventually contacted early on Sunday evening, he said he would look into the crisis. Nothing further was heard from him. The Provisional IRA had no choice. That evening, they announced the termination of the truce and instructions were sent out to all areas to resume operations at once.

An attempt was made by Harold Wilson, then leader of the Labour opposition, to try and get the truce going again. Three representatives of the Provisionals including Joe Cahill, flew to a private air field near Wilson’s home in Buckinghamshire in a chartered plane on 18 July 1972. The talks came to nothing when it became clear that Wilson was not speaking on behalf of Whitelaw or the British government. Wilson never made any attempt to negotiate with the Provisionals again. No doubt when he had the power and authority to do so, his real intentions would have easily been exposed.

An imperialist government will not negotiate with representatives of a revolutionary movement without being under enormous pressure to do so. The IRA had been inflicting serious casualties on the British army and substantial damage to the Six Counties economy. Until the truce, the British had been using the people’s desire for peace for their own propaganda campaign against the IRA. When this was exposed with a serious offer of a truce and peace negotiations by the Provisional IRA, the British had little choice but to go through the motions of acting on it. The Provisional IRA had also distributed their democratic programme Eire Nua just after the truce began. They had nearly 300,000 copies printed in English and Irish. This programme included religious and political guarantees and rights for the Protestant minority in a United Ireland and proposed four regional Parliaments including one for the nine counties of Ulster. It amounted to a serious peace proposal which could not simply be ignored.

The ending of the truce by the British government was deliberate. They needed only some pretext to do so. The dispute at the Lenadoon housing estate served their purpose. The British government built up the hopes of the nationalist minority only to smash them down again. The nationalist people wanted peace. The British wanted only to destroy the IRA – the only force to challenge their rule over the whole of Ireland. The British refused to take on the UDA and curb the loyalist assassination squads because it served their purpose not to do so.

Within a day of the truce ending, the British shot six civilians dead. In Ballymurphy this included a boy and a girl of thirteen. As the boy lay dying in the road, an elderly priest went out to him and was also shot dead. The UDA and other armed loyalists joined behind British troops in attacking nationalist areas. Many Catholic women and children fled to the South as refugees. And all the while the loyalist assassination squads continued their brutal work murdering another 13 Catholics before the end of July.

The IRA hit back hard and the British paid very dearly for destroying the truce. In the first eight days after the truce ended, the British lost at least 15 soldiers killed and over a hundred injured. In the next two weeks, they lost another ten dead. The sabotage offensive was renewed. One of its principal aims was to tie down as many British troops as possible on guard duties in the cities and towns, keeping them off the backs of the nationalist population and from being used against IRA units in rural areas. On Friday 21 July a major bombing offensive took place with 22 operations in Belfast in a period of 45 minutes within a one-mile radius of the city centre. There were 13 operations elsewhere in the Six Counties. In all cases warnings were given. But in two places in Belfast, Cavehill Road and Oxford Street, they were ignored. Nine people were killed – two were British soldiers, of the other seven one was a RUC reserve policeman, another a member of a militant loyalist organisation and five were civilians. Many people were injured.

Statements were immediately put out by the Belfast Brigade IRA accepting responsibility for the bombs, saying that warnings had been given in all cases, and that responsibility for loss of life rested with the British who failed to pass the warnings on. At first the British put out a statement, and Whitelaw stated on television, that in the two cases no warnings were given. Later this was retracted when undeniable evidence to the contrary was produced. The Samaritans, the Public Protection Agency and the Press were informed of the bomb positions at least 30 minutes before the explosions. The Irish News later said that they had confirmed with the agencies concerned that the warning of a bomb in Cavehill Road was given an hour and 13 minutes before the blast, and in Oxford Street 30 minutes before it happened. In both cases, the information had been immediately passed on to the security forces. The Republican Movement was convinced that the British had deliberately disregarded these two warnings in order to weaken support for the IRA among the nationalist population. In a pamphlet ‘Friday – the Facts’, put out by Sinn Féin a week after the bombings, after explaining what had happened they then reminded the nationalist minority,

‘The Republican Movement, unlike the British, always admits the truth whether it is distasteful or not. We do not cloud the issue by false reports based on half-truths. For years now English politicians have told lie after lie about events in Northern Ireland. These run in a long list – the Widgery report, the Compton report and now “the Whitelaw Report”, a report of events as distorted as all the others.

No one who has studied the situation in the last three years can deny that the British are liars, with the intention of splitting the people. When has the Republican Movement lied to the people? Why should they lie to the people? The people are the Republican Movement. We extend sincere sympathy to the relatives of those who died so needlessly.’

Over the next few days, British troops launched attacks on five nationalist areas in Belfast and gun battles took place. On 27 July an increase in the number of British troops in the Six Counties of 4,000 to 21,000 was announced. On the 30 July, Whitelaw issued a statement that there would be ‘substantial activity’ by security forces in various parts of the Six Counties and he advised people to keep off the streets.

There had been a great deal of British and Unionist propaganda about the unacceptability of the no-go areas in Derry and Belfast over recent weeks. It was clear that the aftermath of the tragedy of the bombings in Belfast was going to be used by the British as an opportunity to launch an attack on these areas. No doubt the British hoped that the Provisional IRA would come out into the open to defend them.

The Provisional IRA had no intention of a static defence of these areas against what would be a strong armoured British force. As Mac Stíofáin later made clear, it ‘would have been completely contrary to all the principles of guerrilla warfare’. So that when ‘Operation Motorman’ began and thousands of extra troops and many hundreds of armoured vehicles moved at 4.30am on 31 July into Free Derry and the Belfast no-go areas, they met with no resistance from the IRA. In fact, the troops were often sitting targets as their huge heavy tanks and other vehicles got stuck in the tiny streets and British officers ran up and down shouting at the drivers. But, given the troop concentrations, to start a shooting match could only have led to serious casualties among the civilian population. As it was, the British killed two young men as they came into Derry and showed typical imperialist arrogance by commandeering schools and community centres and using them as barracks. The no-go areas were down but the IRA remained intact.

The same day, three ear bombs exploded in the village of Claudy, Co Derry, killing six local people and injuring many more. The IRA were, of course, blamed but they completely disclaimed responsibility. In a statement on the bombings, the IRA pointed out that ‘such actions can only suit the British Military to divert attention away from their mass invasion of nationalist Derry, Belfast and other towns’. Later, information which came out concerning the undercover activities of the Littlejohn brothers for the British security forces, showed only too clearly how the British were using agents provocateurs and other freelance groups for their own propaganda ends.

The events since the truce ended – the casualties inflicted in Belfast when the bomb warnings were not passed on – allowed the British to go on the offensive. From now on, there would be no discussions with the IRA.

The British government now began a period of political manoeuvring to isolate the IRA and undermine its support in the nationalist minority. But to do this, it needed to offer the anti-IRA sections of the minority a viable alternative. However, such an alternative, promising once again to reform the Six Counties statelet, would meet the inevitable opposition from the organised loyalist forces which were determined to defend the privileges and status of the Protestant majority.

The rise and fall of power-sharing

The SDLP had been pushed off the political stage ever since they were forced to leave Stormont in July 1971 (see FRFI 15). Since the fall of Stormont they had been using every opportunity to worm their way back again. On the 25 May 1972, an ‘Advisory Commission’ was announced consisting of 11 persons ‘fully representative of opinion’ in Northern Ireland (ie middle class opinion) to assist the Secretary of State in his duties. Next day, the SDLP offered a ‘positive response’ to what Mac Stíofáin aptly termed ‘Whitelaw’s latest colonial reform stunt’. The SDLP urged those who had withdrawn their support from public bodies after internment to return to their positions ‘to demonstrate their determination to bring about community reconciliation’. However, conditions were still not ripe for the SDLP to have formal negotiations with William Whitelaw and the British imperialist administration. Some more bait would be necessary and some move on internment before the craven opportunists of the SDLP would feel safe to conduct their betrayal of the nationalist minority more publicly.

On 15 July, two days after the Provisionals’ press conference in Free Derry offering a truce, Whitelaw announced he proposed to hold a ‘conference of the people of Northern Ireland’ on the future of the province and further that local government elections would be held on the basis of proportional representation. The imperialists were dangling their bait. After the truce was over, and after the effects of the tragic deaths in Belfast on 21 July, the SDLP began to bite.

On 7 August after consultations with Dublin, the SDLP held their first meeting with Whitelaw. Internment, security, army searches, and the occupation by troops of schools in nationalist areas were some of the topics raised. After the meeting, the SDLP issued a statement saying that the release that day of another 47 men from Long Kesh camp was not adequate and they called for a complete end to internment. There were still 283 men interned. In the meantime they urged their constituents to continue with their ‘admirable restraint in the present situation’. Two days later, during demonstrations and protests on the first anniversary of the introduction of internment, effigies of SDLP members Gerry Fitt and Paddy Devlin were burned on the Falls Road.

On 3 August Whitelaw had had talks in London with the Irish Foreign Minister. On 4 September Lynch met Heath at the Munich Olympic Games. During the talks, Heath raised the matter of ‘IRA bases’ in the 26 Counties ‘from which raids into Northern Ireland could be mounted’. It would not be long before Fianna Fáil would comply with their colonial masters’ demands to remove them. On 12 September the SDLP met Heath and Whitelaw in London and during discussions they informed him that they could not attend the planned ‘Conference of the People of Northern Ireland’, scheduled for 25 September in Darlington, Co Durham, as no agreement had been reached on the ending of internment. The conference took place and predictably produced nothing since the SDLP did not attend. The British government would need to offer a tiny bit more before the SDLP would feel able to do its bidding. More secret meetings between the collaborating parties took place and negotiating positions were laid down. On 20 September, the SDLP produced a policy document Towards a New Ireland which called for dual British-Irish sovereignty over the Six Counties and a British declaration in favour of eventual unity of Ireland.

On 30 October 1972 the British government produced a Green Paper – The Future of Northern Ireland, a paper for discussion. They also announced that the border poll – promised when Stormont was suspended – would take place in Spring 1973. The Green Paper contained the usual and fundamental commitment to maintaining the existence of the sectarian statelet:

‘The guarantee to the people of Northern Ireland that the status of Northern Ireland as part of the United Kingdom will not be changed without their consent is an absolute: this pledge cannot and will not be set aside.’

But the Green Paper warned with a cynical frankness that

‘ . . . there is no hope of binding the minority to the support of new political arrangements in Northern Ireland unless they are admitted to active participation in any new structures.’

At last, this offered the ‘carrot’ the SDLP had been longing to bite. For the Green Paper went on to say that there were

‘ . . . strong arguments that the objective of real participation should be achieved by giving minority interests a share in the exercise of executive power.’

The Dublin government was also given a cover for its collaboration with British imperialism. The Green Paper, with typical imperialist arrogance, made a gesture towards recognising the ‘Irish dimension’ in the Six Counties problem:

‘A settlement must also recognise Northern Ireland’s position within Ireland as a whole . . . It is therefore clearly desirable, that any new arrangements for Northern Ireland should, whilst meeting the wishes of Northern Ireland and Great Britain, be so far as possible, acceptable to and accepted by the Republic of Ireland.’

For, as the Green Paper went on to say, and in this it expressed a fundamental interest which British imperialism, the Dublin government and the SDLP shared in common, such a settlement would

‘provide a firm basis for concerted governmental and community action against those terrorist organisations which represent a threat to free democratic institutions in Ireland as a whole.’

This was the key factor in the whole strategy. The Green Paper recognised that the political and military struggle of the Provisional IRA not only threatened the stability of the neo-colonial and colonial regimes in the 26 Counties and Six Counties respectively, and therefore British imperialist rule over Ireland, but also the capitalist system – ‘free democratic institutions’ – in Ireland as a whole.

The aim of British imperialism was to destroy the IRA. In an attempt to isolate the IRA, British imperialism was prepared to offer a share of political power, status and privilege to the Catholic middle class through its political mouthpiece, the SDLP. While less immediate, the IRA also represented the only serious threat the neo-colonial government in the 26 Counties. The Green Paper allowed the Dublin government to put across its collaboration with British imperialism as a realistic step towards reunification of Ireland. On 24 November Lynch met Heath in London and spoke of a ‘closer meeting of minds than he had ever experienced before’, clearly indicating his agreement with the Green Paper. The next day the SDLP annual conference voted overwhelmingly to enter into talks with William Whitelaw on the future of the Six Counties – so breaking their pledge not to talk until internment was ended. The stage was now set to implement this latest phase of British policy.

Towards the end of September 1972 there were a number of petrol bomb attacks by unknown men on Gardai (police) stations in the 26 Counties near the border. A large bomb was also found in Dundalk Town Hall and defused amidst a barrage of publicity. There were also a series of bank robberies. All these activities were immediately blamed on the IRA and intensive police and Special Branch activity against Republicans followed. In early October a group of armed men raided a branch of Allied Irish Banks in Grafton Street, Dublin. They got away with £67,000. At their trial in July 1973, the Littlejohn brothers claimed they had committed the robbery to bring about legislation in the 26 Counties against subversive movements. They also later claimed that all their work, including the bomb attacks, had been carried out with the full consent of the Ministry of Defence. They had been acting as agents provocateurs for British intelligence. Other British agents were also at work in the 26 Counties and one of them, John Wyman, was later tried in an Irish court in February 1973.

Lynch’s Fianna Fáil government was all too ready to play a central role in ‘governmental and community action against those terrorist organisations’ considered a threat to it. The background of bombings and bank raids offered the excuse. Already on 6 October, the Dublin government had closed down without warning the Provisional Sinn Féin headquarters in Kevin Street, Dublin and another building in Blessington Street housing northern refugees.

On 5 November Maire Drumm, Vice-President of Sinn Féin, was arrested and given a short prison sentence. On 19 November Sean Mac Stíofáin was arrested and charged with being a member of an illegal organisation. He immediately went on hunger and thirst strike demanding his release. After a farcical trial, during which a Radio Telefis Éireann (RTÉ) journalist was sentenced to three months imprisonment for refusing to identify Sean Mac Stíofáin’s voice on a tape being used as evidence, Sean Mac Stíofáin was sentenced to six months imprisonment. During his arrest, trial and subsequent imprisonment, there were massive demonstrations and one attempt to free him. After ten days and very close to death he gave up his thirst strike to avoid the inevitable bloody conflicts in the 26 Counties which would follow his death. In a message sent out he argued that the fight is centred in the Six Counties and must be kept there. After 59 days he gave up his hunger strike having been ordered off by the leadership of the IRA and in Spring 1973 he was released. Seamus Twomey replaced him as Chief of Staff of the IRA.

On 24 November the Dublin government dismissed the entire governing body of RTÉ for broadcasting the interview with Mac Stíofáin. Another bomb went off in the centre of Dublin on 25 November causing serious damage and injuring 40 people. The Provisional IRA denied responsibility for the explosion. On 27 November the Dublin government announced details of a new draconian amendment to the Offences Against the State Act under which the evidence of a Gardai Superintendent that he believed someone to be a member of the IRA or any illegal organisation would be sufficient to convict. There was widespread opposition to the Bill even from Labour and Fine Gael. It looked as if the Bill would not be passed when two huge bombs exploded in the centre of Dublin on Friday 1 December killing two men and injuring nearly 100. In a wave of anti-IRA hysteria, the Bill was passed on Saturday morning 2 December at 4am by 70 votes to 23. Fine Gael deputies voted in favour.

The Provisional IRA categorically denied responsibility for the explosions and it was widely thought that the bombs were planted by Loyalists or British agents to influence the vote in the Dáil. With a system of judicial internment now in force, the gaols in the 26 Counties rapidly filled up with revolutionary Republicans, including Ruairi O’Bradaigh and Martin McGuinness.

The Provisional IRA and their supporters were hard hit by repression and arrests both sides of the border. In the Six Counties sectarian assassinations increased with the vast majority of them carried out by Loyalist paramilitary organisations such as the UDA and various offshoots of that same organisation. These loyalist groups instituted a campaign of random and brutal terror directed at Catholics, involving particularly ghastly murders after the sadistic torture of the victims. There were 40 sectarian killings in the last four months of 1972 and 31 of the victims were Catholics. A number of these killings were later found to have been carried out by the British army. Hardly any of the Catholics murdered in this way had any connections with the Republican Movement.

It was only after Operation Motorman was over and the British government was trying to create a political settlement acceptable both to the Catholic middle class in the Six Counties and the Dublin government, that the British showed a little less toleration of the activities of loyalist paramilitary organisations. A gun battle between the British army and the UDA took place in September 1972 and a UDA gunman – who was also a member of the UDR – was killed. Other clashes took place in October. In February 1973, after more brutal murders of Catholics – 5 in two days – 2 Loyalists were arrested and interned. They were the first loyalist internees for 50 years. The UDA reacted with fury and a number of heavy gun battles with the army took place. However, in spite of all this, the UDA was never banned by the British government. The number of loyalist internees in Long Kesh did, however, increase to 60 by mid-1974, compared with 600 Republicans. All were released by April 1975 when there were still over 350 Republicans interned, some having been there since 1971.

The nationalist population in the Six Counties was becoming more and more divided along class lines. The Catholic middle class desperately wanted peace and clutched at the Green Paper as offering real prospects for progress – their progress. The working class in the nationalist areas, still at the receiving end of internment, British army brutality and loyalist terror squads, knew that progress for them was not possible until loyalist supremacy, and therefore British rule in Ireland, was ended. They supported the Provisional IRA. So, despite the harassment and arrests on both sides of the border, the Provisional IRA had the support necessary to continue their campaign.

In the four months since Operation Motorman, British government statistics said there had been 393 explosions and 2,833 shooting incidents. In December 1972, there were 48 explosions and 506 shooting incidents including rocket and mortar attacks. At the end of November, the IRA had begun using new Soviet RPG 7 rocket launchers with devastating effect. All this was happening in spite of army claims to have arrested 500 people including ‘200 Provisional IRA officers’ since Operation Motorman at the end of July 1972.

On Monday 25 September 1972, the day of the Darlington Conference, the Provisional IRA blew up Belfast’s newest luxury hotel, the Russell Court, causing over £2 million damage. On 2 October, on the Twinbrook Estate in Belfast, an IRA unit executed three members of a British army undercover squad, who were operating in Republican districts disguised as laundry service employees and travelling in a Four Square laundry van. Two others were killed in a flat on the Antrim Road, a massage parlour used by the ‘laundry men’ as their HQ. The British only admitted one of their agents had been killed on that day. These squads were a practical application of Brigadier Kitson’s theory of counter-insurgency operations. It was already known that SAS type undercover squads had been in operation in the Six Counties for some time. Their operations were stepped up in September 1972, and using unmarked cars, they were involved in attempts to assassinate not only Republicans on a ‘hit-list’ but Catholic civilians as well. They often carried guns likely to be used by IRA units, so that having killed someone they could lay the blame on the IRA. No doubt they saw this as a means to create inter-Republican clashes and sectarian feuds. These Military Reconnaissance Force (MRF) squads hit problems early in 1974 when an RUC patrol shot two MRF men dead in an old van in South Armagh because they were acting suspiciously.

The Provisional IRA called a Christmas truce and ceased all but defensive actions for three days. The year 1972 had seen 10,628 shootings, 1,495 explosions, 103 British soldiers killed, 43 RUC/UDR men killed and 321 civilians killed. Since December 1969, the Provisional IRA had lost 75 volunteers killed while thousands had suffered torture and imprisonment. The New Year Statement from the IRA pledged that the struggle would continue ‘as long the British government persists in its policy of military repression’.

The British government had another weapon in its armoury of repression. On 20 December 1972, the Report of the Diplock Commission was published and its recommendations accepted by the British government. It was set up in October 1972 to consider

‘. . . what arrangements for the administration of justice in Northern Ireland could be made in order to deal more effectively with terrorist organisations by bringing to book, otherwise than by internment by the Executive, individuals involved in terrorist activities, particularly those who plan and direct, but do not necessarily take part in, terrorist acts; and to make recommendations.’

Diplock’s recommendations were a fundamental assault on basic civil liberties. They removed trial by jury for scheduled offences – ie those associated with ‘terrorist’ activities, a very broad category in the Six Counties. These would be heard by a Judge sitting without a jury. Most judges in the Six Counties were openly associated with the Unionist party. The onus of proof as to the possession of firearms and explosives was changed so that the accused had to prove he/she was innocent. A confession made by the accused should be admissible as evidence provided the court was satisfied that on balance of probability they were not obtained by torture or inhuman or degrading treatment. Bail for scheduled offences should not be granted except by the High Court and only then if stringent requirements were met.

The recommendations were incorporated in the Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act 1973 which became law on 25 July 1973 and came into force on 8 August 1973. They became the basis of judicial internment – the ‘conveyor belt’ system that was designed to give internment a thin veneer of ‘respectability’ – systematic torture in police cells to obtain ‘voluntary’ confessions, long remands, Diplock courts, imprisonment in the H-Blocks and Armagh Prison. With the Gardiner Report 1975 removing ‘Special Category’ status, the basis was laid for the ‘criminalisation’ policy administered by the Labour government. But all that was to come later.

The British government pushed ahead with its plans. On 8 March 1973 the referendum on the border was held. It was boycotted by all anti-Unionist groups including the SDLP. The boycott was remarkably effective; 41% of the electorate abstained. The result of the poll was a foregone conclusion. 591,820 votes or 57% of the electorate voted to remain part of the UK and only 6,463 voted for the alternative of unity with the 26 Counties. The IRA reinforced its attitude to the border poll when it carried its campaign to England. Car bombs went off outside that symbol of imperialist justice, the Old Bailey, and outside Great Scotland Yard. One person died and 180 people were injured. Poll or no poll, the Republican movement wanted a united Ireland. The political impact of the explosions was dramatic in that they, together with the successful boycott campaign, destroyed the propaganda value of the Border poll for British imperialism.

On 20 March 1973 the British government published a White Paper on the Constitutional Proposals for governing the Six Counties. They were based on the criteria laid out in the earlier Green Paper of October 1972. The Stormont parliament and government were to be replaced by an Assembly to consist of about 80 members elected by proportional representation. The Assembly would have committees whose chairmen formed the Executive. The Executive was not to be drawn from a single party but would embody the idea of power-sharing. There would continue to be a Secretary of State for Northern Ireland at Westminster and control of security matters would remain with the British government. A Charter of Human Rights was proposed in the White Paper.

There would be a Council of Ireland for North/South discussion on relevant matters and its form and function would be decided at a conference between London, Dublin and the Northern parties after the election. The White Paper is typically vague and empty on the purpose of the Council of Ireland and the most it offers is a repetition about forms of practical economic cooperation such as tourism, regional development, electricity and transport. But it is very precise on two other aspects of the ‘Irish dimension’. That is the acceptance of all parties, and particularly the Dublin government, of ‘the present status of Northern Ireland’ and ‘the provision of a firm basis for concerted governmental and community action against terrorist organisations’. The last all-Ireland dimension of repression was the one vital element in the Irish dimension which the British government wanted to secure. As the White Paper put it, ‘the Government has no higher priority than to defeat terrorism’. The Catholic middle class had been offered a share in power, the Dublin government given an ‘Irish dimension’ in return for support in the campaign against the IRA and the acceptance of the present constitutional position of the Six Counties as part of the United Kingdom. The IRA put out a statement which summed up the White Paper as

‘. . . a skilful application of Britain’s age old policy of “divide and conquer”. Having failed by military means to break the will of the northern people to be free citizens in a free country, Britain now presents a set of political proposals which is designed to confuse and fragment the nationally-minded community and insult and provoke those who believed in maintaining the connection with England.’

The White Paper led to a split in the loyalist camp. The Grand Orange Lodge condemned the White Paper at the end of April. Craig rejected it as well, and announced on 30 March the formation of a new party, the Vanguard Unionist Progressive Party (VUPP) backed by the UDA and the Loyalist Association of Workers (LAW). This party would fight the Assembly elections in alliance with Paisley’s DUP and in opposition to the White Paper.

The Assembly election took place on 28 June 1973. The Provisional IRA called for a boycott but with little effect. The SDLP put up 28 candidates and got 159,773 votes and nineteen seats, making it the largest anti-Unionist parliamentary group in the history of the sectarian statelet. The anti-White Paper Unionists got 28 seats with Vanguard getting seven seats, the DUP eight seats, the West-Taylor group of Unionists ten seats, and other independent Loyalists three seats. The Faulkner Official Unionists obtained only 22 seats and the Faulkner group itself was very unstable. The anti-White Paper Loyalists had a majority and were totally committed to pressing their case home.

The ‘centre’ of the Six Counties politics almost collapsed. The NILP with 18 candidates won one seat and the Alliance Party – a moderate pro-British Unionist party committed to reforming the Northern state – got only eight seats with Westminster backing.

The Assembly met for the first time on 31 July and after heated wrangles and numerous procedural motions most of the members except the followers of Paisley and Craig walked out. The latter remained to carry out impromptu business and ended proceedings by singing ‘God Save the Queen’.

Meanwhile the Provisional IRA campaign went on with repeated rocket and mortar attacks on British positions and camps. In the first six months of 1973, Provisional IRA operations had expended 48,000 pounds of explosives. In July and August, there were 167 bombs detonated and sniping, cross-border raids, ambushes and other operations continued into the autumn. In August and September 1973, the English bombing campaign took off again with a more extensive use of incendiary devices and small bombs. 1973 saw 58 British soldiers and 22 RUC/UDR men killed.

Repression in the Six Counties continued with the number of Republican internees climbing back towards the pre-direct rule figures. In December 1973 662 men were detained in Long Kesh. In January 1973 women were interned for the first time. Between Operation Motorman, 31 July 1972, and August 1973, the British government claimed that 1,456 people had been charged with ‘terrorist type’ offences, 925 since 1 January 1973. There were now nearly 1,000 sentenced political prisoners in Six Counties gaols. Assassination figures in October 1973 showed 71 had taken place, the vast majority would have been carried out by Loyalists.

In the 26 Counties a new coalition government of Fine Gael and Labour had come to power after Fianna Fáil lost the General Election in February 1973. Repression and harassment of Republicans continued. In March 1973, the Provisionals lost five tons of arms that had come from President Ghadaffi’s Libya. The ship Claudia with Joe Cahill aboard was picked up in Irish territorial waters and six men were arrested and charged with smuggling arms. There were some victories. On 3 October, the sixty Republican prisoners won ‘special status’ after a hunger strike of 20 days. On 31 October a spectacular prison escape took place when a hijacked helicopter landed in the exercise yard of Mountjoy gaol and rescued three leading Provisionals, including Seamus Twomey.

After the June Assembly elections in the Six Counties, Whitelaw and the British spent months trying to persuade the Unionists around Faulkner and the SDLP to share power in a coalition government. But the middle ground was inevitably slipping away. Heath came to Belfast at the end of August and warned the party leaders to form an Executive very quickly. In September Whitelaw had separate talks with the three parties who broadly supported the White Paper – SDLP, Faulkner Unionists and the Alliance. Heath also met the new 26 Counties Taoiseach Cosgrave and urged the Dublin government to put pressure on the SDLP to reach an agreement.

On 5 October 1973 an agreement in principle was made by the three parties to form an Executive. The SDLP accepted that there would be no change in the status of Northern Ireland until a further border poll in ten years’ time. On 20 November, an anti-power sharing motion was narrowly defeated by only ten votes et the 750-strong Ulster Unionist Council. Things didn’t look very promising. Yet on 22 November 1973 a definite agreement to form an Executive was made. Faulkner was to be Chief Executive, Fitt his deputy and there would be six Unionists, four SDLP and one Alliance in the 11 person Executive. There would also be a London-Dublin-Belfast conference as soon as possible to settle details for a Council of Ireland.

The anti-White Paper Loyalists were furious with these developments and they broke up the Assembly session on 28 November shouting at the Faulknerites ‘Traitors, Traitors, Out, Out’. On 6 December, DUP and VUPP members of the Assembly attacked the Faulknerites and the RUC had to be called to eject DUP and VUPP members from the Chamber. That evening, the DUP, VUPP and the West-Taylor Unionists united to form the United Ulster Unionist Council (UUUC) to bring down the Executive.

On 6 December the London-Dublin-Belfast Conference began at Sunningdale in England and lasted four days. A two-tier Council of Ireland and a fourteen-men Council of Ministers, seven from each side, was set up with unspecified executive powers, and a 60-member Consultative Assembly elected half by the Dáil and half by the Northern Assembly. The Council’s functions would be mainly in the field of economic and social cooperation. To make the RUC more acceptable to the nationalist minority in the Six Counties, the Council of Ministers was to be consulted on appointments to the Northern and Southern police authorities. In return for all this, the Dublin government agreed to accept the constitutional status of Northern Ireland, and to step up the offensive against the IRA, increasing the cooperation between the Gardai and RUC. It was clear that the Sunningdale agreement was designed to hold the Northern Ireland Executive together and increase repression of Republicans. It was in no sense designed to take steps to unite Ireland, but on the contrary, to make sure it remained divided.

The new Executive took office on 1 January 1974. Three days earlier, the SDLP had called for an end to the rent and rates strike against internment. The SDLP was ready and willing to play the role allotted to it by British imperialism. They were prepared to serve in government while internment continued and under the very man who introduced it – Brian Faulkner. And Austin Currie (SDLP) was responsible for one of the first acts of the Executive – legislation for deductions from benefit payments to people on rent and rates strike with a punitive 25p a week collection charge. The SDLP had supported and helped to organise the rent and rates strike. Now, as part of the Executive, they turned against the strikers.

As the Executive took office, Faulkner’s following was steadily disintegrating. On 4 January 1974 a motion rejecting the Sunningdale agreement was carried by a majority of 80 at the Ulster Unionist Council. Faulkner resigned as Unionist leader to be replaced by Harry West, but he remained head of the Assembly group – effectively a new party. Faulkner’s days were numbered and with them the whole power-sharing arrangement.

On 28 February there was a Westminster election. It had the effect of driving home what was already clear. The Protestant population and particularly the working class would not support power-sharing. The election result was a disaster for Faulkner. The United Ulster Unionist Council (UUUC) won 366,703 votes and eleven seats. The Faulknerites won none with 94,331 votes. The SDLP won one. The Labour Party won the election and Harold Wilson became Prime Minister, and Merlyn Rees Secretary of State for Northern Ireland.

On 23 April 1974 the UUUC held a conference at Portrush Co Antrim to work out an agreed policy. It was attended by representatives of the UDA and also by Enoch Powell – showing the support of a section of the British ruling class. The conference called for the scrapping of Sunningdale, the Executive and the 1973 Northern Ireland Constitution Act based on the White Paper 1973. It demanded a return of Stormont with full security powers and a new election.

The Ulster Workers Council Strike

After the collapse of the Loyalist Association of Workers (LAW) in 1973, a new body, the Ulster Workers Council (UWC) was set up by some LAW members. This new organisation concentrated on recruiting loyalist workers, in particular shop stewards and other key workers especially in the power stations. Loyalists had a firm grip on shop stewards and works committees in the power stations and throughout the engineering industry. LAW had been campaigning since 1971 to oust communists, Catholics and even Labour supporters from union positions in the industry.

On 14 May the Assembly was faced with a Loyalist motion opposing Sunningdale. The UWC announced if the motion was defeated they would call a general strike. The call was backed by the Ulster Army Council which coordinated Loyalist paramilitary organisations. The motion was defeated by 48 votes to 28 and that evening, the UWC strike began. Although intimidation was used by supporters of the UWC, the fundamental reason for the strike’s dramatic success was the mass support it had amongst the loyalist working class. The key weapon was control of the power stations and the UWC were able to reduce power output to a couple of hours a day. Industry was not able to operate and if workers turned up they were soon sent away. Shops and businesses closed down everywhere. UDA road blocks were set up all over Belfast and the RUC and British army made no attempt to intervene. By Monday 20 May the shut down was almost total.

On Friday 17 May car bombs exploded during the evening rush hour in Dublin and Monaghan in the Republic. There were no warnings given and 33 people were killed with over a hundred injured. The bombs were planted by the UVF. The UDA press officer, Sammy Smyth, said ‘I am very happy about the bombings in Dublin’.

On 19 May, Rees declared a state of emergency taking power to use troops to maintain essential services. But the troops did nothing where it mattered on the ground.

There were pathetic attempts made by the Irish Congress of Trade Unions on 21 May to lead workers back to work. One was a march led by Len Murray, TUC leader, which had less than 150 marchers – many not workers – who were attacked and jeered at by Loyalists and had to be protected by the British army throughout. The ICTU represented no-one but themselves.

The next day, the UWC banned petrol supplies to all but essential users – the latter being determined by the UWC. The economy was in chaos, the Executive was desperate.

The Provisional IRA set up emergency committees to distribute food, fuel and cash throughout the nationalist areas, ignoring the massive British army presence still being maintained in those areas.

On 23 May Faulkner, Fitt and Napier, the leader of the Alliance Party, flew to London and begged Wilson to use his troops. On 25 May Wilson went on television and in a vitriolic speech called the strike leaders thugs and bullies and referred to them as ‘people who spend their lives sponging on Westminster and British democracy . . .’. There was still no action.

The SDLP, having lost almost all credibility among the nationalist minority, threatened to resign by 27 May if Wilson did not use troops. On 27 May the troops moved in and occupied petrol stations throughout the Six Counties to supply essential workers like doctors and nurses. It was an empty gesture. The Loyalists threatened to close power stations down completely if troops went near, together with water and sewage plants.

The Faulknerites came to terms with reality. They called on Rees to negotiate with the UWC. He refused and they resigned on 28 May 1974, bringing the Executive down with them. The UWC called off its stoppage and the Assembly was suspended for four months and then indefinitely. That was the end of power-sharing.

A British army officer writing in the Monday Club magazine – Monday World – in Summer 1974 claimed that the Labour government had actually decided to use troops to end the stoppage on 24 May, but the Army refused. The writer said ‘For the first time, the Army decided that it was right and that it knew best and the politicians had better toe the line’. The Labour-imperialist government did toe the line just as the Liberal-imperialist government had done in March 1913 during the Curragh mutiny (see FRFI 9). Again, it was clear that real power lies outside parliament.

Power-sharing could only have worked if some improvement in the social position of the Catholic working class could be achieved. This was not possible in the context of the Six Counties – a sectarian statelet based on loyalist privilege and loyalist supremacy. The Loyalists understood that the Executive could only work if it offered something tangible to Catholic workers. And it was precisely their fear that it might which led them to bring it down.

The British state now recognised that there was no longer any other way than outright repression to defeat the real threat to its interests in Ireland – that from the nationalist masses led by their vanguard, the IRA.

David Reed

February 1982

to be continued

[Material from this article later went on to become part of Ireland: the key to the British revolution by David Reed]