Special Category – The IRA in English prisons, Volume 1 1968-1978, and Volume 2 1978-1985 by Ruan O’Donnell, Irish Academic Press, 2012 and 2015

From Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa to Bobby Sands, much has been written by and about Irish political prisoners, their sufferings at the hands of the British state and their steadfast resistance. In these two books, which are the first of what will be a four-volume set, Irish academic Ruan O’Donnell offers an original and valuable contribution to this body of research.

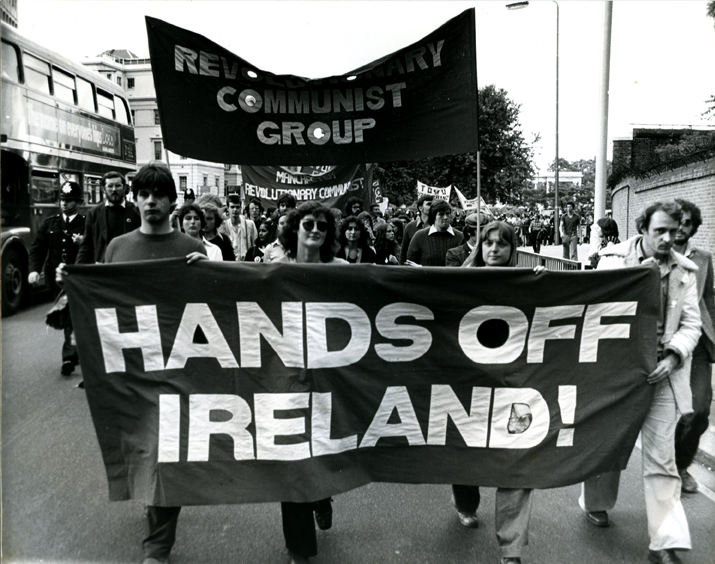

Special Category chronicles in detail the struggles of Irish Republican (and in particular IRA) prisoners held within prisons in England during the time known to the British media as ‘the Troubles’, to the British Army as ‘Operation Banner’ and to the IRA itself as ‘The Long War’. The books are based on material drawn from over 70 interviews with ex-prisoners, their relatives, lawyers and supporters, alongside copious documentation with which O’Donnell has been entrusted by the former prisoners – their letters, diaries, accounts and other documentation. There is also an extensive bibliography. Sources for Volume 2 include Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! (FRFI) and Hands Off Ireland! (HOI – published by the RCG from 1976 to 1979) and archives of correspondence between comrades then active in our organisation and Irish prisoners of war (POWs).

Although the focus is specifically on the Irish prisoners in England, of necessity these books also reflect the history of the wider Irish struggle during that period, and indeed the political movement in England as a whole, during a period which encompassed the Labour government of the 1970s, the rise of Thatcherism, the Malvinas/Falklands War and the Miners’ Strike.

The English prison system and the IRA

The story begins in 1968 at a time when ‘[t]he criminal justice system was undergoing an uneasy transition’ following the escape of Soviet spy George Blake from Wormwood Scrubs in 1966 (Vol 1, p5). Embarrassed by the Blake escape and by those of train-robbers Charlie Wilson and Ronnie Biggs, the government commissioned the Mountbatten Report, which recommended that all high security prisoners be concentrated in a single prison on the Isle of Wight. This recommendation was rejected and instead the British state adopted the ‘Dispersal System’ whereby high security prisoners were spread among six or seven different establishments; however Mountbatten’s other main recommendation on giving each prisoner a security classification from A to D, depending on perceived risk to the public, was implemented.

The overwhelming majority of IRA prisoners were designated Category A, the highest risk level, and therefore served their entire sentences within the Dispersal System. While on paper, their classification was no different to that of the most dangerous criminal prisoners and although ‘Special Category A’, which gives these books their title, never formally existed, it was abundantly clear from the outset to the prisoners, their families and their gaolers that Irish POWs were subject in practice to yet another level of scrutiny and repression.

The prisoners who entered the English system in the late 1960s and early 1970s faced an austere regime with few legal rights: their mail was censored, their visits were interfered with and they were subject to physical violence both from staff and, before they had stamped their mark on the system, from other prisoners. While until 1976 POWs held in the occupied north of Ireland were able to claim ‘political status’, in England this did not exist, meaning that from the point of entry to the system, prisoners faced immediate battles on issues such as prison uniform and prison work, both of which they refused as incompatible with political status. This led to protests and hunger strikes, which the authorities responded to with force-feeding:

‘Dolours Price was evidently the first IRA prisoner of the group to be force-fed in Brixton on 3 December 1973. A major scare came on the third day when she lost her breath and managed to pull the tube and feeding apparatus from her mouth. Marian Price was subject to her inaugural session on 5 December…This was her twenty-first day on strike and the distress and retching caused by the process was clearly audible in her sister’s cell’. (Vol 1, p142)

The prisoners strenuously resisted this vicious treatment. And, despite censorship and other barriers to communication, they knew they could count on there being tremendous support outside prison. Although obviously not altogether unhindered, prior to the Labour government’s introduction of the Prevention of Terrorism Act in November 1974, supporters of Irish liberation were able to organise far more openly than later became the case. O’Donnell describes how, following the death of Michael Gaughan on hunger strike in Parkhurst prison on 3 June 1974:

‘A large crowd of supporters assembled in Cricklewood… to march behind an eight-man Guard of Honour dressed in black pullovers and berets. From there the 3,000-strong procession continued on a two-hour march to Kilburn and into the Sacred Heart Church, Quex Road.’ (Vol 1, p202)

Stamping their mark on the system

These two volumes provide a densely packed, encyclopaedic history of the struggle of Irish political prisoners in English prisons. What comes over most strongly of all, alongside the brutality of the system, is their absolute determination and resilience. Aside from the few who were wrongly convicted and well known to be so, these were soldiers, for whom the same war against British rule which led them to take armed action on English or Welsh soil continued to be fought every minute they remained incarcerated: ‘Such men viewed imprisonment as “another stage of the war” in which “every day was a combat day when you could do something”’ (Interview with Eddie O’Neill, Vol 2, p295).

At the start the main focus of the prison struggle was for political status. Although this was never officially reinstated in the Six Counties, after the 1981 Long Kesh hunger strike it was restored in all but name, and at that stage, the main demand for those imprisoned in England became for repatriation to serve their sentences in Ireland. The books describe how this was accompanied by a constant fight to preserve human dignity within the prison setting, although it is made clear that any demands for better treatment and indeed for repatriation, remain part of the political campaign and are not simply pursued on humanitarian, grounds.

The books are full of accounts of blanket protests, sabotage and rooftop demonstrations. In carrying these out, partly through common cause and partly out of the necessity of survival, IRA prisoners politicised and worked together with English and other prisoners, both black and white. The influence of this relatively small group (no more than 100 at any one time) of Irish men and women, spread through the Dispersal System, changed the entire character of English high security prisons and the consciousness of those incarcerated in them for a period of 25 years.

A particular comradeship was established between Irish POWs and politicised black prisoners, and in telling this part of the history, O’Donnell is able to quote extensively from writings by Black Liberation Army prisoner Shujaa Moshesh in FRFI:

‘In prison I was meeting people who were giving me the Irish liberation view. The first thing I noticed was their commitment to the Irish struggle. They’re not halfway guys…Any kind of English hostility against black and Irish prisoners the screws will support because it’s in their interests to keep prisoners divided as well as matching their own racism. We had a lot of political discussion, were involved in protests and strikes. They proved the level of their commitment. It was a learning process; I’m sure I learned more from them than they learned from me. They used to ask me questions about aspects of the black struggle.’ (FRFI January 1989, quoted Vol 2, p67)

This unity between Irish and black prisoners informed all the major prison uprisings at Hull, Gartree, Wormwood Scrubs, Albany and Parkhurst which are detailed in O’Donnell’s books. The Irish prisoners also gained support for their actions from swathes of the English ‘gangster’ prison population who, whatever their pre-prison views on the Irish conflict, gave the IRA men respect for their dedication – and of course were forced to recognise that if they did not work with the POWs they would have to face the consequences.

Solidarity

These books are refreshingly partisan about the major conflict being described, ie firmly on the side of the Irish liberation fighters and completely against the role played by their British imperialist captors. There is no pretence at any ‘lack of bias’ on that score. Having established this as a given throughout the account, the books then take, insofar as possible, an even-handed approach to any disputes and differences which occurred within the movement itself, either inside or outside of prison.

All those who are seen to have contributed to solidarity with the prisoners, be it the Troops Out Movement, the Prisoners’ Aid Committee, the nun Sister Sarah Clarke, the Young Liberals or the Irish Freedom Movement – which was set up at a similar time to the Irish Solidarity Movement (ISM) in which the RCG played a pivotal role – are given their due. There is no sectarianism here and condemnation is reserved for those who truly merit it – vicious politicians such as Labour Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Roy Mason (Vol 1, pp402-3), and Britain’s then biggest ‘left’ organisation, the Communist Party of Great Britain, which had a disgraceful stance in relation to the struggle in Ireland:

‘…the CPGB refused to be drawn into a declaration of solidarity. [It] remained wedded to a de facto policy of following the lead of communist affiliates in the North of Ireland, a body with disproportionate input from persons drawn from the Unionist, as well as sectarian Loyalist community. This produced a glaring paradox whereby the CPGB voiced support for international leftist revolutionary organisations in Continental Europe, Africa and Asia, while condemning the closest equivalent within the UK and Ireland.’ (Vol 2, p27)

Working class unity

Although completely absent from the narrative of Volume 1, the RCG is cited frequently throughout Volume 2, and clearly shown to have played a central role in prisoner solidarity, both through our dedicated organising of events such as demonstrations outside prisons, the Home Office etc, and because of our comrades’ consistent political correspondence and dialogue with the prisoners, which allowed FRFI and HOI to be the first to publicise many of the attacks on prisoners or acts of resistance by them.

Volume 2 of Special Category covers in some detail the setting up of the ISM under the heading ‘A new Broad Front’:

‘On 13 April 1983 IRA prisoners in Albany endorsed a complicated process of realignment taking place within Britain’s numerous pro-Republican groupings. The impetus derived from the 20 November 1982 conference… organised by the North London Irish Solidarity Committee. The stated aim, as outlined by David Yaffe (aka Reed) of the Revolutionary Communist Group, was the formation of a national Irish Solidarity Movement by means of achieving a “real unity – based on the common interests of the Irish people and the British working class in the defeat of British imperialism”… Alastair Logan, Helen O’Brien and Michael Holden provided information and analysis on the prisoner dimension…and ensured an Irish republican input from the outset.’ (Vol 2, pp285-6)

O’Donnell goes on to describe in detail the setting up of the ISM, the forces it drew in and the inspiring events it organised, up to 1984, when the very same weekend that the IRA spectacularly bombed the Tory Party conference hotel in Brighton, recently freed POW John McCluskey shook the hand of striking Kent miners’ leader Malcolm Pitt on the platform at an ISM rally in London (p385).

Photo by Paul Mattson

Volume 2 ends in 1985, at the point when Sinn Fein has begun to operate as an electoral party and looks forward to the ‘end game’ of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement (p393).

These books have already sold well and been widely praised. They will clearly go on to become one of the definitive accounts of this aspect and period of the struggle for Irish freedom.

Nicki Jameson

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! 249 February/March 2016