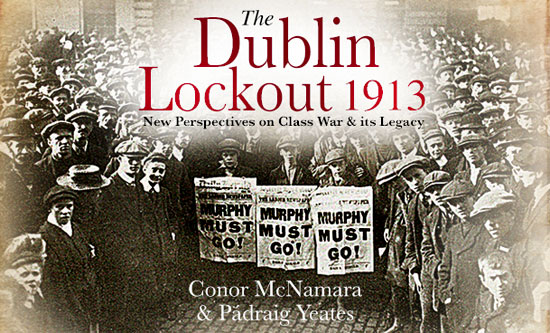

The Dublin Lockout 1913 – New Perspectives on Class War and its Legacy – Conor McNamara and Padraig Yeates, Irish Academic Press, 2017, €24.99/€49.99

Much has already been written about the 1913 Dublin Lockout but this collection – published in 2017 and comprised of essays written up from a centenary commemoration event – contains some interesting insights.

The book starts with a handy chronology of the relevant events of 1913-14, beginning on 19 July 1913, when William Martin Murphy, the President of the Dublin Chamber of Commerce, called his workers to a midnight meeting to tell them that anyone belonging to the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) will be sacked.

Among all the other aspects of the subsequently unfolding drama of sackings, strikes and lockout, the chronology details how the English TUC initially promised solidarity but then rapidly sold out the Irish workers, to the anger of ITGWU leader James Larkin, who, on 10 October 1913, was ‘a guest of honour at a rally…where he [told] the audience that British trade union leaders were “about as useful as mummies in a museum” because they refused to sanction sympathetic strikes in Britain.’

Having established this background, the collection moves on to examine aspects of the Lockout which have not been the main thrust of previous writings. One chapter looks at events from the perspective of Irish Americans, another in the appropriately named ‘Tale of Two Cities’ compares Dublin and Belfast at the time of the Lockout, while yet another chapter focuses on the life of revolutionary Irish republican, women’s rights activist, trade unionist and pro-Soviet socialist Helena Molony, who played an active role both in the Lockout and in the 1916 Rising.

Another of the smaller and specifically focussed essays is entitled ‘Quick Witted Urchins – Dublin’s Newsboys in Challenging Times, 1900-1922’. In a time before not only today’s modern communication methods, but also without TV or radio, the newspaper was king. Daily newspapers would sometimes produce several editions per day and the newsboys – who were employed directly by the papers themselves, as opposed to by distribution outlets or shops – were essential to getting them out to the buying public. Publications represented every shade of political opinion, and the ITGWU had its own paper, the Irish Worker. As the book records: ‘by organising the newsboys, Larkin also ensured that his own newspaper had an effective distribution network’.

The newsboys were young, precarious workers, from impoverished working class families. In addition to being the objects of both derision and charity, they were workers in their own right, as well as being integral to the communication of political developments via the news media. Despite, such workers, like today’s delivery drivers and couriers, being hard to organise, the newsboys had staged their own strike in 1911, and in 1913, the book records:

‘In popular memory, the Lockout began with a symbolic act of defiance, when tramway drivers walked away from their trams and pinned the famous red hand badge to their uniforms. In reality the first blow was actually delivered over a week previously by William Martin Murphy; on 15 August, Murphy removed forty men and twenty boys from the despatch delivery office of the Irish Independent… there was an almost immediate response to this from the workers who placed pickets on the office, and that afternoon the newsboys refused to sell the Independent’s sister publication the Evening Herald.’

The commentary in parts of this collection, such as ‘1913: The Cinderella Centenary’ by Padraig Yates, reflects the revisionist politics of the Workers Party, to which the author of that chapter and joint editor of the collection belongs, and this can strike a discordant tone at times. However, even these chapters contain some useful ‘myth-busting’, such as the description (p172) of how the genuine contribution of ITGWU/Irish Women Workers’ Union leading militant Rosie Hackett to the events of 1913 was unnecessarily exaggerated and embroidered by some of those who successfully campaigned on the centenary for a Dublin bridge to be named in her honour.

Further, this slant is not overwhelmingly present in every chapter, with the book’s contributors taking a range of political stances, with the oral history project, ‘The legacy of the Lockout’, which is reported on in chapter 11, having been compiled by reporters with an even wider range of opinion.

This is a collection which is certainly worth dipping into for anyone interested in the working class history of Ireland.

Nicki Jameson

For a history and analysis of the events and politics of the Dublin Lockout, go to http://www.revolutionarycommunist.org/europe/ireland/3105-td080813