Lecture 8: The transformation of money into capital

The background to the development of capital is the circulation of commodities, in particular the more developed form of circulation or commerce. The modern history of capital dates from the creation in the 16th century of world commerce and a world market.

Money, the final product of the circulation of commodities, is the first form in which capital appears – in the form of monetary wealth, as the capital of the merchant and the usurer.

The first distinction to note between money as money and money as capital is the difference in their form of circulation. In C-M-C, the simplest form of the circulation of commodities, the transformation of commodities into money, and the change of money back into commodities, is selling in order to buy. Money here is always moving further away from its starting point. However alongside this form there is a different form M-C-M, the transformation of money into commodities and the change of commodities back again into money, or buying in order to sell. Here money returns back to the same hand. Money which circulates in this way is transformed into capital.

Let us examine this movement more closely. C-M-C, the conversion of a commodity from one which is a non use-value to the owner to one which is a use-value, is perfectly rational. Linen, for example, is exchanged for the bible. However the movement M-C-M would be absurd if the intention was to exchange by such means two equal sums of money. This movement does not make sense unless there is a quantitative difference between the money thrown into circulation and that taken out at the end. The exact form of this process is, therefore, M-C-M’ where M’= M + M, the original sum advanced plus an increment. This increment or the excess over the original value is the ‘surplus-value’. ‘The value originally advanced…not only remains intact while in circulation, but adds to itself a surplus value or expands itself. It is this movement which converts it into capital.’ (p150)

The simple circulation of commodities C-M-C or selling in order to buy, is a means of carrying out a purpose unconnected with circulation, that is consumption or the satisfaction of definite wants. It is limited by this aim or object. On the other hand M-C-M, buying in order to sell, begins and ends with the same thing, namely money. This fact makes the movement an endless one. Therefore, the circulation of money as capital is an end in itself for the expansion of value takes place with a constantly renewed movement. The circulation of capital has no limits. (p151)

As the conscious representative of this movement, the possessor of money becomes a capitalist. ‘His person, or rather his pocket, is the point from which the money starts and to which it returns.’ (p152) The expansion of value becomes the capitalist’s subjective aim. Only in so far as the appropriation of ever more wealth in the abstract becomes the sole motive of his operations does he function as a capitalist, ‘as capital personified and endowed with consciousness and will.’ (p152) Use-values must never be seen as the real aim of the capitalist, nor the profit of a single transaction but ‘restless never-ending process of profit-making’. As Marx says the miser is merely a capitalist gone mad while the capitalist is a rational miser. The never-ending argumentation of money which the miser strives after by withdrawing his money from circulation, the capitalist attains by constantly throwing it afresh into circulation. (p153)

Value now becomes value in process, money in process and as such, capital. It comes out of circulation, enters it again, preserves and multiplies itself in circulation, emerging from it in an increased amount, and begins the cycle again and again. M-M’, money which begets money, is the description of capital given by its first interpreters the Mercantilists. Buying in order to sell dearer M-C-M’ is a form of capital which seems peculiar to one kind of capital alone, merchants capital. However industrial capital is money that has been changed into commodities, and reconverted into more money through the sale of these commodities. Here Marx says that events which take place outside the sphere of circulation, in the interval between buying and selling, do not affect the form of this movement. A point which becomes clear later. Finally in the case of interest bearing capital, the circulation is presented in abridged form M-M’, in its final result without an intermediate stage. M-C-M’ is therefore the general formula for capital as it appears unmediated in the sphere of circulation.

Contradictions in the general formula for capital

The formula for capital M-C-M’ contradicts all the previously developed laws relating to the nature of commodities, value and money and even circulation itself. Why should the inverted order of the circulation of commodities change its character. Especially as it is an inverted order which has no bearing on two of the three persons who transact business. (As a capitalist, I buy commodities from A and sell them to B). This inversion does not take us outside the sphere of circulation and so we must go on to examine whether there is anything in simple circulation permitting an expansion of the value that enters circulation.

In so far as the circulation of commodities effects a change in the form alone of their values it must be the exchange of equivalents. It is only through a mixing up of use-value and value that vulgar economy attempts to show simple circulation as a source of surplus value. Marx gives a passage from Condillac which demonstrates this confusion (p159-60).

Marx considers the case of a seller who is able to sell his commodities above their value say £100 worth for £110, a nominal price rise of 10 per cent. He then becomes a buyer and confronts a third owner of commodities who also wants to sell his commodities 10 per cent above their value. The net result is the same as if the commodities were sold at their value. The same arguments hold if commodities are sold below their value.

The creation of surplus value or the conversion of money into capital cannot be explained by the argument that commodities are sold at above or below their value.

Another argument to sustain the delusion that surplus-value arises from a nominal increase of prices or the ability of the seller to sell commodities above their value requires a class which buys but does not sell, that is consumes but does not produce. The existence of such a class is inexplicable from the standpoint of simple circulation. The money which such a class has must constantly flow into their pockets without exchange ‘by might or right’ from the pockets of the commodity owners themselves. To sell commodities above their value to such a class is to take back part again of the money that was previously given to it. A footnote here cites a Ricardian attack on Malthus for arguing this kind of absurdity. (p162) This is no way of getting rich or producing surplus value.

Marx considers the sale of commodities above their value to buyers who cannot retaliate. A sells wine worth £40 to B and obtains from him corn to the value of £50. A has converted his £40 to £50, has made more money out of less. In this case the value in circulation has not changed only its distribution. £90 is distributed differently between A and B. ‘Circulation or the exchange of commodities, begets no value.’ (p163)

Here Marx explains why in analysing the standard form of capital, as it determines the economic organisation of modern society, the well known forms of merchant’s capital and money lenders capital were left out of account. If the transformation of the merchant’s money into capital is to be explained other than by the producers being cheated then a long series of intermediate steps would be necessary which, as yet, with the simple circulation of commodities our only assumption, are entirely absent. Merchant’s capital and interest-bearing capital are derivative forms of the standard form of capital even though they appeared earlier historically. This can only be explained at a later stage in Volume III of Capital.

The conversion of money into capital has to be explained on the basis of the exchange of equivalents. The embryonic capitalist must buy commodities at their value, must sell them at their value and at the end of the process withdraw more money from circulation than was put into it at the beginning. This development must take place both within circulation and outside of it – an apparent contradiction. These then are the conditions of the problem. Hic Rhodus, hic salta! (Rhodes is here. Leap here and now.)

The buying and selling of labour-power

As circulation cannot explain the increase in value then the change must be sort in one of the terms in the formula for capital M-C-M’. It cannot take place in the money itself for this is hard cash which does no more than realise the value of the commodity it is buys or pays for. Nor can it originate in the second act of circulation, the resale of the commodity, which does no more than transform the article from its bodily form back into its money form. The change must take place in the commodity bought by the first act M-C. But not in its value for equivalents are exchanged and the commodity is paid for at its full value. So we are forced to the conclusion that it must lie in the use-value of the commodity bought in the first act of exchange, that is in its consumption. (p167)

The possessor of money, our embryonic capitalist, must find in the market a commodity whose use-value possesses the peculiar property of being a source of value, whose actual consumption is therefore itself an objectification of labour and consequently a creation of value. Such a commodity does exist: the capacity for labour or labour power.

By labour power or labour capacity is meant the aggregate of those mental and physical capabilities existing in a human being which he exercises in producing a use-value of any description.

Certain conditions are necessary for this to be possible:

- The first condition is that the person must be the free owner of his labour power, in order that he/she may sell it. It must be sold for a limited period of time for if it were sold once and for all, the person would selling him/herself, would be converted from a free person into a slave, from the owner of a commodity into a commodity.

- The second is that the owner of the commodity labour-power has no other commodities for sale; is short of everything necessary for the realisation of his/her own labour power.

Such conditions have no mere natural basis, neither is their social basis one that is common to all historical periods. They are the outcome of historical development. So too are the economic categories being discussed the outcome of an historical process.

‘The appearance of products as commodities presupposes such a development of the social division of labour, that the separation of use value from exchange value, a separation which first begins with barter, must have already have been completed. But such a degree of development is common to many forms of society…On the other hand, if we consider money, its existence implies a definite stage in the exchange of commodities…’

Different functions of money point to very different stages in the process of social production.

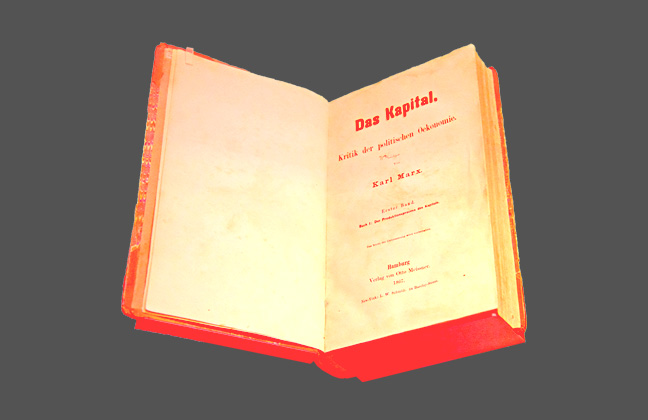

‘…with capital. The historical conditions for its existence are by no means given with the mere circulation of money and commodities. It can spring into life, only when the owner of the means of production and subsistence meets in the market with the free labourer selling his labour-power. And this one historical pre-condition comprises a world’s history. Capital, therefore, announces from its first appearance a new epoch in the process of social production.’ (p170)

Labour-power has a value which like all other commodities is determined by the labour-time necessary for the production and consequently the reproduction of this specific commodity. This is the cost of the upkeep of the labourer. This resolves itself into the cost of the labourer’s necessary means of subsistence, to maintain the labourer in a normal state as a labouring individual. This includes food, clothing, fuel, and housing etc varying according to the climatic and other physical conditions of the country. Other necessary wants are a product of historical development and the degree of civilisation of the country etc. So a historical and moral element enters into the value of labour- power.

As the owner of labour-power is mortal the upkeep of labour power includes the maintenance of the labourer and his/her physical reproduction. This includes the labourer’s family and his/her children. The expenses of education and training of labour-power (excessively small in the case of ordinary labour-power) enter in the total value spent in its production.

The value of labour-power resolves itself into the value of a definite quantity of the means of subsistence. It therefore varies with the value of these means or with the quantity of labour necessary for their production. The minimum limit of the value of labour-power is the value of the means of subsistence physically indispensable for the labourer to renew his capacity to labour on a daily basis.

When labour power is sold its use-value does not immediately pass into the possession of the buyer. Its value is fixed before sale by the labour-time spent on its production but its use-value is its own subsequent consumption or expenditure of labour-power. In all capitalist countries the use-value of labour-power is advanced to the capitalist before it is paid for. It is consumed for a period of time before being paid for.

The consumption of labour-power is at one and the same time the production of commodities and surplus-value. The consumption of labour-power is completed like any other commodity outside the limits of the market or of the sphere of circulation.

We now desert this sphere within whose boundaries the buying and selling of labour power goes on and in which alone rule Freedom, Equality, Property and Bentham. Freedom, because each acts according to his own ‘free will’; Equality, because they meet each other ‘equally’ as commodity owners and exchange ‘equivalent for equivalent’; Property because each disposes of what is only his own; and Bentham because each looks only to himself. Everything is done in accordance with the pre-established divine harmony of things, to further their mutual gain and advance the ‘common weal’ and the interest of all.

Marx says in leaving this sphere which furnishes the ‘Free-trader Vulgaris’ with his views and ideas we can now perceive a change in the physiognomy of our dramatis personae. ‘He who was before the money owner, now strides in front as capitalist: the possessor of labour-power follows as his labourer. the one with an air of importance, smirking, intent on business; the other, timid and holding back, like one who is bringing his own hide to market and has nothing to expect but – a hiding’.(p176)

We now move into the hidden abode of production where we shall see not only how capital produces, but how capital is produced. We shall at last understand the secret of profit making.