Lecture 4: Tracing the origin of money form of value

‘Money is the root of all evil’, according to a popular expression. And given the overbearing influence of money in our lives it is not surprising that many utopian socialists have argued for the abolition of money or the abolition of banks as a way of ridding us of the evils of the capitalist system. Yet others have argued that the capitalist system doesn’t even need money anymore and modern computer technology will so away with it. But capitalism without money is not possible and would be equivalent, as Marx once commented, to Catholicism without the Pope.

To summarise the argument so far. Marx began his analysis in Capital with the commodity and examined exchange-value, or the exchange relation of commodity to commodity, in order to get at the value that lies hidden behind it. He showed that the value of commodities has a purely social reality and that they acquire this reality insofar as they are expressions or embodiments of one identical social substance, that is, abstract human labour. Further exchange-value is the only form in which the value of commodities can be expressed. The value of commodity can only manifest itself in the social relation of commodity to commodity.

‘In fact, we started from exchange-value, or the exchange relation of commodities, in order to get at the value that lies hidden behind it. We must now return to this form under which value first appeared to us.’ (p47)

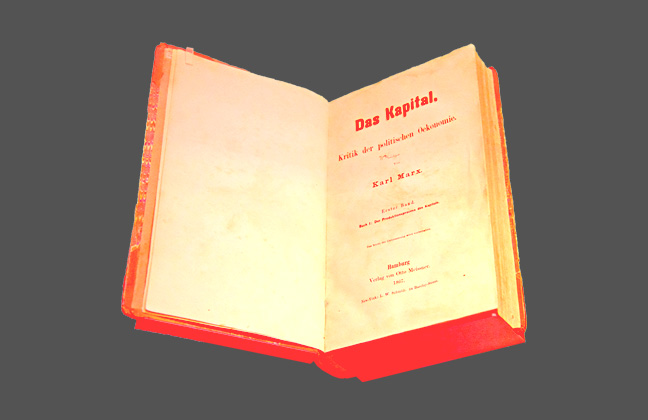

Commodities clearly have a value-form common to them all. This contrasts with the varied bodily form of their use-values. We refer to their money-form. Marx sets himself the task of tracing the genesis of this money-form, ‘of developing the expression of value implied in the value-relation of commodities, from its simplest almost imperceptible outline, to the dazzling money-form.’ To ‘solve the riddle presented by money.’ (p48)

The creation of money, as we shall see, proceeds logically and historically from the contradiction between the particular nature of the commodity as a use-value and its general nature as a value.

To show this Marx begins with the simplest exchange relation-that between two different commodities. This gives us the simplest value expression, the elementary or accidental form of value. It relates to an underdeveloped form of commodity production.

Elementary or accidental form of value

20 yards of linen = 1 coat

Marx goes on to examine the two poles of the expression of value – opposite extremities of the value-form: relative and equivalent form of value. The whole mystery of the form of value lies hidden in this elementary form.

In the value expression 20 yards of linen = 1 coat, the linen expresses its value in the coat. The value of the linen is represented as a relative value, appears in relative form, the coat officiates as equivalent, or appears in equivalent form. The value of the linen is expressed only relatively, that is, by the bodily form of the commodity coat, the value of one by the use – value of the other.

Marx calls the relative and equivalent forms of value mutually dependent and inseparable elements of the expression of value which are at the same time mutually exclusive and antagonistic extremes – that is, poles of the same expression.

It is not possible to express the value of the linen in linen. 20 yards of linen = 20 yards of linen is no expression of value. The relative form of value presupposes the presence of some other commodity under the form of an equivalent. On the other hand the commodity which serves as equivalent cannot at the same time assume a relative form. We can reverse the equation to 1 coat = 20 yards of linen and then the value of the coat is expressed in relative form and the linen acts as equivalent. But a single commodity cannot assume, in the same expression of value, both forms. The very polarity of these forms makes them mutually exclusive.

Which is relative and which is equivalent is purely accidental – relative to the under developed form of commodity production.

Relative form of value

In order to understand the relative form of value we have to consider it independently of its quantitative aspect. We must remember that the magnitudes of different things can only be compared quantitatively if they are expressed in the same units – ie they are commensurable. Whether the linen is equal to one or many coats necessarily implies some common quality that constitutes that equality: linen equals coat. That is as magnitudes of value linen and coats are expressions of the same units. Marx borrows an illustration from chemistry: propylformate and butyric acid are both composed of the same chemical formula CHO. If we should equate propylformate to butyric acid, we should therefore refer to their common chemical base (Carbon, Hydrogen and Oxygen – these substances are combined together in the same proportions in each case) and ignore their physical differences.

The linen and the coat, whose identity of equality is assumed, however, do not play the same part. It is only the value of the linen that is expressed and that by reference to the coat as its equivalent, as something it can be exchanged for. The linen’s own value receives independent expression, for it is only as value that it is comparable with the coat as a thing of equal value, is exchangeable for the coat.

‘If we say that, as values, commodities are mere congelations (congealed quantities) of human labour, we reduce them by our analysis, it is true, to the abstraction, value; but we ascribe to this value no form apart from their bodily form (materialised in a particular use-value). It is otherwise in the value-relation of one commodity to another. Here, the one stands forth in its character of value by reason of its relation to the other’. (p50)

By making the coat equivalent to the linen, we equate the labour embodied in the former to that in the latter. And the different kinds of concrete labour to their common character as abstract human labour.

But something more is needed. Human labour power in motion, or human labour creates value, but is not itself value. It becomes value in is congealed state when it is embodied in some object. In order to express the value of the linen, the value must be expressed as having an objective existence, must be perceived as being something materially different from the linen itself, yet something common to the linen and all other commodities.

As the equivalent in the relation we have discussed, the coat counts qualitatively as the equal of the linen, something of the same kind, because it is value. It is a thing in which value is manifested, or which represents value in its tangible bodily form. Yet the coat is a mere use-value, which no more expresses value than does the first piece of linen we take hold of. This shows that when placed in value-relation to the linen, in the position of equivalent, the coat signifies more than when out of that position. It exists as embodied value, ‘as a body that is value’.

Marx gives an analogy to show the importance of the relation. A cannot be your majesty to B, unless in B’s eyes ‘your majesty’ assumes the bodily form of A, and what is more, with every new father of the people, changes its features, hair and many other things besides. (p51-2)

If we return to the linen and coat: the value of the commodity linen is expressed by the bodily form of the commodity coat, the value of one by the use-value of the other. So the linen acquires a value-form different from its physical form. The value of the linen thus expressed in the use-value of the coat has taken the form of relative value.

We now turn to the quantitative determination of relative value. The value form must not only express value generally but also value in a definite quantity. 20 yards of linen = 1 coat implies that the same quantity of the value substance (congealed labour) is contained in both; that the quantities in which the two commodities are present contain the same amount of labour, or the same quantity of labour-time. But the labour-time necessary for the production of 20 yards of linen or one coat changes with the productivity of the labour of weaving or tailoring.

1. The value of linen varies, coat remains the same.

(a) Labour-time necessary for the production of linen doubles due to exhaustion of flax growing soil – value of linen also doubles. So 20 yards of linen = 2 coats.

(b) Labour-time necessary for the production of linen halves as a consequence of improved looms. So 20 yards of linen = one-half a coat. The relative value of commodity A (linen) rises or falls directly as the value of A, the value of B (coat) supposed constant.

2. value of linen remains constant, value of the coat varies.

(a) Labour-time necessary for the production of the coat doubles. So 20 yards of linen = one-half a coat.

(b) If the value of the coat falls by one half then 20 yards of linen = 2 coats. Hence if the value of commodity A remains constant, its relative value rises and falls inversely with the value of B.

3. value of linen and coat both change in the same direction and in the same proportion. In this case 20 yards of linen = 1coat however much their values may alter.

4. value of linen and coats both vary but differently in the same or opposite directions. Then the changes in the relative value of A may be deduced from the results of 1, 2 and 3.

Marx concludes that real changes in the magnitude of value are neither unequivocally nor exhaustively reflected in their relative expression, that is, in the equation expressing relative value.

The equivalent form of value

When the linen expresses its value by the coat’s bodily form – use-value – it gives the coat the special character of equivalent. When we say that a commodity is in equivalent form we express the fact that it is directly exchangeable for other commodities. However when a coat becomes the equivalent form of linen, and is thus directly exchangeable with linen we are far from knowing in what proportion the two are exchangeable. The value of the linen being given the proportion will depend on the value of the coat. And the value of the coat is determined independent of its value-form by the socially necessary labour-time for its production. The commodity serving as equivalent can never express its own value. When a commodity acts as equivalent, it is only the equivalent for another commodity, and its own value is not quantitatively expressed.

Marx then points out a number of features of the equivalent form of value.

- The first peculiarity in the equivalent form of value is this: that use-value becomes the form of manifestation, the phenomenal form of its opposite, value. The bodily form becomes a value-form only when some other commodity enters into relation to it. Marx gives the analogy of weight through the example of the sugarloaf and various pieces of iron, whose weight has been determined beforehand. The iron, as iron, is no more the form of manifestation of weigh tthan the sugar loaf. Nevertheless in order to express the sugarloaf as so much weight, we put it in a weight relation with the iron. In this relation the iron stands for embodied weight, a form of manifestation of weight. A certain quantity of iron serves as the measure of the weight of the sugarloaf. Just as in its relation to the sugar loaf in the scales the material body (the mass of iron) represents weight only, so the bodily form of the coat, in its value relation with the linen, represents value only.

But here the analogy ceases. While weight is a natural property, the value-relation is a non-natural social relation.

2. The coat as equivalent form is an embodiment of society’s labour, or of abstract human labour; and at the same time it is the product of some specifically useful concrete labour ie tailoring. So the second peculiarity is that concrete labour becomes the form under which its opposite, abstract labour, manifests itself.

3. Because this concrete labour, tailoring in our case, is directly identified with undifferentiated human labour, or abstract labour, it also passes as identical to any other sort of labour. Therefore while it is labour of private individuals, yet, at the same time, it ranks as labour directly social in character. This leads to the third peculiarity of the equivalent form: the labour of the private individual takes the form of its opposite, labour directly social in form. (p58-9)

At this points Marx shows how Aristotle was limited in his understanding of value-form and was prevented from seeing the labour basis of the qualitative equality in commodities because of the society he lived in and the social conditions of his time. This was because Greek society was founded on slavery and had for its natural basis the inequality of human beings and their labour powers. The idea of human equality could not take root in such a society. This would only be possible when the great mass of products of labour took the form of commodities.

With the elementary form of value we see that the value of a commodity obtains independent and definite expression by taking the form of exchange-value. At the beginning of Chapter 1 when Marx said, ‘in common parlance’, that the commodity is a use-value and exchange-value he was strictly speaking wrong. The commodity is a use-value and a value. It manifests itself as this two-fold thing as soon as its value assumes independent form ie the form of exchange-value. It never assumes this form when isolated but only in relation to another commodity. Once we know this then using the ‘common parlance’ does no harm, it simply serves as an abbreviation. Marx then sums up the results of the analysis so far:

‘Our analysis has shown, that the form or expression of the value of the commodity originates in the nature of value, and not that value and its magnitude originate in their mode of expression as exchange-value’. (p60)

Marx ends this section on the Elementary form of value by saying that the elementary value-form is also the primitive form under which a product of labour appears as a commodity. The development of this value-form coincides with the transformation of the generality of labour products into commodities. The elementary value form is an embryonic form which undergoes a series of metamorphoses before it can ripen into the price-form.