FRFI 214 April / May 2010

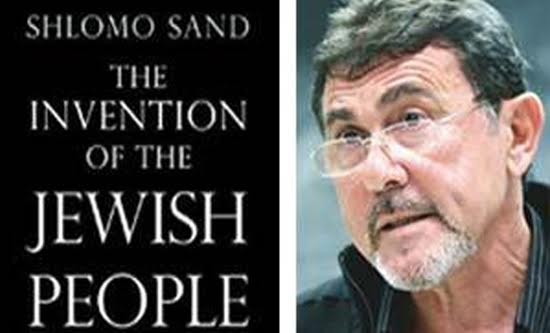

The invention of the Jewish people, Shlomo Sand, translated from the Hebrew by Yael Lotan, Verso 2009, 332pp, £18.99. ISBN 978-1-84467-422-0

‘I could not have gone on living in Israel without writing this book. I don’t think books can change the world – but when the world begins to change, it searches for different books’

Shlomo Sand, 2008

The world is indeed changing. Since the recognition of an Israeli state by the United Nations in 1947 and the extension of its borders in 1967 by war and occupation, Zionism* has demanded and received unconditional support from the US and Europe and silence on its record of oppression of the Palestinian people. Today this collusion is breaking down and the Zionist state of Israel can no longer claim that the exceptional tragedy of the European Holocaust puts it beyond reason and responsibility for its actions. Israel is being ever more exposed as a racist, apartheid state with a record of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Politics and archaeology

At the heart of this excellent book is the thesis that there is no such thing as ‘the Jewish people’. Sand comprehensively unpicks the dominant Zionist narrative, what he calls the ‘mythistory’, by reviewing a mass of historical research, including archaeological finds that were buried, neglected or banished by the Zionists. He describes how in the 1950s and 1960s Zionist archaeologists deliberately configured excavations and discoveries to match the heritage story of the Old Testament. So, for example, Moshe Dayan, Israeli Chief of Staff, minister of defence and amateur archaeologist, collected ancient artefacts, ‘some of them stolen’, and systematically destroyed ‘ancient mosques, even from the eleventh century’, in order to construct a past that matched the biblical text (p113). With carefully referenced evidence, Sand contends that these Zionist investigators knew that the celebrated biblical kingdoms of David and Solomon were relatively small settlements inflated by the foundation myths of the early historical period. Most significantly, he says there is no substantial evidence of a forced exile by the Romans of Jewish people in the first century after the fall of the Second Temple. On the contrary, all investigation supports the view that the majority of the population remained in Judea and Canaan as a conquered people, and lived on through the centuries as peasant farmers. They were converted, willingly or otherwise, to add to the growing numbers of Christians and Muslims, under the powers of the Byzantine and Caliphate Empires.

Khazars and Judaism

The Jewish religion also continued to grow and spread, particularly in the area between the Black Sea and the Caucasus mountains then known as Khazaria. Judaism was as active and as proselytising a religion as the other two monotheisms, converting many kings and tribal chiefs who in turn imposed their chosen religion on their subjects. Furthermore, a range of different ethnicities and peoples embraced and adapted the Jewish religion into a variety of sects. Records indicate the existence from the fifth century of a great Khazar Empire on the steppes of Asia, ruled by Jewish monarchs who conquered, enslaved and expanded their domain for hundreds of years. The torrential Mongolian invasion led by Genghis Khan in the early thirteenth century swept aside the Khazar kingdom, along with neighbouring societies. This invasion from the east depopulated the steppe lands which perished with the destruction of the ancient irrigation systems that had supported agrarian food cultivation and settlements. A small Khazar community was all that remained and it survives today in the foothills of the mountains of the Caucasus. Khazarians retreated into the western Ukraine, Polish and Lithuanian territories. There, they formed the majority of what came to be known as Ashkenazi Jews, and settled in eastern Europe as a population quite dislocated from the Semitic tribes of the Old Testament.

Arthur Koestler versus Zionist mythistory

The history Sand introduces to the reader is neither original nor new, but one that is authenticated by a historical record that has been deliberately buried. Arthur Koestler, born in Hungary in 1905, was a close supporter of the Zionist right-wing leader Vladimir Jabotinsky in his youth. He joined the Communist Party in Berlin in 1931 and worked undercover for the Comintern in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. He resigned from the Communist Party in 1938 in disgust with Stalin. His popular anti-communist book, Darkness at Noon, was published in 1940 to great acclaim. In 1976 Koestler published The Thirteenth Tribe: the Khazar Empire and its heritage, drawing on the earlier research and collecting together the evidence for the Khazar Empire. Koestler’s study concludes that:

‘The large majority of surviving Jews in the world is in eastern Europe – and thus mainly of Khazar origin. If so, this would mean that their ancestors came not from the Jordan but from the Volga, not from Canaan but from the Caucasus, once believed to be the cradle of the Aryan race; and that genetically they are more closely related to the Hun, Uigur and Magyar tribes than to the seed of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.’ (cited p239)

The Thirteenth Tribe is focused on the origins of the Ashkenazi, or European, Jews and does not extend to the history of the Sephardic Jewish communities of Spain and Portugal or the Judaised people of Ethiopia and North Africa. Koestler was puzzled by the hostile reception to his book because he remained a Zionist and supported the State of Israel, which he regarded as ‘based on international law’ and not on ‘the hypothetical origins of the Jewish people, nor on the mythological covenant of Abraham with God’ (p239). When the book appeared, Israel’s ambassador to Britain described it as ‘an anti-Semitic action financed by the Palestinians’ (p240)

Historiography

Sand’s book has much to offer, even to those uninterested in Old Testament stories or who are past caring whether the displacement of the Palestinians is carried out by Zionists of Semitic or other tribal origins. It is a book about history and historical truth in general and readers will find their critical faculties sharpened and understanding deepened by this study. History down the ages informs us not just about the past but also about the historian. Sand says, quoting the Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce that ‘any history is first of all a product of the time of its writing’. Historians, as people, as scholars, as professionals, as members of educational establishments or as record keepers, present their work from a contemporary and ideological standpoint. This evaluation of history is known as ‘historiography’ and leads to close examination of the sources, theories, methods of research and writing of historians. Sand subjects the ‘Zionist historiography of the Jewish past’ (p19), to a rigorous examination of the values it promotes and the truths that it ignores or buries.

The rise of the nation state

Departments of Jewish History in Israel and universities around the world promote an ethno-national history of Judaism that derives from 19th century Zionism. This was the period when other ‘nationalisms’ arose as expressions of the needs of capitalism or ‘modern industrial societies’ as Sand says (p36). In an interesting review of the rise of modern nationalism, Sand describes the emergence of new nations from the collapsing empires and disintegrating peasant communities as coming from above. Ruling powers employed deliberate, ideological practices, rituals and ceremonies designed to foster an inclusive national identity. Historians justified the new power elites by writing, or re-writing, histories of a national past, reviving and inventing distant figures to serve the present need.

Modern nationalisms, however, are characterised by their inclusiveness. It was their purpose, as it largely remains today, to create a national territory in which all citizens are members of the community, that is, of the state. Modern institutions cut across earlier identities replacing old emotional and historical ties with different structures and beliefs for the new urban and industrial masses. Even the rise of fascism in Italy under Benito Mussolini in the early 20th century continued

the inclusive political nationalism of Italy’s independence heroes, Mazzini and Garibaldi, whose vision of a united Italy swept from the Sicilian South to the Alpine north in the 19th century. It was only in 1938 that Italian fascism added on an ethno-biological antagonism to its population of Jewish and Croatian origin (Sand p59).

Some emerging nationalisms, however, continued to cultivate ancient tribal ethnocentric myths about blood ties and the original ‘race people’, as the core. Political leaders called upon these reactionary myths to dominate the national mood in times of political upsurge and pressure. The rulers of Germany, Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine and Russia resisted the modernising call for a national identity on the political basis of citizenship. Bismarck’s consolidation of the German Federation into a new Germany utilised the ‘mythistory’ of a ‘people-race’ originating in the distant past to configure a modern military state that had to reconcile Catholics and Protestants, Prussians and Slavs, as well as Jews, within its new national borders. Above all, the state had to stamp its authority on the hopes of a new bourgeois class who demanded emancipation from the relics of feudal control. The wave of revolutions in 1848 led by liberals and radicals in Germany were defeated by violent suppression. Marx, Engels and others in the fledgling socialist movement were imprisoned, persecuted and expelled.

Zionism and heredity

The temporary defeat of class politics in Germany and central Europe ushered in a period of reaction in which the ruling class resorted to a reinvigorated racial nationalism, speaking of ‘blood and soil’. Zionist intellectuals likewise moved the ground of debate to racial lines. The new biological science of heredity was used to promote ethno-biological nationalism. The large Yiddish-speaking communities of east and central Europe became not only the victims of anti-Jewish pogroms, but also the object of contempt from the young Zionist movement. The rich, diverse cultural histories of the people of ‘Yiddishland’ (p247) were enclosed in the pseudoscientific terms of the ‘blood ties that exist in the Israelite family’ (p259). The founders of Zionism, Theodor Herzl, Max Nordau, Martin Buber and others, spoke about the national identity inherent in man’s ‘blood’. In the words of Vladimir Jabotinsky:

‘It is physically impossible for a Jew descended from several generations of pure, unmixed Jewish blood to adopt the mental state of a German or a Frenchman, just as it is impossible for a Negro to cease to be a Negro’ (p261).

This unapologetic appeal to blood and genetics was, and remains today, the foundation for the existence of the Zionist state of Israel. Indeed, the search for coherent blood lines continues, with efforts to use new DNA investigations to establish a genetic cohesion in the population of Israel. These have failed, of course.

Israel – the ethnic state

Building on his historical review of the emergence of nationalism, Sand concludes that the Zionist state is a nation built on the old ‘mythistory’ people/race model. The state does not act in the interests of all its citizens, and is not accountable to non-Jewish minorities. The Israeli state offers more protection and rights to every Jew in the world under the Law of the Right of Return than it does to Palestinians who are born from the generations that live there. While there are multiparty elections, political platforms are severely limited by a constitution based on blood ties to Judaism. Non-Jews cannot own land, cannot serve in the armed forces and cannot marry a Jew, and there is no civil marriage or burial in Israel. Sand concludes that there is no chance of peace in the future until the mythic race history of the Jewish people is discarded, along with anti-Semitism, in the dustbin of history. A highly recommended read.

Claudia Miller

* The term Zionism is used throughout to signify the belief that the land of Israel is the promised land of God’s Chosen People, the Jewish people. Page numbers refer to Sand’s book.