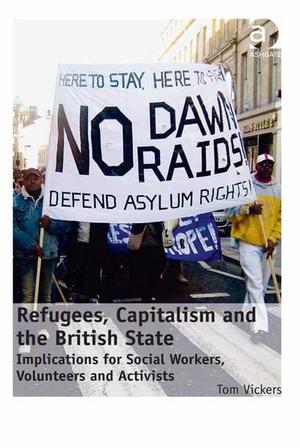

Review: Refugees, capitalism and the British state: implications for social workers, volunteers and activists, Tom Vickers, Ashgate Publishing, Surrey, 2012, £55 (website price £49.50)*

Review: Refugees, capitalism and the British state: implications for social workers, volunteers and activists, Tom Vickers, Ashgate Publishing, Surrey, 2012, £55 (website price £49.50)*

This is a book that delivers what is promised in the title and much, much more. Tom Vickers combines a detailed overview of current immigration policy at the legal and managerial levels, as it has emerged from successive British governments, with a Marxist understanding of the state. Refugees, capitalism and the British state is a work of direct significance to workers in the field of refugee experience and to all those who wish to understand the origins and significance of immigration in the context of the globalised power and financial structures of today.

The text is enriched by interviews which reveal the lives, thoughts and emotions of immigrants and asylum seekers, particularly when dealing with authorities. The author uses the term ‘refugees’ for all those who have come to Britain seeking refuge, instead of the official categories of ‘refugee’, ‘asylum-seeker’ and ‘refused asylum-seeker’, although he specifies whether an individual is with or without ‘status’ in the sense of some form of leave to remain in Britain where it is relevant to the case histories he presents.

Drawing concretely on the history of minority ethnic settlement in Newcastle and its environs from 1962 to 2008, Vickers explores the rise of the ‘refugee relations industry’ and in particular the impact of the ‘dispersal’ policy introduced in 1999. This great arc of time encompasses the postwar boom, with a securely established welfare state, and moves through the periods of the steady erosion of the coal, steel and manufacturing sector into a post-industrial services economy, concluding with the current banking crisis and cuts and privatisation of state welfare.

At the root of immigration is the question of the capitalist mode of production and its requirement to utilise labour power as the source of profit. Marx described capitalist relations of production which generate a ‘reserve army of labour’ to be drawn into work or thrown out when surplus to requirements; women, children and Irish workers are the prime historical examples. As Vickers demonstrates, the cultivation of an international reserve army of labour is a central characteristic of the latest period. ‘The costs of the labour power of migrants to the ruling classes of imperialist countries is reduced by the subsidy to the costs of its reproduction paid by migrants’ countries of origin, including in many cases the initial costs of training and education, and the costs of care during periods of non-productivity for capital in infancy and old age.’ (p13) Migrant labour constitutes therefore a section of the British working class, but one that is distinctively oppressed in income, benefits and conditions of work.

Immigration however does not occur simply as a response to the call for more and cheaper workers, (although this is precisely what happened after the Second World War when Britain recruited from its colonies). The ruling class also engages labour both at home and throughout the world to militarily support the invasion, domination and robbery of the natural resources of oppressed nations. In discussing Refugees and the British State, Vickers explains that Britain is ‘a particular kind of capitalist state’ (p64), that is, an imperialist state. This means that over and above ‘the principle of the right of ruling classes to regulate the territory and inhabitants within “their” country’s borders’, the states of imperialist countries ‘attempt to police the divide between the extremes of poverty, war and repression which characterise many oppressed countries where capital owned by the imperialist ruling class is invested’. War and military occupations in defence of imperialist interests have an impact on whole populations and result in the vast movements of people to escape terror, devastation and economic control of their homelands.

It is the role of the state to mediate not just between nations but also between classes and within classes, in order to sustain the overall power of the ruling class.. The whole system of managing refugees, with its attendant departments dealing with British citizenship, financing a ‘race relations industry’ and regulating state welfare is a part of the service that the imperialist state provides for the ruling class.

Divisions and contradictions in strategies for managing refugee labour reflect differing interests of sections of the ruling class that often run parallel. Consequently the legislative prohibition on refugees’ ‘right to work’ in 2002 coexists with domestic bondage, employment in sweatshops and other elementary occupations including permanent and seasonal labour in agriculture. The deliberate criminalisation of asylum-seekers and the creation of total dependency on food vouchers at the same time as the super-exploitation of refugees with depressed wages (at times no payment at all) are two of the forms of racism useful to capitalism today. Both Tory and Labour governments quickly resort to racist populism and appeals to patriotism and ‘Britishness’ to enforce divisions within the working class and divert anger away from the ruling class.

This study explores the racism, gender discrimination, disempowerment and coercion experienced by refugees in Britain today. There are fascinating descriptions of the self-help structures and organisations set up by volunteers, charities and activists in support of individuals and communities. These are politicised or depoliticised by a mixture interventions by the Home Office which, since 1999, has contracted out ‘front-line services delivery’ and ‘integration work’ to organisations like VOL which now employs 55 paid workers and about 300 volunteers. (p120). This institutionalisation of the ‘refugee experience’ has implications that the author sets out for the consideration of social workers, volunteers and activists.

The relevance of the experiences of the refugee minority to the whole of the working class is striking. The recent period has seen the extension of ‘work fare’ and unpaid ‘voluntary’ labour for young people in order to secure benefits in the future. In ‘a period of bank bail-outs and public sector cuts’ (p93), it can be seen that the ruling class will deal ruthlessly with any labour force and that the working class must be made to pay for the capitalist crisis. There can be few more powerful illustrations that working class solidarity with the most oppressed sections of society is the only foundation on which to build a defence against attacks on the working class as a whole. This book is a highly recommended read..

Susan Davidson

* Get your library to order a copy