Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! 238 April/May 2014

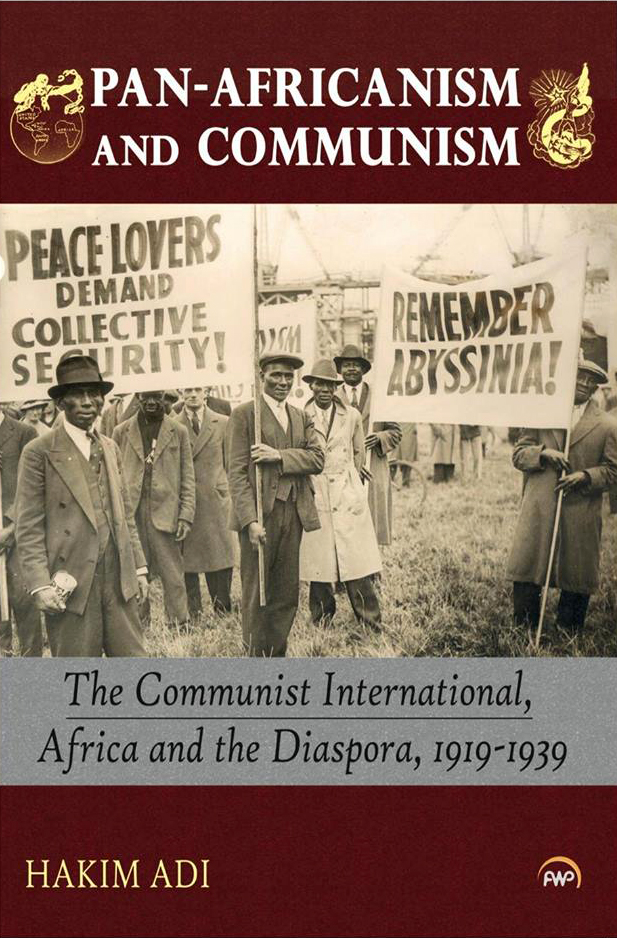

Pan-Africanism and Communism: The Communist International, Africa and the Diaspora, 1919-1939

Hakim Adi, Africa World Press, Trenton, 2013, 444pp, £28.99.

At 5am on 3 October 1935 Mussolini’s fascist army marched across the Mareb River into Abyssinia (modern Ethiopia), opening a war that would see Africa’s oldest independent country turned into an Italian colony. The invasion sparked mass protests across the globe, in many places led by the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (ITUCNW), a member organisation of the Communist International (Comintern) which for several years had fought to organise and unify ‘the wide mass of Negro workers on the basis of the class struggle’. In this book, the fruit of a decade of research, historian Hakim Adi provides a detailed exploration of the origins, politics and role played by the ITUCNW and Comintern in the anti-racist and anti-colonial struggles of black people throughout the early 20th century.

Adi begins by studying the development of a communist position on the struggles of black people against racism and colonial oppression. He turns first to the writings of Marx and Engels who recognised the economic and political importance of slavery, racism and colonialism for the capitalist class. In Capital Marx noted that ‘the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins signalised the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production’, while Engels condemned the European ‘scramble for Africa’ as a ‘subsidiary of the stock exchange’. Both understood the significance of anti-racist politics to the class struggle, neatly summarised in Marx’s famous conclusion that ‘labour cannot emancipate itself in the white skin when in the black it is branded’. As revolutionaries in both words and deeds, Marx and Engels became keen supporters of the abolitionist movement in the US and the anti-colonial movements in Egypt and Ireland.

With the development of world capitalism into its monopoly – imperialist – phase in the later 19th century the ‘colonial question’ assumed greater prominence among socialists, reflecting the upsurge in anti-colonial struggles in the oppressed countries.

In the aftermath of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution the newly-developed Comintern initiated serious debate within the communist movement about the importance of the colonial question. At the Comintern’s Second Congress in 1920 Lenin stressed the need for Communist Parties to ‘render direct aid to the revolutionary movements among the dependent and underprivileged nations (for example, Ireland, the American Negroes, etc) and in the colonies’, resulting in the creation of a special ‘Negro Commission’ and discussions over the ‘Negro Question’ at the Fourth Congress in 1922. These discussions, led by the black delegates Otto Huiswood and Claude McKay, resulted in a ‘Thesis on the Negro Question’, which emphasised that black people, particularly in the US, were ‘an integral part of the world revolution’. Comintern member organisations were committed to ‘closely applying the “Theses on the Colonial Question” to the situation of the blacks’, which included a set of concrete demands for political, social and economic rights.

However, despite this policy several Communist Parties continued to ignore the twin ‘Colonial and Negro questions’. During the Comintern’s Fifth Congress in 1924 the Communist Parties in Britain (CPGB), France (PCF) and the US (WP/CPUSA) came under rightful fire for this reason. The CPGB, representing a proletariat ‘more infected with colonial prejudice than all others in the Comintern’, still lacked a statement that unequivocally supported the break-up of the British Empire.

As the initial tremors of the Great Depression began to be felt across the world – and particularly acutely in the oppressed nations – chauvinist attitudes in the working class had to be urgently fought if meaningful revolutionary work was to progress. The venue for this battle was the Comintern’s Sixth Congress in 1928. In every debate over the nature of imperialism and racism the delegates of the oppressor countries and labour aristocracies – particularly Britain and South Africa – sought to minimise their importance, advocating a chauvinist ‘pure’ socialism that ignored imperialist reality. In every instance they were roundly defeated by the revolutionary trend, at the forefront of which were the outstanding black communists Harry Haywood and James Ford.

The debates at the Sixth Congress armed revolutionaries across the world – but most clearly in the US and South Africa – with a solid theoretical understanding that rooted the anti-racist and anti-imperialist struggle in the struggle for socialism. This revolutionary perspective was based on the understanding that the historical development of imperialism had given black people a dual oppression; on the one hand, they were oppressed as workers and poorer peasants, while on the other they faced a racial oppression. This racial oppression had a real material foundation in national oppression. As Haywood put it, ‘the special oppression of black people is the main prop of imperialist domination over the entire working class’; the struggle against racism was tied to the struggle against imperialism, and with it the struggle for socialism.

This book is an enormous research archive of the history of the Comintern and the ITUCNW. However the reader should not look to Adi to give answers to some of the political questions that were historically and are today still important issues. The relation between pan-Africanism and communism is not discussed but subsumed under the title of the book. The impression is given that the author seeks to define the Comintern’s position as ‘pan-African’ by simply redefining pan-Africanism as a neutral concept addressing historic oppressions of people of African origin and does not explain the class contradictions within these movements.

Adi’s project avoids political judgments but his work will serve as an excellent point of reference and source material for those who want to take up and continue the struggle against racism, against imperialism and for socialism.

Jack Edwards