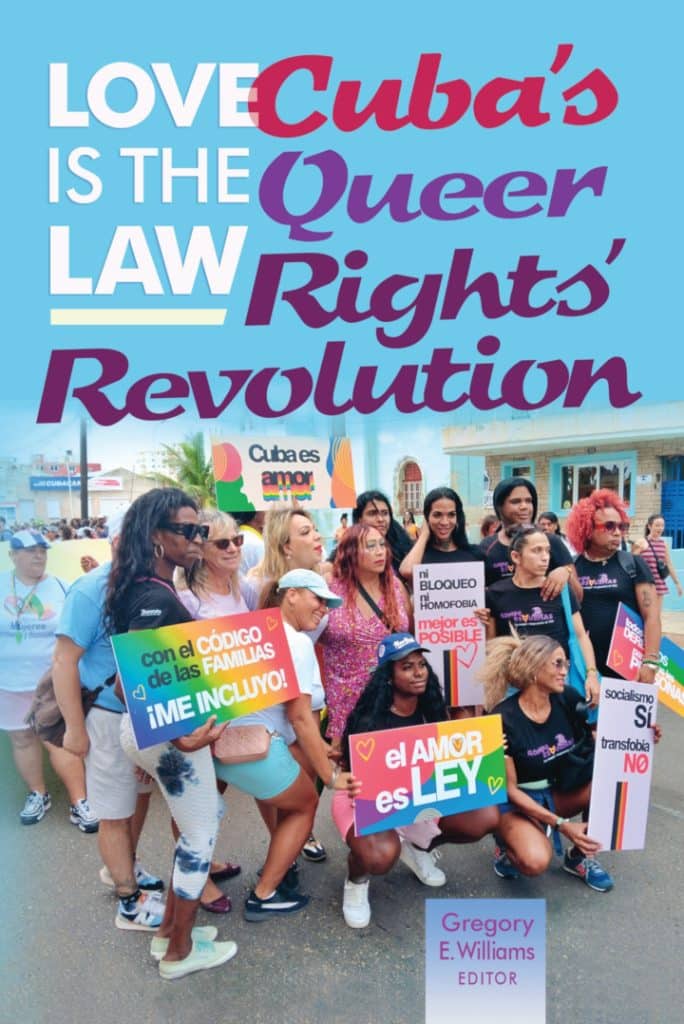

Love is the law: Cuba’s queer rights’ revolution by Gregory E Williams (ed), Struggle for Socialism – La Lucha por Socialismo, 2025, 307pp, £12 paperback

Cuba’s 2022 Family Code is a milestone achievement in LGBTQ+ liberation. However, as the anthology Love is the law makes clear, the Code delivers much more than same-sex marriage and adoption. It recognises the diversity of real world families – in which children are cared for by a single parent or by grandparents, in which bonds are biological or purely emotional – and commits to supporting all families based on mutual affection and responsibilities, not on patriarchal ‘legitimacy’ and ownership. As such, it represents not only progress for all Cubans regardless of their gender or sexuality, but also an advance in the ongoing construction of socialism through the empowerment of all members of society, and an end to the hegemony of the heteronormative nuclear family model essential to capitalist production.

Since the Labour government came to power the British state has ramped up its assaults on trans people, banning puberty blockers and, in the wake of the Supreme Court ruling defining women, rushing to effectively exclude trans people from public spaces and services including toilets, sports teams, and hospitals. Trans women face being thrown into male prisons where their risk of experiencing violence and sexual abuse severely increases. Love is the law – a collection of reflections by US-based LGBTQ+ activists who were part of a delegation to Cuba in May 2023 – details the actions being taken by the Cuban people and their socialist state to combat all forms of queerphobia, which are in stark contrast to the repressive actions of the US state. Democrat and Republican governments share culpability for measures including abolishing abortion rights; defunding AIDS prevention and treatment; cancelling trans people’s passports; and prosecuting teachers, healthcare workers, and parents who respect young people’s gender expressions.

Wisdom of the people

The Cuban people have democratically developed their constitution over decades, including enacting the 1975 Family Code, designed to empower women by dismantling capitalist gender roles. Its successes are many: today women make up 53% of Cuba’s parliament; women predominate in the science and technology sectors; and the number of women dying in childbirth has halved over the last 25 years, while in the US it has risen.

The Federation of Cuban Women contributed to the initial draft of the new Family Code, which was then presented to the public for discussion. In February-April 2022, 6,481,000 people (76% of the electorate) took part in 79,000 meetings in community centres across the country. Through a further 25 drafts, the people completely rewrote almost half the document. Additions made in the public meetings included clarifying inheritance rights for same-sex couples. By September, Cubans were ready to vote. All citizens aged 16 years and older were eligible. A turnout of 74% delivered a vote of 67% in favour of the new Family Code.

Included in the Code are: the right of same-sex couples to marry and adopt; parental status for grandparents or other relatives if they are a child’s primary carer; the right to free fertility treatment and surrogacy; equality for trans and nonbinary people; enhanced workplace protections for carers; equitable division of domestic labour within families; the banning of corporal punishment, and tougher penalties for those found guilty of domestic abuse. It defines the relationship of a parent to a child as one of ‘responsibility’ rather than ‘custody’, and it mandates that parents respect their children’s sexuality and gender expression.

Florida-based reactionary Cubans backed evangelical Protestant churches urging voters to reject the Code, for the same reason that billionaires fund evangelical movements in the US – not because of religious conviction, but to amplify anti-collectivist, pro-privatisation propaganda. Capitalists profit by exploiting people’s needs, and only the wealthy can afford fertility treatments or to give up work. In Cuba, now everyone has the opportunity for a family – there is no ‘trade-off of rights’, there is only free access for all – and it is this socialist model that the bourgeoisie long to destroy.

The road is long

The referendum is not the end of the process. Public meetings are still being held for people to discuss issues arising during the Code’s implementation. Far from dismissing the 33% who voted against, the National Centre for Sex Education is investing resources into predominantly rural No-voting communities, continuing conversations to ensure the whole population advances together in its understanding of gender and sexual equality as integral to wider working-class liberation.

The book is open about the culture of machismo that persists, including testimonies from Cuban activists who have experienced misogynist and queerphobic abuse. However, these same activists are clear that such attitudes are a relic of colonialism – ideologies justifying an economic system based on gendered division of labour – and that the solution does not lie in a return to capitalism, but in fortifying the road to socialism. Capitalist states keep workers divided and dispirited with threats or actual withdrawal of hard-won concessions such as abortion access or voting rights. But because under socialism progress is achieved by the working class working together in power, such progress is permanent. As Verde Gil Jímenez from the organisation Grupo Trans Masculino de Cuba says: ‘The road is long, but we trust that we will not advance alone. We have the advantage that the Cuban Revolution has founded a very valuable fabric of social and mass organisations and public institutions, with which we can articulate to design new projects and find solutions.’

Solidarity and struggle

Machismo is real, but as contributor Lizz Toledo points out, ‘the principal violence against Cuban women and other gender-oppressed people continues to be the US blockade.’ Among the many resources blocked are basic medications, menstrual products, condoms, toilet paper, hormone therapies, and gender-affirming surgeries. Life for individuals under such conditions is undeniably hard. But integrated services and socialist central planning have enabled Cuba to make collective gains that cannot be achieved under capitalism, for example in the field of medicine. Heberprot-P is a treatment developed for healing diabetic foot ulcers that has eliminated the need for diabetes-related amputations. 150,000 people per year in the US lose limbs because their government bans trade with Cuba.

This demonstrates that the blockade is not only an attack on Cubans, but on the working class everywhere. It enables the bourgeoisie to block not just medicines getting out, but also knowledge of the reality of socialism and the need for revolution. The text emphasises that while LGBTQ+ activists in imperialist countries must demand an end to the blockade and the removal of Cuba from the US list of ‘state sponsors of terrorism,’ the best way to show solidarity is to build socialism at home, which means forging alliances with migrant groups, disabled people, environmentalists, Palestine solidarity activists, and all other groups fighting imperialism.

While this revolutionary message is in the book, a stricter editorial throughline could have curbed some of the more liberal humanist sentiment that distracts from it. Nevertheless, Love is the law provides a thorough account for anyone interested in the progress of sexual and gender liberation in Cuba, which roots these achievements within the context of wider working-class struggle.

Felix Lancashire

FIGHT RACISM! FIGHT IMPERIALISM! 306 June/July 2025