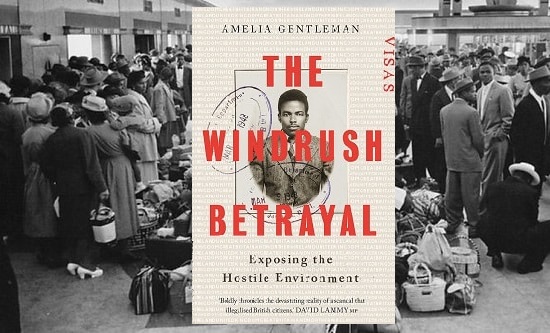

The Windrush Betrayal: Exposing the Hostile Environment, Amelia Gentleman, Faber 2019, £18.99 hbk

The Guardian reporter Amelia Gentleman tells the story of how she investigated what was happening to unknown numbers of older, long-term British residents, mostly Jamaican-born, who were suddenly notified that they were illegal immigrants and would be deported if they did not voluntarily leave the country immediately. She describes her struggle to contact the Home Office, the wall of silence she met and the confusion and despair of individuals and their families.

In fact, the personal histories Gentleman uncovers could all have been foreseen as the inevitable consequence of the ‘hostile environment’ legislation triggered by Theresa May in 2012, when she was Home Secretary.

As Gentleman goes on to show, from 2010 onwards immigration became a cauldron of political tensions, with the Conservative Party fearful of losing votes to Nigel Farage’s UKIP and an electoral bidding campaign, promising to bring numbers down to assuage an increasingly overtly racist right-wing press. The Con-Dem government of 2010 set up a special cabinet committee under the acronym MATBAPS (‘Migrants’ Access to Benefits and Public Services’). Its proposals were later incorporated into the Immigration Acts of 2014 and 2016.

In 2012 the Hostile Environment ministerial group was set up to enforce its directives within every state department and the DVLA. Theresa May attempted to outsource the work of immigration officials to the whole of the country, making it a citizen’s duty to report on other people. This was her solution to years of bungling by a dysfunctional Home Office too often embarrassingly exposed by the popular press.

New policies effectively made immigration enforcement officers out of landlords required to conduct right-to-rent checks, doctors assessing the immigration status of the sick before treating them, schools reporting on pupils’ country of origin; there were bank checks and driving licence checks; employers, universities and colleges, care homes and even charities and community centres were all instructed to send the Home Office information. Failure to do so could lead to a fine and even prison. A National Allegations database was set up to help ‘track illegal migrants down’. (p179) At the same time legal aid for migrants was virtually cut off, as were Citizens’ Advice offices. Added to this, in the summer of 2013, was Operation Vaken, a campaign involving involved billboards and leaflets that warned ‘Go home or face arrest’. Immigration enforcement vehicles lingered on the streets of multi-ethnic communities, generating a climate of fear.

For most of the people Gentleman meets, the first warning that they were ‘illegal’ arrived in a letter from the Home Office followed by automated text messages. Next, frightened employers dismissed them, universal credit was cut off, and hospitals discharged them or demanded payment for treatment. Many felt sure that there must be a mistake since they had lived in Britain from childhood, joining families who were indeed the original Windrush generation who arrived in 1948 on British passports. Most, in their 60s and 70s, had no memory of Jamaica, having lived and worked in Britain for over 50 years. The subsequent struggles to clarify their status with the Home Office became a nightmare of bureaucratic humiliation with repeated threats of imminent deportation. They were judged guilty and it was their responsibility to prove otherwise by providing four separate documents for each year of residence; national insurance and tax records did not seem to count, as people desperately scrabbled through their past to substantiate their schooling, jobs, marriages and children.

Following the publicity generated by a Guardian report of the incarceration of a 61-year-old grandmother, Paulette Wilson, in Yarls Wood in 2017, similar stories emerged. Retired Home Office staff recalled that hundreds of migrants’ landing cards had been destroyed. There was a slow realisation that huge numbers of people had been labelled ‘illegal’ and deported over several years. Gentleman travelled to Jamaica and met several who had been deported or forced out of Britain by financial deprivation, as well as those who had visited Jamaica for a family event only to be refused entry to their home on return.

Caribbean governments had long been concerned about the colonial treatment of black British citizens who had arrived as children. Questions were raised at the 2018 Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting and almost overnight ministers ‘were falling over themselves to express profound sorrow about the sufferings of the undocumented Commonwealth people’. (p 198) The Commonwealth nations had become more significant to a post-Brexit, globally trading UK and damage limitation measures were needed. With fulsome apologies about the ‘heartbreak’ caused, Home Secretary Amber Rudd set up a Windrush Taskforce, a party celebrating the 70th anniversary of the arrival of the Empress Windrush was held at Downing Street and a fund of £500,000 was suddenly found to set up annual Windrush celebrations.

However, the drivers of the ‘hostile environment’ intended to maximise deportations were still in place. Rudd had to resign after being caught out denying in parliament that deportation targets had been set. The next Home Secretary Savid Javid said that he would not set targets, but Boris Johnson’s Home Secretary, Priti Patel, has made no such commitment.

By 2019 Windrush Taskforce had been approached by over 7,000 people and over 6,000 have been granted papers confirming their legal right to be in Britain. A compensation scheme is expected to pay out between £200m and £570m to an estimated 15,000 people, although this is happening very slowly indeed.

The Windrush generation is now hypocritically portrayed by the ruling class and its media as ‘good migrants’ – the gallant and loyal community who helped rebuild Britain after the war. But the majority of migrants – workers used and then discarded as a flexible work force –remain subject to the hostile environment. A fuller understanding of the role of migration in the capitalist economy can be found in Borders, Migration and Class in an Age of Crisis by Tom Vickers*. Amelia Gentleman’s book is highly recommended as a contemporary document of the times in which we live and the battles we have to fight.

Susan Davidson

* Borders, migration and class in an age of crisis, Tom Vickers, Bristol University Press 2019, £26.99 hbk or order a copy from Larkin Publications for £20+p&p.