5 March 2005

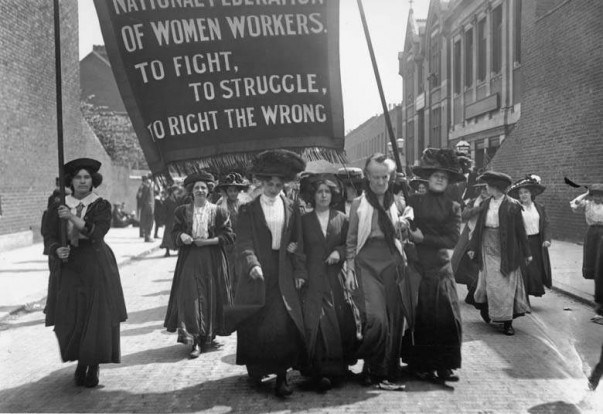

I would like to bring the greetings of my organisation, the Revolutionary Communist Group, to this meeting in celebration of International Working Women’s Day. This speech is in three parts. Firstly, I am going to talk about specific struggles of working women in this country during the past 20 years; secondly, I am going to say something about women prisoners; finally I am going to explain a little about the political stance of my organisation.

1. The past 25 years in Britain since that very unrevolutionary woman, Conservative leader Margaret Thatcher, came to power have seen a huge change in the social structure of the country. Previously, rich because of its imperialist plunder; the state could guarantee a sizeable section of the working class lifelong employment, affordable housing and welfare provision. Thatcher announced there was ‘no such thing as society’, only individuals and made it clear she was declaring war on the working class.

Since then, under both Conservative and Labour governments the attack has continued unabated. Public services have been privatised and are unashamedly run for profit; large sections of manufacturing industry have been destroyed; trade union membership and organisation are now largely the domain of white-collar workers; council housing has been sold off; free health and education progressively run down.

Women workers have suffered disproportionately, as they have been more likely to be employed in temporary or part-time work, with fewer rights and less opportunity to organise. At the same time, as main carers for children and the elderly, women have been most effected by the running down of welfare provision and health services.

Not surprisingly, many of the struggles during this period have been defensive – rearguard actions fighting to salvage something of the old order. However, they have also thrown up new forms of organisation, and new alliances have been forged. These give us hope for the future.

Among Thatcher’s first targets were the Irish national liberation struggle and the British coal-miners. In Ireland, women had been playing a key role for many years, both as fighters and as the organisers of ‘relatives action committees’. After the IRA unsuccessfully attempted to wipe Thatcher and her Cabinet out in the Brighton bombing of 1984, two Irish women convicted of involvement in that attack were imprisoned in England and subjected to a form of gender-specific torture, in the form of repeated strip-searches. A principled campaign against this managed, with difficulty, to unite feminists and nationalists.

The miners’ strike of 1984-5 was a heroic struggle against the government’s drive to close pits and privatise the industry. Although the miners themselves were exclusively male, women from mining communities flocked to picket the pits and were at the forefront of the organisation of solidarity with the strikers. Free from the restricting influence of traditional trade union organisation, the ‘miners’ wives’ made links with all those offering solidarity. They visited Belfast and understood how mining villages now under siege from the police were similar to Republican areas occupied by the British army. They joined forces with pacifist women camped outside the US’s military base in the UK, at Greenham, who in turn learnt from the miners’ wives about class struggle.

The miners were defeated. Sold out by the Labour Party and trade union movement. But the unity forged by the miners’ wives is part of our legacy for any struggle built in the future.

In 1992-1993, 19 workers, mainly Asian women, were on strike for a year, at Burnsalls electro-plating metal factory in Birmingham, demanding union recognition, health and safety measures, equal pay for women, a reduction in their working week, which with compulsory overtime averaged 55-65 hours.

The strike attracted solidarity from anarchists, communists, women’s activists and anti-racists, who formed three solidarity groups. However, the union, the GMB, although formally supportive, insisted the fight be limited to small pickets and an industrial tribunal case. It opposed rallies, marches and the very existence of a support group that linked the industrial struggle of the Burnsall workers to the multi-layered oppression the majority of them faced as immigrant women workers in Britain. Ultimately, the union sabotaged the campaign, worked with the police to prevent a march going ahead, and sold out the strike. The lessons from that episode were bitter ones.

Since that strike, there have been other similar struggles led by women workers – the Hillingdon Hospital cleaners, the Tameside careworkers, for example. It has become clear that the old alliances with what is left of the official trade union movement have little to offer to those who take a brave stance against privatisation and casualisation.

2. I want to turn now to a very different aspect of women’s situation in Britain. We are hearing today about the bravery of the Turkish women political prisoners and we are sending solidarity cards to women political prisoners in various countries. I want to talk now about Britain’s non-political women prisoners. I want us to understand that, in the situation that I have described, in which the poverty gap is widening and society becoming more fragmented, the women who fill the gaols here today, although far from being conscious political prisoners, are undoubtedly the prisoners of bourgeois politics.

This country has the highest prison population in Western Europe. Although women make up just over six per cent of the total, their imprisonment has nearly tripled during the past 15 years. At any one time, there are approximately 4,500 women in prison in England and Wales (Scotland and the occupied north of Ireland are counted separately.)

Over half of women prisoners have children under 16. 8,000 children every year have their living arrangements disrupted by their mother being imprisoned. Women’s imprisonment attacks working class families and communities.

Approximately a third of women prisoners are not British citizens; many have been arrested on entry for drug importation or passport violations. They face deportation as well as imprisonment. Their situation graphically demonstrates the inter-relationship between class, gender and racial oppression.

The rate of suicide and self-harm among women prisoners is very high. Last year 15 women took their own lives. Pauline Campbell, the mother of one young girl who died in 2003 has begun a campaign to highlight the situation and has been organising demonstrations outside women’s prisons.

There is an urgent need for the political movement not to leave such campaigns to liberals and lawyers, but to become involved, pointing out how class, race and gender oppression are linked. Women who die needlessly in British prisons are our ‘disappeared’. A principled struggle in their memory and in solidarity with women in prison would be a significant step.

3. The Revolutionary Communist Group is a Marxist-Leninist organisation that was founded in 1974. In 1979 we launched our newspaper Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! We called the paper by that title to make the point that as Britain is an imperialist nation, which lives off plundering oppressed nations, it is impossible to fight racism here without opposing imperialism internationally. We put this into practice by linking campaigning in solidarity with movements for national liberation – at that time in Ireland and South Africa, later in Kurdistan, today in Palestine – with the struggle against racism in Britain.

We take a similar approach on the question of women’s emancipation, arguing that without a struggle against capitalism and imperialism, women cannot be liberated. Today, one of the main activities that the RCG is involved in is in solidarity with the Cuban Revolution, a revolution that we believe illustrates in practice how it is possible to build socialism. In 1996 our comrades interviewed Assata Shakur, a former member of the revolutionary US Black Panther Party, who escaped from gaol in the US and lives in political exile in Cuba. She described how when she came to Cuba she realised that ‘a revolution is a process’ and although in Cuba ‘sexism had not totally disappeared, nor had racism… the revolution was totally committed to struggling against racism and sexism in all their forms.’ Assata said that ‘You cannot wipe out racism or sexism unless you have some kind of system that guarantees basic human rights and food and shelter…’

This does not mean, as some Trotskyist political groups have said in the past that the struggle against women’s oppression, or the struggle against racism, should somehow be put on hold, made to wait until ‘after the revolution’. Such groups contend that fighting for women’s rights here and now is somehow a bourgeois distraction or deviation from the class struggle.

Instead, what it means is that the struggle for working class emancipation must always include the struggle against women’s oppression, and the struggle against racism. They cannot be separated from it.

Women’s oppression under capitalism is manifested both through inequality in the work place and inequality in the home. Women’s role is both that of servicing the labour power that capitalism thrives off – by caring unpaid for our husbands and sons so they can work; and that of a reserve army of cheap labour so that we too can be called upon to work as capitalism dictates. Our demands as women workers have to address both these areas: we struggle therefore both for equal pay and employment, and for better childcare provision, access to contraception and free abortion on demand.

I’d like to end on an international and historical note, with a quote from Soviet women’s leader, Alexandra Kollontai (1909):

‘The more aware among proletarian women realise that neither political nor judicial equality can solve the women’s question in all its aspects. While women are compelled to sell their labour force and bear the yoke of capitalism…they cannot become free and independent persons, wives who choose their husbands exclusively on the dictates of the heart, and mothers who can look without fear to the future of their children. The ultimate objective of the proletarian woman is the destruction of the old antagonistic, class based world and the construction of a new and better world in which the exploitation of man by man will have become impossible.’

Nicki Jameson