‘I am not here then as the accused; I am here as the accuser of capitalism dripping with blood from head to toe’ (Maclean, 1918)

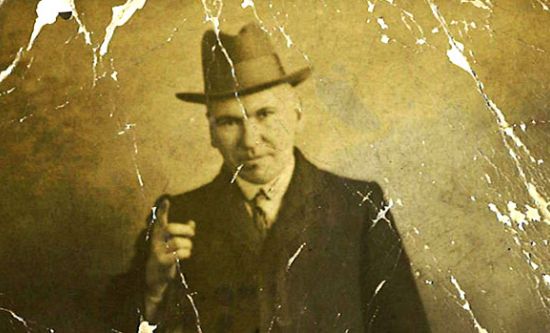

John Maclean’s defiant ‘Speech from the Dock’ at his 1918 sedition trial thunders across the century as imperialist barbarity in Palestine appals the world today.

Maclean died on St Andrew’s Day, 30 November 1923. He was 44, and had been at liberty from his latest incarceration for only the previous 11 months. Fatally weakened by five terms of imprisonment, force-feeding and drugging, his final sentence of one year had been imposed after he advised a crowd of unemployed people in 1920 not to allow themselves to starve but instead to take the food they needed.

From the very first day of the First World War on 4 August 1914 he had declared opposition to the gangs of capitalists carving up the world for their profits. Imperialism had dragged humanity to the new slaughterhouse of global war and conquest. Millions of working-class people had already perished to satisfy ruling-class greed. ‘War against the Warmakers’ was the cry. Those who challenged imperialist war faced the prison cell or firing squad. Maclean was sentenced to three years in April 1916 for open and militant opposition to the war. At that moment James Connolly was leading the revolutionary challenge to warmongering British imperialism’s rule in Ireland. Maclean was to distinguish himself in the socialist movement, as the foremost advocate of Irish self-determination. His damning statement of how Britain maintained that rule would adequately describe Israel’s rule in Palestine: ‘To any right-thinking person Britain’s retention of Ireland is the world’s most startling instance of a “dictatorship by terrorists’’…’.

In Lenin’s revolutionary April Theses of 1917 Maclean was recognised as having been: ‘sentenced to hard labour by the bourgeois government of Britain for his revolutionary fight against war’. In October that year, the socialist revolution in Russia decisively undermined that imperialist war. Maclean’s courageous political stance was further recognised when he was appointed Soviet Consul in Glasgow in 1918.

Maclean’s revolutionary life was, from the beginning, the expansive and determined practice of his Marxist understanding of capitalism and class struggle. As a socialist he directly engaged with workers in economic struggle. In 1907 he was invited by the Irish revolutionary trade union leader, James Larkin, to sit in on negotiations during the historic Dockers Strike in Belfast. On learning that strikers had been killed and injured by British troops he cried ‘murder’ and declared: ‘Ireland’s fight started in 1907 during the Belfast dockers’ strike.’ He stood by low-paid women strikers – and against union scabs – in 1910 and wrote approvingly of their energetic tactics: ‘The march, with a great banging of tin cans and shouting and singing, pursued its noisy way from Neilston to Pollockshields, where the respectable inhabitants were thoroughly disturbed’. These workers were also challenging the respectable trade unions, who then as now attempted to bury more militant working class action.

Then, as now, those trade unions were not seriously interested in those without work and facing hunger. Asked at one trial how he had come to be organising the unemployed, Maclean replied with characteristic directness: ‘Because no one else would!’ From leading a march through Glasgow’s Stock Exchange, to sharing out collections from demonstrations outside churches, to his final sentence, he refused to narrow the issues facing the working class to trade union issues. His politics and activism taught him that the class struggle for socialism was based on a far wider and deeper understanding, and this fully determined his actual practice. The unemployed movement he and his small, ragged band of comrades built had self-determination for Ireland and India among its demands. Through rent strikes, through battling for democratic rights, through challenging injustice in prisons, to popularly advancing the fullest Marxist understanding of capitalist exploitation and competition, to centrally opposing imperialism, Maclean fought on.

Ireland’s fight was socialism’s fight and Maclean’s fight. In that battle he demonstrated his insight into the source of ruling class power and violence and its weakness. In July 1920 he appealed for the broadest unity and support against Britain’s brutal war on the Irish people: ‘This is more important than protesting against higher rents or the high cost of living.’

As millions pour out onto the streets to stand by Palestine in a way no protest against austerity has so far, the new movement must learn how Maclean fearlessly upheld the banner of anti-imperialism, class struggle and revolutionary socialism.

Long live the memory of John Maclean!

Michael MacGregor

FIGHT RACISM! FIGHT IMPERIALISM! 297 December 2023/January 2024