FIGHT RACISM! FIGHT IMPERIALISM! No. 119 JUNE/JULY 1994

Every city has one; Britain sends more people there than any other European country, but prison as we know it is a relatively new innovation. NICKI JAMESON and TREVOR RAYNE examine the history of this instrument of state power.

Incarceration as a systematic and universal punishment began only with the Industrial Revolution. It sought to discipline the working class to accept the conditions that capitalism determines for it. Consequently, prison is also an instrument used to isolate and hammer working class leaders. Prison policy combines liberal reform, emphasized in stable times for capitalism, and vicious retribution, emphasized when crisis looms for the ruling class.

Emergent capitalism forced the means of production out of the hands of labour and enforced ‘a degraded and almost servile condition on the mass of the people, their transformation into mercenaries and the transformation of their means of labour into capital’ [Marx]. From the Tudor period onwards a growing army of unattached proletarians was hurled onto the labour market by the dissolution of feudal retainers, abolition of monasteries and enclosure movement. Imprisonment and terroristic punishments were used to discipline this ‘army of beggars, robbers and vagabonds’ into acceptance of waged labour. During the 16th century land values increased and enclosures accelerated. The 1601 Poor Law established ‘Bridewells’ or ‘Houses of Correction’ to lock up petty criminals, vagrants and the poor to teach them to lead more ‘useful’ lives through forced labour.

Crime…

By 1770 three-quarters of all agricultural land in England was owned by 4-5,000 aristocrats and gentry. Alongside the enclosures and dispossession of the rural populations there developed a new emphasis in the treatment of crime. Previously, offences against people were considered most serious — and the higher up in society the victim, the more serious the crime; the new ‘serious crimes’ were committed against property. The range of capital offences increased so rapidly criminal law became popularly known as the Bloody Code. Anything posing even a minor threat to the emerging rural landlord and capitalist classes, such as poaching or forgery, became a hanging matter.

The urban population swelled with the dispossessed. They were dangerous to the newly triumphant capitalism — poor, unintegrated, disrespectful and volatile. E P Thompson writes of the second half of the 18th century: ‘One may even see these years as ones in which the class war is fought out in terms of Tyburn, the hulks and the Bridewells on the one hand; and crime, riot and mob action on the other.’

… and punishment

Following the 1789 French Revolution the ruling class lived in terror that the upheaval would spread to Britain. Public executions had become carnivals in which the condemned played the hero; the mere assembly of such large crowds at executions was seen as a danger. Similarly, punishments based on public humiliation, such as the stocks, fell from favour as community could no longer be relied on to aim the rotten fruit, stones and insults at the intended victim, targeting the attendant magistrates instead!

Throughout the late 18th and early 19th centuries there were crime waves, part real, part imagined by a ruling class which lived in fear that ‘the mob’ would rise out of the sewers and destroy its property and privilege. Fear of crime and of political upheaval were conflated, ‘the mob’ and Jacobinism’ interchangeable bogeymen. The Wilkes Riots of the London ‘mob’ in the 1760s and ’70s, in which the call for people’s rights was mobilised in the interests of the City; the Gordon Riots of 1780, ostensibly against ‘Popery’ when London became a ‘sea of fire’; these and countless other episodes revealed ‘a groping desire to settle accounts with the rich, if only for one day’ (George Rude, Wilkes and liberty).

The authorities felt powerless: they could not execute more people for fear of sparking even greater upheaval. Juries and magistrates, appalled by the severity of punishments they were expected to mete out, began refusing to convict or deliberately convicting on lesser charges. Even the prosecution would resist seeking the death penalty for small offenders, their consciences encouraged by fear of their houses being burned down.

Before the Industrial Revolution, prison was primarily used to hold people before trial or punishment by ducking, flogging, disfiguration, the stocks, transportation or death. At the Old Bailey between 1770-74 just 2.3 per cent of sentences were custodial; most were for weeks or months and the maximum was three years; 66.5 per cent of sentences were for transportation to the Americas for seven years, 14 years or life. The situation was brought to an acute crisis with the loss of the American colonies: between 1776 and 1786 there was a 73 per cent increase in the prison population; custodial sentences increased from 2.3 per cent to 28.6 per cent. The prisons experienced outbreaks of fever, riots, escapes and the government was besieged by petitions from prisoners demanding release, transfer or improvement in conditions. The search for new methods of social control became urgent.

‘Reform’

Under the twin banners of philanthropic reform and rational scientific progress, John Howard, author of The State of the Prisons in England and Wales (1777) and the namesake of today’s Howard League for Penal Reform, set out to prove that, ‘There is a mode of managing some of the most desperate with ease to yourself and advantage to them. Show them that you have humanity and that you aim to make them useful members of society.’

Howard toured the country’s prisons and found convicted prisoners in chains, disease rife, richer inmates renting rooms while the poor slept in squalid dormitories. Visitors came and went bearing food; alcohol, sex (freely-given or purchased) and gambling were easily accessible. He evolved the idea of a ‘penitentiary’: silent, hygienic and austere, where criminals would live and work on their own, uncontaminated literally and figuratively by contact with others. They would both be retrained and re-educated to lead law-abiding lives and, through contemplation and religious instruction, feel guilt and remorse and so forsake crime.

Like all reformists, Howard and his contemporaries understood that excessive brutality and obvious injustice called into question the legitimacy of the entire system, to a point where opposition of a revolutionary character might shake the very foundations of the established order.

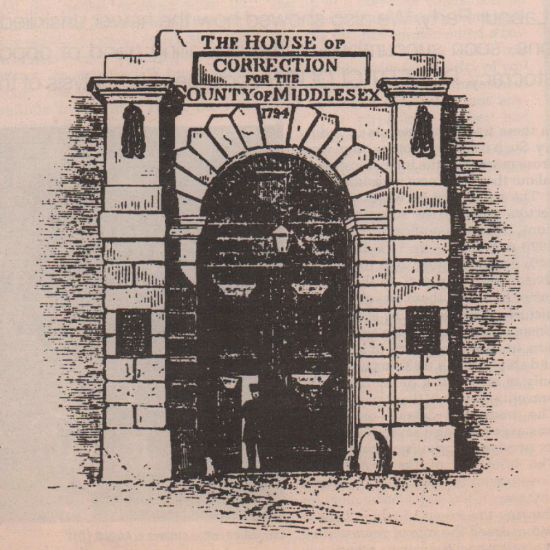

Cold Bath Fields and Millbank

‘As he went through Cold Bath Fields he saw a solitary cell; And the devil was pleased, for it gave him a hint, Of improving his prisons in Hell.’ Southey and Coleridge —The Devil’s Thoughts

After the passing of the Penitentiary Act, drafted by Howard, Eden and Blackstone, in 1779, there was a delay of over 30 years before the building of Millbank, Britain’s first state prison, in 1812-16. Following the French Revolution, the ruling class did not want to be viewed as retreating from physical retribution or associating with ideas of reform and rehabilitation. However, new gaols were built under local auspices. The largest was Cold Bath Fields in Clerkenwell which opened in 1794. It contained a shot drill yard, where prisoners carried cannon balls up and down stairs, and six treadwheel yards. A prisoner was expected to turn the wheel the equivalent of 12,000 feet of ascent a day. This regime so damaged the health of inmates that the Royal Artillery refused to send offenders there as they returned unfit for duty. Eventually the ascent distance was reduced to 1,200 feet per day.

When the Millbank finally opened it was Europe’s largest gaol, capable of holding 1,200 prisoners. The regime combined Howard’s ideas of religious instruction, hard labour and solitary confinement, but was short-lived. Brutal gaolers and rebellious prisoners saw to that. Flogging was soon introduced and the gaol became overtly repressive. Prisoners were forbidden all reading material and their diet steadily reduced until in 1823 31 prisoners died of typhus, dysentery and scurvy and 400 were taken seriously ill.

Prisons were regularly targeted by the ‘mob’ and their inmates released. Similarly, on the inside, prisoners would rise up as at Gloucester prison in 1815, Millbank 1818 and 1826-27, Portland, Chatham etc. In 1800 a protest by prisoners at Cold Bath Fields attracted massive support from the workers of Clerkenwell. They milled around the walls, shouting encouragement to the prisoners who called down to the people to tear down the walls. Chants of ‘Pull down the Bastille!’ began to rise from the crowd, who were only dispersed by the combined forces of the Bow Street Runners and a hastily mobilised group of local property owners, the Clerkenwell Volunteers, using a cannon positioned in front of the prison gate.

Class struggle

As the ideas of Tom Paine and the French Revolution were taken up by the Radicals in Britain, so prisons were used to try and silence them. Stamp duty on publications and extended powers to prosecute ‘sedition’ resulted in many imprisonments. Richard Carlile continued to edit The Republican from gaol. He was supported by 150 volunteers who, between them, served 200 years of imprisonment in defiance of the law. Up to 750 people were prosecuted for ‘unstamped’ material be-tween 1816-36.

The Chartists, established 1837-8, with their principal demand for universal adult male suffrage, had their leaders like Feargus O’Connor and Ernest Jones imprisoned. A Chartist-led revolt in 1842 resulted in 146 people being sentenced to prison with hard labour in the Potteries alone. After the last great Chartist march in 1848, almost 500 were arrested and sentenced to terms of imprisonment.

By now imprisonment was the main punishment for all offenders (except those sentenced to death), together with the crank, the tread-wheel and penal servitude. For the first time sentences over three years came into use along with the ‘ticket-of-leave’ system, the precursor of parole. Pentonville prison was built in 1842, using the ‘panopticon’ design, conceived by Jeremy Bentham, whereby a centrally placed observer could survey the whole prison, as wings radiated out from this position. Over the next six years 54 new prisons were built using the panopticon design, which was also employed for mills where a foreman could simultaneously oversee the whole workforce.

State power

In 1877 the prison system was unified into a single state-run service. Integral sanitation was abolished and all the toilets removed from Pentonville. Press and public were banned from setting foot in the prisons. Prisoners were required to face the wall when not in their cells or wear masks and maintain absolute silence. In this way they could not identify or recognise one another; nor could they organise. If they transgressed they were punished by being put in a pitch-black cell, fed only bread and water and flogged.

As the system became entrenched, certain changes were made to it, usually under the cloak of ‘reform’. The use of entirely dark cells was discontinued in 1884. Hard labour was partially abolished in 1898 in favour of ‘productive labour’ and abolished entirely in 1948 along with flogging, which ceased to be a punishment ordered by the courts but continued to be administered against inmates who assaulted prison staff until 1968. Separate confinement was officially abolished in 1922 but its use continues as a means of punishment for `subversion’ to this day.

The Industrial Revolution stamped its marks on every town in Britain: the factory, the mill and the prison. But by building these institutions into which the proletariat was cast in ever increasing numbers, the conditions were also created for opposition: the factory and the mill had their strikes, the prison its riots. Few skylines are dominated today by Victorian mills and factories, yet the prisons still stand and new ones join them every year. They are still used to threaten, bully and isolate the working class; the balance between psychological and physical punishment is still tipped this way and that; the debate between different sections of the ruling class about whether the gaols are for reform or for punishment continues. And the objects of their deliberations still reject their treatment, still protest, still riot, still fight back. Thankfully.