It is ten years since prisoners took over the chapel of Strangeways prison, Manchester in protest at the degrading and brutal treatment which was rife not just in that prison, but in almost every ‘local’ gaol throughout the country. Prisoners on remand or serving short to medium-length sentences would be cooped up for 23 hours a day, three to a cell, with no sanitation and extremely limited access to the outside world in any shape or form. As if this were not enough, they were subject to a constant barrage of intimidation, both verbal and physical, from thuggish prison officers, who treated prisoners worse than animals and considered themselves accountable to no-one. Assaults were a daily occurrence, as was the forcible injection of tranquillizing drugs.

The protest in the chapel rapidly spread to the whole prison. Large parts of the gaol were destroyed and a small group of militant prisoners remained on the roof-top for 25 days. The uprising was the biggest and longest prison protest in British history and sent shock-waves throughout the whole prison system, with disturbances in over 20 other prisons. Despite vitriolic press coverage, there was massive sympathy and tacit support from thousands of people, many of whom had had their own experiences of the inside of local gaols. In the articles below, three prisoners who were at Strangeways in April 1990 assess the progress, or lack of it, since then, and an FRFI comrade who was involved in supporting the prisoners and their families recollects the inspirational nature of the protest.

No lessons learned

The rebellion at Strangeways in 1990 created an initial liberalisation of the prison system, represented by the Woolf Report, and a clear recognition on the part of the system that progressive change in the treatment of prisoners was desperately required if further rebellion was to be avoided.

The causes of the Strangeways rebellion were deep-rooted and stemmed from the refusal of the system to recognise that prisoners, whatever their crimes, were entitled to be treated as human beings with basic inalienable human rights.

Unfortunately, it required an open rebellion to persuade the prison system that treating prisoners as animals was no longer viable in terms of control. The brief liberalisation of penal practice and debate following Strangeways was resisted by certain elements in government and the Home Office and, following the appointment of Michael Howard as Home Secretary, these elements regrouped and went on the offensive.

Using the excuse of the Whitemoor and Parkhurst escapes of 1994/5, Howard and his followers instigated a set of policy changes that were to transform prison regimes in the most negative way and shift the balance between rehabilitation and security clearly towards the latter. No longer would even a vestige of humane treatment be allowed to interfere with a determination to ‘get tough’ on prisoners and make gaols impregnable.

Under a new so-called Earned Privileges Scheme, prisoners now had to ‘earn’ access to basic rights and privileges by ‘good behaviour, usually interpreted by prison staff to mean total obedience to their power and authority. Prisoners were now categorised into three ‘Privilege Levels’: Basic, Standard and Enhanced. This effectively created a sort of class system designed to divide and rule prisoners. In some gaols those prisoners on ‘Basic regime’ are held in conditions indistinguishable from those in punishment units.

The Incentives and Earned Privileges Scheme is a control mechanism that operates in a completely arbitrary way and allows prison staff to legitimise their victimisation of perceived ‘troublemakers’ and ‘subversives’.

Also central to the strategy of control was the creation of control-unit type regimes in prison segregation units, which are specifically designed to subdue and break the spirit of prisoner activities. The brutalisation of prisoners held in segregation at Wormwood Scrubs was an obvious symptom of this approach and is just the tip of an extremely large iceberg.

The creation of the already infamous Woodhill Close Supervision Centre for disruptive prisoners is another symptom of the official determination to eradicate resistance among prisoners and prevent disturbances on the scale of Strangeways. Overall the level of control and security exerted over prisoners has now become all-pervasive and total, and an atmosphere of outright repression prevails in most penal establishments.

The lessons that should have been learned from Strangeways, ie fair and humane treatment and access to natural justice, have been ignored and jettisoned, and instead there is a determination to crush and destroy the will of prisoners to protest and complain.

This oppressive approach manifests itself in every area of prisoners’ lives but while the prison system pursues its current strategy of screwing down gaols, the resentment and anger of prisoners is growing and the spectre of another Strangeways is very apparent. As before the Strangeways rebellion, prisoners are being pushed and driven to the very limit of their endurance and it won’t be very long before they begin to push back.

Tony Bush, HMP Altcourse

Tony was sentenced to nine years’ imprisonment for his participation in the Strangeways revolt, plus 18 months for escaping from Manchester Crown Court during his trial.

Brutality, bullying and degradation

The Strangeways uprising resulted from our living conditions and the brutality, bullying and degradation we were subject to from prison officers. There is a real need to recognise the Prison Service always promoted living conditions as the cause of the uprising, yet makes no mention of the brutality, fear, humiliation and institutional bullying within the prison system, which were in fact the primary cause of the uprising. Living conditions were an issue, but not the issue.

The Prison Service prefers living conditions to be seen as the cause because recognition of the primary reasons behind the uprising would have brought into question the need to introduce a system where prison staff are accountable for their behaviour, rather than continue with the current system and its pseudo-accountability which allows any abuse to go unchecked.

Following the Strangeways uprising, brutality drastically declined, humiliating and degrading treatment virtually ceased, real progress was made in the humane treatment of prisoners. But in the mid 1990s high profile escape attempts were used as a reason for a return to brutality, humiliation, degradation and institutional bullying, all in the name of security. A decade after the Strangeways uprising the same issues have returned.

Stewart Bowden, HMP Long Lartin

Stewart was not tried for involvement in Strangeways, but his presence on the first day of the protest has continued to be held against him by the prison system. He has been charged and twice acquitted of Prison Mutiny at Full Sutton prison.

Hypocritical system

The Strangeways incident of 1990 was a momentous event, which will echo through the years to come. It has been a decade since that event and what gravity of change positive and negative that decade has brought. I am only equipped with my own experiences, although attention is given to those I have had the pleasure of being acquainted with, who have experienced and still are experiencing various acts of brutality, oppression, racism and the typical prison system way of functioning by means of resentment and antagonism.

Since Strangeways I have been confronted with these extremes and more, even to the extent where scumbag warders have attempted to maim and kill within the confines of segregation units. Such treatment is still enmeshed within the system and it is illogical to expect other employees of the system – teachers, psychologists, psychiatrists – to deplore it, as they all acquiesce. The functioning of the Prison Service is backward and the rules are designed to undermine prisoners’ capabilities, particularly through courses which they are threatened into attending. Here in Frankland prisoners who are appealing are told by Sentence Planning Boards: admit your guilt – it could be beneficial! Failure to admit results in removal from Enhanced privilege level to Standard.

With regard to my personal circumstances, I have now served 20 years of a life sentence and still have no prospect of release, maybe because I remain physically and mentally strong and am not prepared to go under in the face of this hypocritical system. They are good at making rhetoric when pointing fingers at other nations which commit barbaric acts and treatment but then such has been the practice of the British establishment throughout history.

Alan Lord, HMP Frankland

Alan was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1980 and could reasonably have expected to have been released by now; however in addition to the 11 years concurrent imprisonment he was given for his presence at Strangeways, the prison system is using the expandable provisions of the life sentence to render his chances of release almost non-existent.

Memories of Strangeways

I remember turning a corner in the road to the gaol and looking up at its hideous shape. The sight of tiny figures, sitting, playing, enjoying themselves, was amazing like a huge fist in the face of the Prison Service.

There were a few people standing over the road and after meeting up with a comrade I decided to sell some papers. My first attempts were met with suspicion, but when I explained that we were there in solidarity with the prisoners, faces warmed: ‘Me too’, was often the response, ‘I know what it’s like in there’. Nothing more needed to be said; it was like a silent tribute.

Sometimes the weather was sunny but other days were awful. One Sunday afternoon it snowed! There was a small group of picketers and we spent ages joking and laughing with one of the prisoners who had managed to crawl along a very narrow part of the roof almost overhanging the road. He didn’t even have a jumper on and was apologetic about leaving us when the cold finally got to him.

The best times were with the relatives. I remember after one press conference, going for a drink with some mothers and girlfriends of the prisoners. ‘Tell us about communism; what is it?’ They were so impressed and incredulous that FRFI would tell the truth and support them and their loved ones, not tell the lies of most of the media.

And the pickets the RCG helped organise with the relatives were strong. One young woman really laid into some screws prowling nearby and they scuttled off. There were grandmothers and mothers holding up babies and toddlers ‘to see dad and send him your love’. Some of those children must be teenagers now. I hope they’re proud of their fathers.

On estate sales in Manchester at the time I can remember seeing children climbing on walls pretending to be the men on the roof of Strangeways.

FRFI 154 April / May 2000

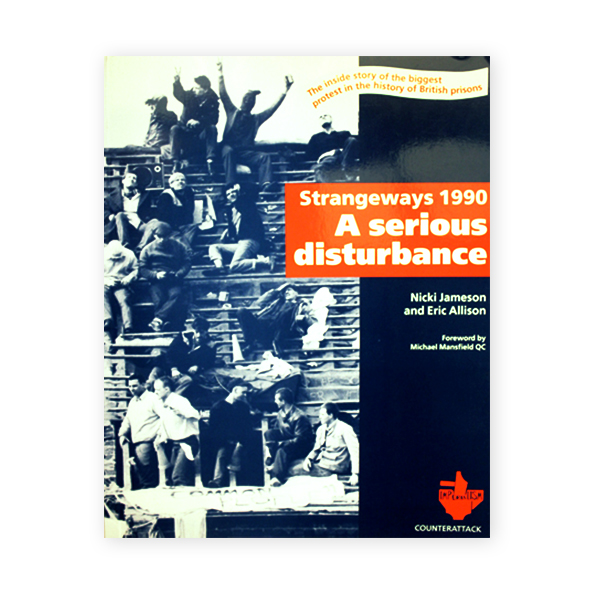

Strangeways 1990: A Serious Disturbance (digital book)

The inside story of the biggest protest in the history of the British prison system, told through the eyewitness accounts of prisoners and ex-prisoners, their families and supporters.