In some ways the British police haven’t changed a bit. In a review of the findings of the Policy Studies Institute report, Police and People in London, in November 1983, The Economist wrote: `Under his peculiar Victorian Helmet, your ordinary London bobby is racist, sexist, bored, aimless and quite often drunk.’ Fourteen years later, the police force still pretends to be concerned about the racism and sexism which, it openly admits, festers in its ranks: it just fails to do anything about it. What has changed are the powers which these bigots possess in law. For, since 1981, the British state has systematically transformed the police in one respect they are now organised and equipped both legally and in paramilitary terms to deal with political dissent by overwhelming force. On the receiving end of this transformation has been a generation of workers, black people and political activists — in 1984-5 it was the striking miners and the Broadwater Farm Estate, today it is road and environmental protesters. The British state is tooling up and honing its powers for future confrontations with the working class and its allies. CAROL BRICKLEY reports.

In the February/March issue of FRFI (135) we reprinted an article from 1983 which described the beginning of this transformation process: from the fiction of ‘policing by consent’ using `minimum force’, to the reality of para-military policing. A shattering series of uprisings in Britain’s inner cities in the Spring and Summer of 1981 were the catalyst. In Brixton and Toxteth the police almost lost control faced by the determined outrage of local people at police racism. By September 1981, Kenneth Newman had moved from the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) to Metropolitan Police Commissioner. The Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) — an unregulated, non-statutory body of Chief Constables and Deputies — organised an emergency session on Public Order Policing at its annual, secret conference.

Three forces addressed the emergency session: the Met Police, the RUC, and the Royal Hong Kong Police (RHKP). Two of these, the RUC and the RHKP, were expert at suppressing sections of the local population by force, using methods refined in British colonies the world over.

The keynote speech was delivered by Richard Quine, Director of Operations for the RHKP. The attraction for ACPO was the RHKP’s experience as a paramilitary force organised to sup-press rebellion and trade union activity in the colony. Hong Kong was not a democracy until it became convenient for the British in the run-up to the 1997 Chinese take-over. Its people were ruled as a subject people and the RHKP riot squad was the force trained to keep them in subjection. The plastic bullet was developed from the ‘bamboo baton round’, a favourite RHKP weapon.

From this conference, with the sup-port of the Home Office, ACPO organised a full review of public order policing. This resulted in the formation of the Public Order Forward Planning Unit to co-ordinate policing on a national basis, and the production of the secret ACPO Public Order and Tactical Options Manual, cataloguing repressive organisation and restraint techniques. These techniques were designed, in the words of the Met’s magazine The Job, to give the impression of ‘visual non-violence’. Brigadier Mike Harvey, a Korean war veteran who developed arrest and restraint methods in the north of Ireland was brought in to train the Met police.

In short, there had been a radical change in policing methods in Britain, without the slightest reference to any democratic process. Gerry Northam sums it up in his book Shooting in the Dark:

ACPO has taken great care to shroud its new policy in secrecy. It is difficult to see this as a sign of faith in public support. It suggests, to the contrary, that a profound shift in thinking has taken place among some senior police officers which leads them to treat parts of Britain like colonies. Tactics which were previously reserved for use against subject peoples overseas, are now considered appropriate for the control of British citizens at home. Whether or not it was ever morally right to employ them for foreign suppression, the decision to import these tactics into domestic policing is of the greatest political significance. ACPO has decided in secret that part of Britain’s population should be treated, on occasion, like hostile aliens. Can they avoid the conclusion that, for some purposes, it is no longer their intention to police by consent.’ (p139)

No one should be surprised at this ‘shift’. The police force and the law has always been used against political dissent. Special Branch was formed in the 19th century to combat Fenian bombings in London and to co-ordinate police work on Ireland. The 1936 Public Order Act, purported to be in opposition to the British Union of Fascists (BUF), was first used against striking miners in Nottinghamshire. It was hardly ever used against the fascists, even when the stewards at one BUF meeting threw an opponent out of the doors, face down on to stone steps, in full view of the police. ‘Policing by consent’ is the creature of more quiescent periods. Nonetheless, the decision to adopt paramilitary policing methods in 1981 represented the recognition by the ruling class that the post-war boom had ended: class confrontation was now on the agenda again.

ACPO’s strategy was undoubtedly promoted by its political masters — the Thatcher government. The Tories knew that the direct result of their plans in favour of finance capital and the free market would be confrontation. A paramilitary policing strategy would be necessary to deal with ‘the enemy in our midst’. That enemy was the working class: on the one hand, the dispossessed inner city youth, denied opportunity, choked by discrimination and on the receiving end of police racism; on the other hand, the industrial workers, soon to be dispossessed themselves, when Thatcher’s government destroyed British manufacturing industry, throwing millions on to the dole.

Newman, in his first annual report as Met Commissioner, targeted inner city London communities — predominantly black — as in need of ‘special’ policing. He put London ‘on notice’ to expect police violence directed at ‘alienated’ communities. But it was in 1984/5 that Britain’s new paramilitary police were to be really tested — during the Miners’ Strike and on Broadwater Farm Estate in London.

The Miners’ Strike was the big test of the new strategy. The police were organised nationally to block motor-ways and roads to halt free movement of strikers and their supporters; whole mining communities were isolated, held under siege and harassed; massed riot squads were marshalled at pit-heads to attack the pickets, snatch individuals, intimidate, brutalise and criminalise the strikers. The lackey media launched a campaign of vilification — lying about the violence of the strikers, promoting the strike breakers and the police. At Orgreave, television footage was reversed to give the impression that the massed ranks of riot police were simply defending themselves from attack by the pickets — the complete opposite of the truth. Indeed it was not until the Orgreave riot trial in July 1985 that the existence of the Tactical Options Manual was leaked. It was only after this that ex-tracts were placed in the House of Commons Library — the first that Parliament knew about it.

The Newman/Kitson (see FRFI 135) strategy to eliminate dissent was followed to the letter: first, isolate the dissidents; second, recruit the moderates to support the State/Police; third, crush the opposition with force — the riot squad and courts. To do this they used intelligence gathering (eg, surveillance, bugging, spying) and ‘psychological operations’ (disinformation and dirty tricks) to confuse and discredit the opposition. That is why the media accused miners’ leader Scargill of corruption. The Labour Party and trade union leadership were willing helpers in the campaign: Kinnock and Willis teamed up to attack the strikers for violence and to block vital support. They were silent on the radical change in policing used to crush the strike.

Broadwater Farm Estate in the Autumn of 1985 was to provide the second opportunity to test the new tac-tics. Within a short time of the out-break of anger following the death of a local woman, Mrs Jarrett, during a police raid, thousands of police were mobilised into riot squads. Residents were held under siege for weeks after the event, flats were raided and snatch squads picked up black youths. Selective leaks to the press recruited public support for the police action, ensuring that those arrested would not get a fair trial. Juveniles were brutally treated under interrogation and the police got away with it. The men accused of the murder of PC Blakelock were found guilty simply because the state had created a ‘hue and cry’ against them and the police manufactured the evidence. Winston Silcott still rots in gaol as a result. Once again the Labour Party joined in solely on the side of the State and its police.

With two major experiences under its belt, the legislative arm of the State — Parliament — introduced laws which made use of the lessons the police had learned. The Police and Criminal Evidence Act (1984) and the Public Order Act (1986) extended police powers both in respect of arrest and in relation to political demonstrations. Marches now had to be notified to the police seven days in advance; the police could determine the route and place conditions on the marchers. Conditions were also placed on ‘static assemblies’ of more than 20 people. Very quickly peaceful demonstrators were subject to police violence — copy-book restraint techniques from the Tactical Options Manual.

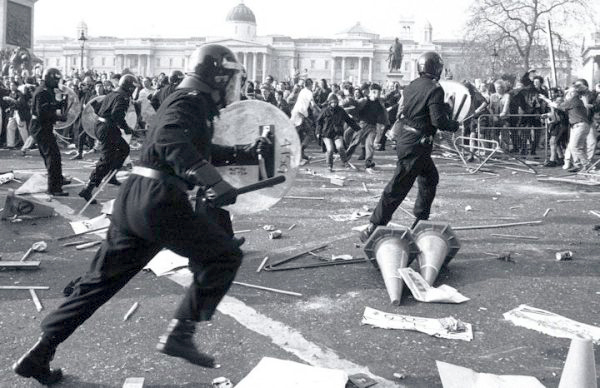

The next major confrontation — the Poll Tax demonstration of March 1990 — followed the familiar pattern of Riot Squad deployment, press witch-hunts of protesters, surveillance, manufactured evidence and disinformation by the police, harsh sentences in the courts (called for by Labour leaders), and the, by now, ritual Labour Party denunciation of all violence except police violence.

Perhaps the laws and the riot police were enough to deal with the clashes of the 1980s. But the State is continually revising its plans for dealing with opposition, the more so since it expects dissent to deepen and widen. The recent tranche of legislation is not just the product of the depraved imaginations of Tory MPs. Viewed as a whole, it is a systematic escalation of police powers in order to deal with the crisis to come.

The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 — hailed as progressive for its reduction in the age of consent for homosexuals — in fact targets young people, their culture and their political activities for ‘special policing’. Ravers, squatters, environmental protesters, hunt saboteurs are all criminalised. The Act also removed the right to silence and further restricted the right to peaceful assembly.

The Security Services Act 1996 and the more recent Police Act (which is awaiting completion virtually unamended by the new Labour Government) have introduced fresh powers of surveillance, bugging, and breaking and entering without judicial warrant. Communities may welcome the use of closed circuit television cameras (CCTV) on the grounds that it prevents crime, but CCTV has a far more important part in the strategy of the state to prevent and crush opposition. Surveillance does not stop there: government departments can now share the information they hold about individuals, and employers can demand to see employees’ criminal records.

These laws are ostensibly for use to combat ‘serious crime’, but the definition of ‘serious crime’ includes ‘con-duct by a large number of persons in pursuit of a common purpose’. This is the old conspiracy law. It is not in-tended for use against the massed ranks of the ruling class heading for Ascot; it is the catch-all law for crushing working class opposition to the State.

Intrinsic to the paramilitarisation of the police and the laws that go with it, is the constant blurring of any demarcation between criminal activity and political dissent. The Tactical Options Manual continually and deliberately uses the terms criminal and protester interchangeably. Political activity out-side and beyond the corrupt activities of Parliament (treated as criminal) is being criminalised.

Reclaim the Streets has been subject to repeated raids, surveillance and confiscation of their computer disks. Small demonstrations, called at short notice, are now attended by police in riot gear. 20,000 copies of Evading Standards — a mock edition of the Evening Standard — produced on the eve of the March for Social Justice in April, were confiscated by police who were waiting at the delivery point. Road campaigners are spied on — the £2.2 million that the Department of Transport have been paying a detective agency to spy on activists will be saved now that the police can do the job. The Forward Intelligence Unit — part of the Public Order Unit at the Met — can hardly wait to test its old and new powers: ‘if a particular environmental cause were to spread countrywide, then mutual aid on a scale not seen since the miners’ dispute might once again be required.’ (Chief Superintendent Davies, Police Review 21 March 1997).

CS gas is in general use against hunt saboteurs and even against working class mothers trying to stop their children being taken into care. The police are armed to the teeth with long batons and guns for use against their old enemy — the now even more alienated inner city youth — especially if they are black. A few ‘liberal’ Chief Constables may be shocked that fellows are so bigoted, but the majority know that it is an essential feature of policing the crisis. We have no illusions that Labour will change this — their only loyalty is to the British State and their own class. Our job is to build united opposition to the hired liars in the media, the opportunists in government and the thugs who police political opposition on their behalf.

FIGHT RACISM! FIGHT IMPERIALISM! AUGUST/SEPTEMBER 1997