1 April 1990 saw the start of the biggest uprising the British prison system has ever seen. Coming the day after the massive London anti-Poll Tax demonstration, the revolt started in the chapel of Strangeways prison in Manchester, in protest against oppressive prison conditions and thuggish behaviour by prison officers. From there, it spread, first through the whole of the prison, which the staff rapidly abandoned, leaving the prisoners in control, and then across the whole system, as gaol after gaol joined the uprising. NICKI JAMESON reports on the 30th anniversary of the Strangeways protest.

Although the prison population has nearly doubled since 1990, even then Britain already had the highest per capita imprisonment figures in Western Europe, and conditions were squalid and insanitary. Many prisons were over a hundred years old and almost none had toilets in the cells. Instead, prisoners – often held three for a cell built for two for up to 23 hours a day – would urinate and excrete in buckets and ‘slop out’ each morning. And on top of the appalling physical conditions, staff brutality was rife, as was drugging with largactyl, known as the ‘liquid cosh’.

The protest began when prisoner Paul Taylor marched to the front of the church service, grabbed the microphone from the prison chaplain and began talking about all the injustices prisoners faced. This was a pre-arranged signal for general uproar and what had originally been planned as a protest within the chapel; however, when the staff fled, prisoners moved from the chapel to the prison roof via some convenient scaffolding, and from there took over the whole prison.

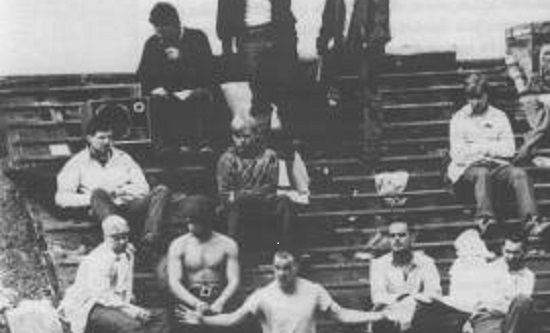

While the vast majority of prisoners stayed only a few days, a core group hung on to the end, with the final five leaving the roof in a cherry-picker on 25 April to tumultuous applause to the families, friends, activists and well-wishers gathered below. For the duration of the siege, they had communicated with those offering solidarity and with the media via placards and banners putting across their grievances, and had also tried to negotiate with Prison Service spokespeople, though to little avail.

During the 25 days of the Strangeways uprising, there were other protests across the prison system, including at Dartmoor, Bristol, Cardiff, Gartree, Swansea, Hull, Winchester, Wandsworth and Shotts in Scotland.

Such was the visibility of the uprising that the Conservative government, then headed by Margaret Thatcher, was forced to commission an inquiry, led by Lord Woolf, not just into the revolt, but into the terrible prison conditions which had brought it about. At the same time, the authorities moved to punish the very prisoners who had blown the whistle and let everyone see how bad things were inside the nation’s gaols. At a series of trials, the ‘ringleaders’ and some others were punished with sentences of up to ten years on top of those they were already serving.

The Revolutionary Communist Group consistently supported the Strangeways prisoners and all those around the country taking action against brutal conditions and treatment. We covered the uprising and its aftermath in our newspaper and we produced the only non-academic book written about the protest: Strangeways 1990: a serious disturbance.

Strangeways 1990: A Serious Disturbance (digital book)

The inside story of the biggest protest in the history of the British prison system, told through the eyewitness accounts of prisoners and ex-prisoners, their families and supporters.