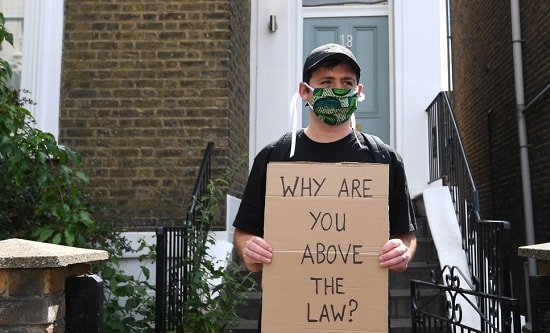

As of 15 May, 18,000 fine notices had been issued under the Coronavirus Health Protection Regulations, which provide the legal framework for the lockdown. On the same day, the Crown Prosecution Service announced that all of the 44 arrests which had been made under the Coronavirus Act 2020, a separate piece of legislation to the Regulations, were unlawful. The power under the Act relates specifically to people who appear to have the virus, but the police had used it to arrest people who they claimed were breaching the Health Protection Regulations by being out of their house for a non-specified purpose. On 22 May it emerged that Boris Johnson’s right-hand adviser Dominic Cummings had breached the Regulations; he has not been fined. NICKI JAMESON reports.

Britain has been in a state of ‘lockdown’ since 23 March, although this has not at any stage been nearly as rigorous as in many countries. Despite the government already having sufficient legislation in place with which to lock down the country, as the Public Order Act, Anti-Social Behaviour Act and Civil Contingencies Act (the last the legacy of the Blair government) gave it all the power it needed, since 10 February it has introduced several new laws, which add to this armoury.

On that day the first Coronavirus Regulations came into force, introducing the power to detain people for the purpose of screening for the virus. This was followed by the Coronavirus Act 2020, which came into force on 25 March, and which repeated the power to detain a person suspected of having coronavirus, in order to forcibly test them. Ironically, this became law at a time when the government was essentially refusing to test anyone, even those begging for a test. The Act also contains a wide-range of provisions, including suspending jury involvement in inquests and allowing police forces to hold DNA and fingerprints indefinitely.

Most significant to the lockdown, and also on 25 March, the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020 (SI 350) became law. They have been amended several times since – in particular following the ‘Stay Alert’ turn announced by Boris Johnson on 10 May, to allow for people to meet ‘one person outside their family’, and then again following further relaxations announced on 28 May – but the core powers remain the same.

The key provisions are:

Regulation 6, which states ‘During the emergency period, no person may leave or be outside of the place where they are living without reasonable excuse.’ This is then followed by a longish list of things which constitute a ‘reasonable excuse’, including basic shopping, exercise, caring for vulnerable people and ‘to travel for the purposes of work or to provide voluntary or charitable services, where it is not reasonably possible for that person to work, or to provide those services, from the place where they are living’. As the lockdown loosens and the government emphasis is on ‘return to work’, in particular for those who are on furlough and therefore costing the government money, the list of permissible activities will get longer.

Regulation 7, which bans gatherings of two or more people not in the same household, for any purpose other than attending a funeral, moving house, providing care or assistance to a vulnerable person, providing emergency assistance and participating in legal proceedings or ‘where the gathering is essential for work purposes’.

Contravening the Regulations can result in a fine. The standard penalty was initially £60, and has now been increased to £100, rising for each subsequent offence, with a potential fine of £3,200 for someone who has breached the Regulations on six occasions. The Coronavirus Act is in force initially for two years and the Regulations for six months. The largest number of fines, as of 15 May, had been issued by the Metropolitan Police (906), with Thames Valley issuing 866, North Yorkshire 843 and Devon and Cornwall 799. In contrast Gwent police issued only 71, Staffordshire 52 and Warwickshire Police 31.

In addition to the legislation, there is a plethora of ‘guidance’ on how to implement the Regulations and what is and isn’t a breach, issued by the government itself, by different police forces and by the College of Policing. Unsurprisingly, many police officers charged with implementing all this have no idea what they are doing and instead simply fall back on their own prejudices. Research by Liberty and The Guardian published on 26 May confirmed that Black, Asian and minority ethnic people in England are 54% more likely to be fined than white people. Video of an incident in Manchester on 6 May, during which police tasered a black motorist in front of his young son, went viral; Desmond Mombeyarara was subsequently charged with driving offences and ‘unnecessary travel’ under the Regulations.

In stark contrast to the treatment of Mombeyarara, Durham Police announced on 28 May that although it accepted that the Prime Minister’s special adviser Dominic Cummings had committed ‘a minor breach relating to lockdown rules’, it would not be taking any action against him, and had they caught him at the time ‘the officer would have spoken to him, and, having established the facts, likely advised Mr Cummings to return to the address in Durham, providing advice on the dangers of travelling during the pandemic crisis’. The police only appear to have considered the Health Protection Regulations and did not address the question of whether Cummings should have been arrested under the Coronavirus Act. Unlike all the people wrongly prosecuted under the Act, he actually did travel at a time when both he and his wife considered themselves to have symptoms of Covid-19, so it may well have been applicable.

Cummings had driven from London to his parents’ farm in Durham on 27 March, returning two weeks later. Although he initially claimed not to have left the farm during that period, he was subsequently compelled to admit to two further journeys, most notably on 12 April (his wife’s birthday) to the town of Barnard Castle. Despite his bizarre justification for the trip (checking if his eyesight was up to driving back to London), and indeed his far from credible rationale for the whole journey, Cummings has not only not been charged, but has been entirely exonerated of any wrongdoing by the same Prime Minister and Cabinet, who told us emphatically, at the very time that Cummings was in Durham, that staying at home was ‘an instruction, not a request’. In the daily parliamentary briefing on 26 May, Health Minister Matt Hancock was asked whether, following the exoneration of Cummings, there would be a review of fines issued during lockdown to ensure that nobody else had been penalised for similar actions. Hancock was temporarily wrong-footed but within an hour, the government had made it clear there would be no review.

Despite the overt bias as to who gets punished for breaching the rules, the lockdown has, in the main, been policed by consent, as the majority of the public consider the overall aim to be correct; however what comes next, as we move out of lockdown, may not be so generally welcomed. A massive recession is on the horizon, in which the ruling class will seek to recoup the money it has lost during the pandemic. We are going to need to organise in the coming period to defend our homes, jobs and communities, and we will need to be prepared to fight against laws introduced under the auspices of protecting us being retained in order to repress us.