FRFI 207 February / March 2009

The new Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir Paul Stephenson was appointed on 28 January promising to ‘convince all the communities of London that the Met is on their side’. His appointment followed the resignation of Sir Ian Blair in November 2008, who left under several looming clouds, not least the imminent verdict of the Jean Charles de Menezes inquest; allegations of racism from senior Asian police colleagues and a boycott by the Metropolitan Black Police Association; and an investigation into personal corruption.

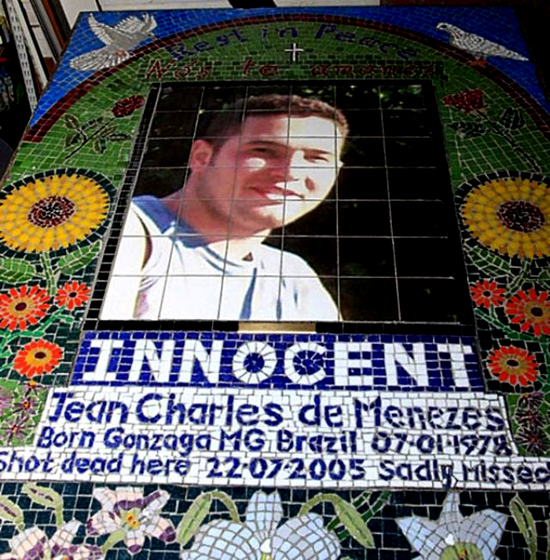

The open verdict in the De Menezes inquest, which ended in December, proved to be the indictment of policing that Sir Ian Blair had feared. The jury were prevented from bringing a verdict of unlawful killing by a ruling of the coroner, but went as far as they could to point to the culpability of the police. The De Menezes family welcomed the verdict as at least some recognition of the circumstances of their son’s killing in Stockwell on 22 July 2005. But the family did not receive justice and they stand in a long line of families who have been on the receiving end of the development of police tactics to deal with political opponents, tactics which include murder and brutality.

Despite the new Commissioner’s stated hopes, the Metropolitan Police is not a ‘service’, it is a force which operates on behalf of the British state and cannot possibly be on the side of all communities. In the last 40 years, two issues have been the catalysts for fundamental reviews of how the police force operates. First was the renewed nationalist struggle in Ireland from the late 1960s onwards. Second was the outbreak of inner city uprisings from the early 1980s onwards. Before this the British police and British Army – twin agents of British rule – pursued different methods. Abroad the British state developed specialist repressive tactics to deal with opposition. In Britain it was ‘policing by consent’, with occasional exceptions if the working class fought back. For the most part, Britain’s imperialist exploits ensured civil peace at home at the expense of the oppressed nations in the British Empire.

The outbreak of the ‘Troubles’ in the north of Ireland brought the struggle against imperialist rule to Britain’s doorstep, and to mainland cities. During the 1970s new tactics were developed to deal with this opposition to British rule. In particular, Sir Kenneth Newman, Chief Constable, Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), and Brigadier General Frank Kitson, British Army, were at the forefront of adapting the methods of colonial policing to deal with the Republican movement.

The first inner city uprisings in Britain in 1981, at Brixton in London and Toxteth in Liverpool, severely tested the police who tried to crush the black and white youth on the streets. The police only narrowly held their ground despite the lack of any real organised fightback. When order was restored, Newman, now Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, ensured that the lessons of the Irish struggle were adapted for use against any section of the British population that challenged the British state. In Britain increased police powers were used against the striking miners (1984-5) and against the black community in Broadwater Farm (1985).

Shoot to kill in Ireland

It was in Ireland that the shoot-to-kill policy, operated by the RUC and the British Army, first emerged. For many years the nationalist people in the north had believed that individual Republican activists had been targeted and killed by British forces, but in 1982, within a one month period, six men were shot dead by the RUC. All six shootings followed a similar pattern. The men were unarmed and were shot by members of the RUC E4A unit, an SAS-trained squad. E4A was effectively a heavily-armed, covert police murder squad organised on military lines, operating from unmarked cars. After each killing the RUC issued a false cover story, removed witnesses and destroyed forensic evidence. A forged RUC report was compiled on one man after his death (he had no Republican connections) in order to implicate him.

Five years later, in 1988, the British Attorney General closed all inquiries into the events of 1982, regretting that there was some evidence of police corruption but because of ‘considerations of national security’ no charges would be brought against the officers involved in the killings or the subsequent conspiracy to obstruct justice.

Two months later, an IRA active service unit was gunned down on the streets of Gibraltar. Despite British claims, and press reports describing the ‘bomb’, there was no remote-controlled bomb, and the victims were unarmed. The SAS killers claimed that their victims made aggressive movements before being riddled with bullets. The subsequent inquest was rigged and independent witnesses were intimidated and slandered. The similarities between the 1982 killings and the events in Gibraltar are striking.* And the British government got away with it again.

The killing of Harry Stanley

Armed response units and Specialist Firearms Officers (SFOs) were introduced on the streets of London in 1991. This represented a culmination of the changes begun by Newman in 1982. No more policing by consent. Police powers to deal with political demonstrations and militant strikers like the miners were dramatically enhanced. The Prevention of Terrorism Act became a permanent fixture in British law, as civil rights were diminished to make way for policing ‘the enemy within’.

On 22 September 1999, Glaswegian Harry Stanley was gunned down in the street near his home in Hackney by two SFOs. They claimed they had been tipped off that an Irishman was walking the streets with a sawn-off shotgun. Harry Stanley was carrying a repaired table leg in a plastic bag. The SFOs claimed that they had shouted warnings for him to stop but Stanley made an agressive movement pointing ‘the gun’ in their direction, so, to defend themselves, they shot him. Stanley had no political connections and was entirely innocent. Well, you might say, we all make mistakes, don’t we, but that is not the end of the Harry Stanley story.

In the days following the killing, Stanley’s family were subject to grilling by the Metropolitan Police, trying to convince them that Harry’s mood was suicidal and to suggest that he may have set out to get shot. Harry’s son described the police as ‘the gestapo’. At the first inquest in 2002 the coroner ruled out unlawful killing as a verdict, and admitted into evidence Harry Stanley’s criminal record, despite its irrelevance since the SFOs did not know who they had shot. The evidence of the two officers was strikingly similar due to the fact that they were allowed to compile their statements together. This is stil normal procedure for shooting incidents. They claimed that Harry was facing them when he was shot. The jury, unconvinced, returned an open verdict.

As a result of further forensic evidence showing that Harry was shot in the back of the head, a second inquest was called which ended with a verdict of unlawful killing. The two SFOs then began a public campaign to avoid being put on trial for manslaughter or murder, enlisting the aid of the press to advertise the trauma they and their families were suffering. With the help of further ‘expert evidence’ they were able to successfully judicially review and quash the second inquest verdict. The new ‘expert evidence’ came from a US professor who claimed that people who are being shot can move very quickly and that police who shoot them often get the facts wrong due to trauma.

In the end, six years after the killing, all the criminal and disciplinary charges against the SFOs were dropped. The Stanley family did not get any justice at all. Neatly, from now on at such inquests, forensic evidence which runs counter to police evidence could be discounted.

These were the lengths the police were willing to go to in 2005 to justify shooting an entirely innocent man. They were prepared to go further.

Anti-terror policing

The attacks on London Transport passengers on 7 July 2005 which killed 52 people and the later, failed, attacks on 21 July, once again changed the nature of policing in London. As a result of bombings in other cities, in particular Madrid in March 2004, the police developed a new strategy for dealing with suicide bombers, called KRATOS. This is essentially a procedure for killing identified suicide bombers without warning.

Just as the Irish community in Britain found itself targeted indiscriminately in response to the IRA’s campaign, and just as the black community in Broadwater Farm was held under police siege in 1985, the Muslim community soon found that they were to be the next to suffer. Massive increases in stop-and-search of any young men ‘looking like Muslims’ and raids on premises in Muslim areas were justified on the grounds that ‘being Muslim’ means you may be guilty.

At 4am on 2 June 2006 the Met police raided two houses in Forest Gate, East London. They claimed to have ‘intelligence’ that the houses were being used to manufacture a ‘dirty bomb’. The raid involved armed officers wearing full biological protection outfits, including masks and breathing apparatus, carrying torches. In the course of the raid, one man was shot and another wounded on the head. Both said they were terrified by the raid and did not realise it was the police. The victim of the shooting and his brother, after medical treatment, were arrested and taken to Paddington Green Police Station where they were held for seven days, after which they were released without charge. Nine other people, including a baby, were taken to Plaistow police station, where, although not under arrest, they were held in the police canteen and ‘persuaded’ to give DNA samples and finger prints, with no access to solicitors.

No ‘dirty bomb’ was found. None of the complaints against the police were upheld in the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) inquiry and no criminal charges brought. The shooting was held to be an accident on a dark landing. The head injury was in line with the police strategy of ‘dominating by aggressive behaviour causing fear’. The officer concerned said he had struck the man?because he did not obey instructions and ‘he was reaching under his bed for something’. Most of the police officers could not be identified because of their protective outfits, so most of the complaints went no further.

It is now lawful, on the basis of undisclosed ‘intelligence’, for large numbers of police to raid your home in the middle of the night, treat you extremely aggressively and violently, and if they deem it necessary, or you try to protect yourself and your family, they can assault you or shoot you. You will have no redress.

The killing of Jean Charles de Menezes

The facts of the shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes on 22 July 2005, the attempted cover-up, failed investigations, and decision not to charge or discipline any of the Met Police officers involved, show how far the British state will go to defend itself. De Menezes was shot in full view of passengers having been ‘identified’ as one of the failed bombers from the day before. The police only had a vague idea of what their target looked like, but on the basis of their racist descriptions of the man who left a block of flats in Tulse Hill, caught two buses and entered the tube at Stockwell station, they had no hesitation about pumping seven dum dum bullets into his brain.

The immediate response of the police was to cover-up their mistake. Within hours press reports appeared describing De Menezes as wearing bulky clothing, behaving nervously, jumping the barriers into the station. De Menezes was wearing light clothing, carrying nothing and did not jump the barriers. Police press statements from Scotland Yard claimed that he had emerged from a known terrorist house – not a block of flats – and that he had failed to respond to police warnings. Once it was known that Jean Charles was an innocent Brazilian, news was spread that he was an illegal immigrant, and later that he was a suspected rapist – as if this might justify his treatment. At Scotland Yard, lying press releases were being issued and the police were holding back the information that they had shot an innocent man. The Commissioner even claimed that he did not know this until the following day. Sir Ian Blair tried to block the investigation by the IPCC, but he needn’t have bothered as the IPCC already had a deserved reputation for dismissing complaints against the police.

Readers will recognise the pattern of police behaviour and cover-up which was manifest in Ireland’s shoot-to-kill cases, the Gibraltar three and at Harry Stanley’s inquests: lie about the events surrounding the shootings and then blame the victim. The IPCC duly found that individual police were not to blame. A charge of breaching health and safety laws was brought against the Metropolitan Police, for which they were fined. The inquest jury did its best and rejected the police evidence, but they may be the last jury able to do so. The Labour government is now preparing legislation to ensure that future inquests in cases involving national security or sensitive intelligence will be held in private without a jury. This will seal the whole system and ensure that the police can get away with murder with no questions asked.

Jane Bennett

* Many of the events cited in this article have been the subject of articles in FRFI or in books and pamphlets written over the last 30 years. Most of these are available on the RCG website, including Murder on the Rock, an analysis of shoot to kill and the Gibraltar Three. I gratefully acknowledge this work. See here

For the de Menezes family campaign, see: justice4jean.org