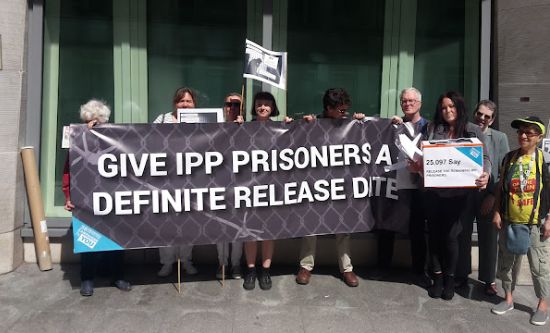

In September 2021 the parliamentary Justice Committee launched its inquiry into the continuing legacy of the Indeterminate Sentence for Public Protection (IPP). The sentence was supposedly abolished in 2012; however, 1,700 IPP prisoners remain imprisoned indefinitely, many having been paroled and then returned to prison for minor breaches of licence. Former life-sentence prisoner JOHN BOWDEN reports.

The agenda of the Committee’s inquiry is to explore possible changes in legislation or policy to reduce the number of IPP prisoners, although under a government and state determined to wield the prison system as a weapon of more repressive social control and mass incarceration, it is unlikely that any recommendations the Committee does make, even for a minimal reduction in IPP numbers, will translate into reality.

The IPP was introduced in 2003 and came into force in 2005. It was part of the ‘tough on crime’ agenda of the right-wing Labour government of Tony Blair. That agenda, of course, didn’t include being tough on corporate or war crime, both of which Blair was implicitly involved in. And, as usual, it sought to replicate the most repressive examples of the US ‘justice’ system, specifically the ‘three strikes’ law or mandatory sentencing, where the legislature, not the judiciary, decides on prison sentence lengths. The ‘three strikes’ law specifically targeted ‘repeat offenders’ in poor, black communities, resulting in the mass incarceration of young black men for relatively minor offences, such as petty theft, who would then remain imprisoned for decades.

Labour Home Secretary David Blunkett claimed that in England and Wales the IPP would specifically target violent and sexual repeat offenders, who posed a serious danger to the public, and predicted that about 900 people would be imprisoned under the law. In fact, between 2005 and 2012, 9,000 were imprisoned, some for relatively minor robbery offences. This massively increased Britain’s population of life and indeterminate sentenced prisoners, already the highest in Europe.

As with all life or indeterminate sentenced prisoners, whilst the judiciary can set the minimum term, or tariff, for which they should be held, it is the Parole Board which ultimately decides if the prisoner should ever be released, and whilst most IPP prisoners convicted for minor offences were originally sentence to short tariffs – in some cases 28 days to six months – many remained in prison for more than ten years, some even longer. Those who did eventually achieve release remain on strict parole licence, subject to recall to prison for a further indefinite period for minor breaches of their licence conditions.

In 2012 the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the British government had breached Article 5 of the Convention on Human Rights in its treatment of IPPs. Shortly after this the IPP law was supposedly abolished. However, this abolition was not retrospective, meaning that 1,700 prisoners are currently incarcerated under a law which officially no longer exists.

In terms of why so many IPP prisoners remain imprisoned long beyond their original tariffs, the role of prison-hired psychologists is a crucial one. Over at least the last two decades the power of prison psychologists in determining the release or not of indeterminate sentenced prisoners has increased massively and, as a consequence, most life sentence prisoners now spend years and decades in prison beyond the original tariffs imposed by the courts. An absolute prerequisite of release on parole for all long-term prisoners now is their willingness to engage with psychology-based programmes to address their ‘offending behaviour’. Those who refuse to cooperate with such courses are labelled as suffering with ‘oppositional defiant disorder’ or ‘anti-social personality disorder’, and inevitably denied parole. Because of the mass overcrowding of prisons and limited access to such courses, even those life sentenced prisoners who agree to participate in order to try and achieve release often spend years waiting to be granted a place on them.

The role of the Parole Board, an almost exclusively white and middle class body, in maintaining the imprisonment of IPP prisoners and creating a massive congestion of post-tariff lifers generally is ultimately the cause of why so many IPP prisoners continue to languish in prison. In the eyes of Parole Boards, what actually determines suitability for release isn’t minimum risk to the community but absolute submission to prison power and authority.. This is certainly proven by controversial Parole Board decisions to release those convicted, for example, of multiple rape, but who have met the criteria of ‘model prisoner’, on the expiry of their minimum tariffs, whilst repeatedly denying the release of prisoners who question and challenge prison authority, despite – as in the case of those IPP prisoners originally imprisoned for relatively minor offences – their representing absolutely no risk to the public.

According to the Prison Reform Trust, between January 2015 and September 2019, 1,760 IPP prisoners were recalled to prison, many of them on more than one occasion, amounting to 2,342 recalls in total. This shocking number of recalls – most of which are not for breaking the law but for minor breaches of parole licence – reflects the mentality of a probation service, which is co-joined with the prison system and sharing its carceral function. Ostensibly, the probation service was set up to assist and support released prisoners to resettle and reintegrate into society, but in fact the true purpose of probation officers is to police the behaviour and attitude of released prisoners on parole and extend the power of prisons into the community, especially poor disadvantaged communities. Life sentence and IPP prisoners who are finally released on parole are for the remainder of their lives subject and vulnerable to the arbitrary power of probation officers, and as the enormous number of IPP prisoners returned to prison whilst innocent of any crime shows, probation officers are absolutely complicit in maintaining a system of unlawful imprisonment.

Whatever comes out of the Justice Committee inquiry, the growth of the prison industrial complex in Britain and the increasing criminalisation of the poor and disadvantaged does not bode well for those who remain imprisoned under IPP law, whose only real hope of liberation lies in the struggle to overthrow the entire apparatus of capitalist state repression.