Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! No. 83 – January 1989

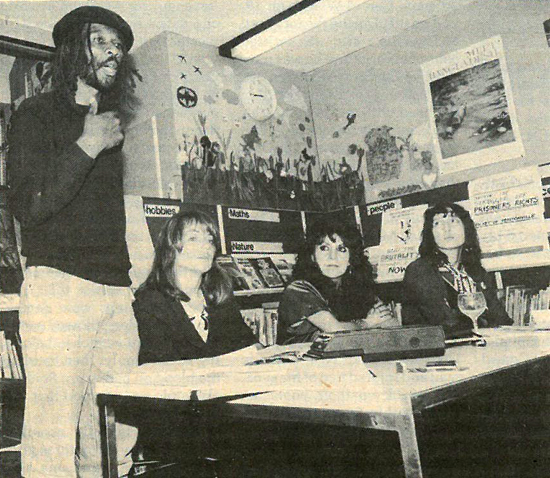

Shujaa Moshesh (previously Wesley Dick) was released from prison in August 1988 after serving thirteen years. He was arrested, with two others, in the Spaghetti House siege of 1975. Before his arrest he was a political activist in the black community and it was the political character of the Spaghetti House siege that led to heavy sentences against those involved. Inside prison Shujaa was a well-known fighter for the rights of prisoners and played a leading role in numerous strikes and protests. For this he was victimised and lost most of his remission. Terry O’Halloran and Maxine Williams interviewed him shortly after his release.

Could you tell us about your experiences as a black prisoner? How the racism of the system operated?

You have to bear in mind that I was arrested for opposing the state although of course they criminalised us. But basically we were fighting racism outside and when we were arrested and put in prison it was just a continuation of that struggle.

Racism in prison is far more intense than it is on the streets. Right from the word go we were confronted with racist practices by the screws and the governors. Some things sound petty but they affect the life of the prisoner involved. For example when you’re going up for dinner you’ll see a white prisoner get two eggs and a black prisoner get one. Or recently when John Alexander, a prisoner in Parkhurst took the Home Office to court about working in the kitchen. I was in prison for thirteen years but I only ever saw two black prisoners working in the kitchen, one was in Hull, one in Blundestone. Not that I want to work in any kitchen anyway but if people want to work in a kitchen they shouldn’t be discriminated against on the grounds of colour.

Some prisons are known to be more racist than others, Wandsworth and Strangeways. In the local prisons where prisoners aren’t supposed to be doing sentences or only short term, the racism is more intense than in the dispersals. Because black prisoners are going to be in the dispersals for some time the screws don’t want too much hassle; they know that if there’s racism in the prisons, black prisoners will resist it.

Black prisoners suffer more from practices like ‘nutting off’ (sending prisoners to mental hospital)?

Prison doctors’ and prison staff views fit in with the general theory of how society’s rulers see people. They put it in the framework of white men are middle class. They want prisoners to fit into this image. So if they have a black man in there from Jamaica or West Indies, or Africa, who doesn’t talk what they see as good English, they question his educational abilities. If he is putting up some kind of resistance to the racism he is in great danger of being nutted off. It nearly happened to me. I can think of several guys who’ve been sent to Broadmoor or Rampton.

During the trial of Jimmy McCaig and John Bowden there was a psychiatric report given on McCaig and one phrase stuck in the mind. The psychiatrist said he had an ‘overdeveloped sense of justice’.

I regret that I only got a glimpse of the report on me. They say all kind of things. I remember one prisoner I know was called ‘evil, ignorant and an absolute degenerate’ by a screw who had known this prisoner for about three days. That statement alone could keep a man in prison. It’s not what is said that is the point but the power that lies behind those words especially if you’re a lifer. They can leave you in there literally for life. If prison officers don’t like your resistance, they can write all kinds of things about you in a report which is going in front of governors and parole officers.

Do the authorities see black prisoners as a threat because they are organised?

It’s not all black prisoners who are organising just as it’s not all white prisoners who are not organising. Generally you can say that the average black prisoner is more politically aware than the average white prisoner mainly because of the whole process of racism that he’s confronted with outside. He’s got a general awareness of not just racism but society as a whole that is at a higher level than the average white prisoner. On that basis there’s generally a tighter sense of unity among black and minority prisoners.

What was it like being a political prisoner when you first went in to prison in 1975?

There was a whole heap I learned when I was in prison especially from people who were more conscious than me, mainly the Irish guys. This was the first time I had been to prison facing a big sentence and it was a shock. At the same time I wasn’t prepared to tolerate the racism right from the very beginning. Which is why I did thirteen years when I was only supposed to do twelve and I should have been out long before that.

I lost a week’s remission while I was on remand because me and the screws clashed. Either you cower to them or you resist. They don’t have to physically beat you – which they do anyway, they don’t have to verbally abuse you – which they do anyway. It’s their whole attitude; it’s hostility, ‘you’re a nigger, we’re the commanders and if we tell you to jump off the landing you jump’. The problem is if they tell me to jump off the landing I’m staying right where I am and that’s where the conflict comes.

In 1975 I met the Balcombe Street guys and some of the Guildford Four were in Brixton at the same time as me. I was already politically conscious and I started moving around with people of a similar mind. Sean O’Doherty was the first Irish prisoner I met. In prison I was meeting people who were giving me the Irish liberation point of view. The first thing I noticed which impressed me was their commitment to the Irish struggle. They’re not half-way guys. So even now, thirteen years later there’s people left inside who are as committed now, even more so, than they were thirteen years ago. You have to admire that in any people. Nelson Mandela is the same thing.

Irish prisoners in the early days got rough treatment from other prisoners.

The average English prisoner is conservative so they used to look upon Irish prisoners in the same way as the government does. In Parkhurst an English prisoner attacked an Irish prisoner. There was only one or two other Irish prisoners in the prison, so they were outnumbered. The Irish guy and the English prisoner were moved to the Scrubs. It’s generally known that these Irish guys do not mess about, they are serious guys. It would have come down to a full scale war if a guy, who I used to call Dr Henry Kissinger as a joke, some kind of peacemaker, hadn’t intervened and settled it between the English and the Irish. We black guys heard about it and we were prepared to go on the side of the Irish guys. Another incident was in Parkhurst where screws opened the doors of two English prisoners and they attacked an Irish prisoner. Any kind of English hostility against black and Irish prisoners the screws will support because it’s in their interest to keep prisoners divided as well as matching their own racism.

We had a lot of political discussions, were involved in protests and strikes. They proved the level of their political commitment. It was a learning process; I’m sure I learned more from them than they learned from me. They used to ask me questions about aspects of the black struggle and we used to have good political discussions.

They gave me a lot of support. For example when I was in Gartree, through the racist practices of the governor there (he was known as Exocet until he had a bucket of shit thrown over him and then he was known as shithead), I refused to work. I didn’t work anyway but this was official. They were fining me and I was refusing to sew mailbags. So I didn’t get any pay for two months. Every week for two months four Irish prisoners – Liam Baker, Johnny Ace, Sean Kinsella and Tip Guilfoyie used to buy stuff for me. I used to flash it in front of the screws and say ‘I’m all right, I’ve got this’. It’s that kind of action that showed their commitment to back up prisoners who are fighting against the system.

The impact of Irish prisoners has been positive. It’s through their fighting for their rights that other prisoners can sit back and say, even if they don’t like the Irish prisoners, they have to admire them for their resistance. In a lot of their struggle they’ve been isolated and alone. Two or three Irish prisoners will be fighting for something that’s of benefit to all prisoners but they would be the only ones because all the other prisoners say ‘well they’re Irish they’ve got no chance of parole’. The English prisoners have still got this hope of getting out whereas the Irish prisoners are not restricted by what I call the parole syndrome. It’s been a long struggle for them but they’ve gradually earned the respect not only of the prisoners but even of the screws.

Did other prisoners see the advantage of solidarity from these examples?

Yes and no. Take the average English prisoner who would look upon himself as a criminal, they can keep up a resistance while they’re out on the street but once they’re arrested ‘it’s a fair cop guv’. So if they get a sentence of 25 years they’ll sit down and do it. This is one thing that baffled me. And the longer the sentence the more it baffled me. I cannot understand why a prisoner accepts the sentences they do. Whereas Irish prisoners saw it as their political duty to escape. Now English prisoners say `I’ve got a twelve year sentence maybe get parole’. So you get that basic difference in attitude and therefore a different performance and activity in the prison. And this has led to certain conflicts between English and Irish prisoners. Over here in England, prisoners accept their sentences. That is the major difference between prisoners in this country and all over the world. I used to read about escapes of prisoners in Peru, Brazil, South Africa – all over the world. That couldn’t happen here.

This attitude also affects whether you’re going to have a strike for a pay rise for example. As you know prisoners are paid an insult for wages. I never worked but the wage I was supposed to be on was less than £5 per week. The conservative attitude is an eternal damper on any resistance or any movement towards change by prisoners.

When I got my sentence I was put on D wing in Scrubs. The majority of people there were doing life sentences. I was under the impression that everybody would be wanting out. But then I met up with the damper. There may be a man determined to escape but for that one there will be ten who don’t want to and some of them will be prepared to go to the authorities and grass in the hope that they might get parole. Parole is one of the most serious questions. Before 1983, before Britton’s announcement on parole, the average parole was about 15 or twenty months. Some got four or five years. Before ’83 parole was the best form of control. Then there was the outcry about increase in violent crime. So they said no parole for those doing five years or for violence or drug trafficking. I remember I was in Wakefield when I heard this on the news. I was shocked. I knew I wasn’t going anywhere for the next four or five years. I thought the whole prison system would go up. The average prisoner expected to get some parole. Then suddenly they are making prisoners who are already captured responsible for what people were doing on the streets at that time. It’s a double punishment.

But I went downstairs and people were still playing snooker and watching their Coronation Street as though nothing had happened. I was amazed. Nine of us got together and made some petitions and said we were going to strike the following week in opposition to Brittan’s announcement. Out of 160-170 prisoners on my wing only another three people signed it apart from us nine. We tried to organise a national strike and there were strikes in other prisons.

People look at it from an individual not a collective point of view. Brittan said there would be parole for those categories in exceptional circumstances. Everyone thinks of themselves as an exceptional circumstance. It’s only now that the effects of that announcement are being felt. People are realising that the policy is continuing. Every now and again to justify holding people longer the government talks about rising crime.

What effect did FRFI have in terms of organising in the prisons?

I came across FRFI in 1981 when I was in Hull. An Irish friend of mine had the paper and I read it so I wrote off. FRFI is important for prisoners as a whole. There’s a lot of prisoners isolated. They want some kind of political feedback, some hope. FRFI gives them some hope by showing it is possible to fight against repression that they’re facing every day. When I read it the first page I turned to was Prisoners Fightback to read about who was where and who had done what to who.

At first only Irish prisoners had it but its circulation has grown. It sets forward ideas of organisation about prisons which prisoners need. When I came to prison it was after PROP (National Prisoners Movement) and there was nothing. FRFI has continued and is in contact with more prisoners. I see it as a foundation of organisation. It gives people ideas and shows there are alternatives so long as you’re prepared to fight and organise for your rights. So it’s had an important effect on prisoners.

There haven’t been any big protests in English prisons since the Scrubs and Albany in 1983.

This is one reason why I wrote to FRFI about the prison movement last year. If there’s no solid struggle then it’s hard for you on the outside to know what’s going on. They’re still murdering prisoners but it’s on a low level. When a serious riot or disturbance takes place you can respond. But between big events a lot of political work needs to be done. So prisoners do need to keep writing and letting you know what’s going on.

The Albany and the Scrubs protests resulted in a limited victory and won some legal representation for prisoners.

Even now the state is biting into that. You can get legal representation on their say-so. It should be automatic. I was charged with assault last year. In fact they assaulted me. But when I asked for legal representation it was refused. So I didn’t participate in the proceedings, was found guilty and lost more remission. They know that if they give prisoners legal representation, 85% of their charges are going to be kicked out.

At one point you linked your demands for prison rights to the position of prisoners in the Six Counties who got half remission. Now that right to half remission is being removed.

If parole is going from a half to a third in the Six Counties there is going to be a lot of disappointment for people. The state is cracking down. It’s just a continuation of the brutal policies of the British in trying to break down resistance in Ireland.

When half remission was introduced in 1976 in Northern Ireland prisoners felt that the same should happen here. So prisoners started organising for half remission here. Half remission was introduced in Ireland as a result of the hunger strikes which the British claim to have defeated but that is open to debate. Prisoners in the Six Counties were given their own clothing, food parcels. So we organised around these issues. This led to national strikes in the dispersal prisons in ’80, ’81, ’82 and ’83.

We were organising strikes each October in an attempt to better our conditions. The strikes themselves were successful and were supported by the majority of prisoners but we didn’t gain anything. We didn’t just need one strike a year we needed constant resistance in any form necessary. The Irish prisoners won concessions after four years on the blanket. When I think of those hundreds of prisoners making that kind of protest, not including the hunger strike itself! We used to argue that British prisoners wouldn’t need to have to do half of that to get these things introduced here because they were already in operation there. So we would be riding on the coat tails of the Irish struggle so to speak. We could have got some changes but we couldn’t get the support needed.

If you want something, major changes, you have to fight for it. If prisoners in Britain really want half remission, food parcels or four visits a month they have to fight for it. The state will not give prisoners these things on a plate. What you’ve got in prison at the moment is a lot of angry individuals who want changes in their individual conditions. They’re suffering in the blocks, they’re moved out on lie downs. Those individuals cannot change the system. They’re made to suffer all the more, they’re used as examples. The need for collective action in prison is paramount. Otherwise individuals will continue to suffer. Whatever the action the prisoners choose – strikes, refusing to bang up, riots – whatever is necessary to bring about change. Obviously the state is going to resist, that is expected. Prisoners don’t have any choice. Either you fight or you suffer.

Prisoners in Ireland have an active movement of support from relatives and from a political movement. Do you see that as necessary here?

The Irish have built a tradition over many centuries of struggle and resistance. Irish people help their people inside. You don’t have that kind of tradition in Britain. Individuals in Britain have support from their relatives but not prisoners as a whole. So they have to start building up those links in the families and communities. To introduce a culture of resistance. Because of the experience of racism the average black prisoner is more conscious and aware. Black prisoners have built up a certain culture of resistance, not on the same scale as the Irish prisoners, but it is at a higher level than the average white prisoner.

The white prisoners they’ve got families and friends helping them but not a political basis. Whereas black prisoners are beginning to do that. This is part of the function of the organisation I have been working with since I came out, the African Caribbean Prisoners Support Group. We support black prisoners in their struggles against the system and we maintain links with them and their families and give them support. This culture of resistance is being built up. That is what is needed in the prisons as a whole.

A lot more prisoners are breaking out of the stranglehold of the parole system. A lot more are saying they’re going to fight for their rights. So I can be optimistic. But it still needs collective political action and decision making and it must come from the prisoners themselves. They have to make their own decisions. They obviously want as much support as they can get from outside.

The Labour Party and trade unions don’t campaign for prisoners rights at all.

The majority of people who go to prison are not millionaires. If those people in the city are involved in criminal actions they don’t go to prison they get knighthoods. The ones who go to prison are the men of the broke pocket tradition. The trade unions and Labour Party who claim they’re fighting for the working man should have some kind of policies as regards prisoners. The fact that they haven’t done this isn’t an oversight but a deliberate policy because of the association with criminality. But the question isn’t would they take a pro-prisoner stand but have they in the past? Prisoners have been there before the Labour Party. If they haven’t taken a stand for prisoners yet why should they do so in the future? When Labour are in power it’s only a continuation of the same conservative policies. I was inside under Tory and Labour governments and I saw no difference.

What sort of changes do you notice politically since you went into prison?

I was arrested in ’75 and there was a general feeling that the revolution was coming if not today then next week. Since Thatcher got into power there has been a resurrection of fascist ideology. The capitalist class has done well for itself but everybody else has been made to suffer. It’s a matter of an ebb in the tide of history. In some periods the progressive forces are making progress and moving forward and in other times it’s a period of reaction. We’re in the era of reaction now. Not just in Britain but across the west as a whole. The revolutionary parties have to re-group and rethink to combat the rising power of the forces of reaction.