The general election was a disaster for the Labour Party. Despite facing a Tory Party responsible for ten years of austerity which had savaged working class living conditions, a party led moreover by a proven racist, sexist, incompetent, coward and serial liar, Labour never landed a single body blow. Jeremy Corbyn’s disdainful declaration that he was ‘not a boxer’ was sheer arrogance: working class people had a right to expect some anger from him, some expression of raw class hatred for those who for a decade had imposed such suffering on millions of people – but it never happened. His ‘kinder, gentler politics’ was the height of self-indulgence. Prime Minister Johnson’s government now has a free parliamentary hand in implementing its reactionary populist programme. Labour’s collapse has comprehensively exposed the illusion that any real change can be achieved through the parliamentary system, by putting a cross on a piece of paper every five years. Any meaningful resistance to the reactionary programme of the re-booted Conservative Party, and the further attacks on the working class that are to come, will have to be built on the streets.

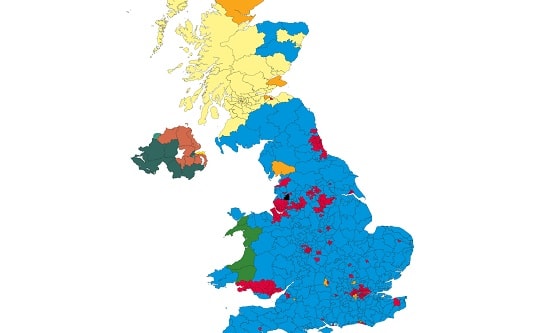

The results speak for themselves. Compared to its performance in the 2017 general election, Labour’s vote fell from 12.9 million to 10.3 million, with a net loss of 60 seats. Its total of 203 seats is the lowest since 1935, fewer than it gained in the post-Falkland War election in 1983. While the Tories increased their vote slightly by 330,000 to just short of 14 million, they were able to take a number of northern predominantly working class constituencies as Labour supporters either stayed away or switched their votes to the Tories or the Brexit Party. Younger people who defected from Labour tended to switch to the Lib Dems as a pro-Remain party. There were also a significant number of Labour abstentions in northern constituencies. This enabled the Tories to win 365 seats, a net increase of 48. The biggest winner was the Scottish National Party, which increased their vote by more than a quarter (980,000 to 1.24 million), raising their tally of MPs from 35 to 48.

Post-election analysis confirms a trend evident for some years: that those who voted Tory were predominantly elderly, without higher education qualifications, and likely to be outright homeowners:

- In 2017, the crossover age where equal percentages voted either Tory or Labour was 47. In 2019, this fell to 38.

- 42% of Tory voters were retired compared to 19% of Labour voters.

- 53% of Tory voters owned their homes outright compared to 28% of Labour voters; at the other end of the scale, 18% of Labour voters rented privately compared to 9% of Tory voters.

- 58% of Tory voters had education qualifications at GCSE level or below compared to 25% of Labour voters. On the other hand, 29% of Tory voters had a higher education qualification compared to 43% of Labour voters.

The principal reasons for Labour’s electoral collapse are clear: Corbyn’s widely-perceived inadequacies as a leader and the Party’s ambivalent position on Brexit. Nowhere was Corbyn’s weakness demonstrated more clearly than in his constant refusal to challenge the spurious claims of anti-Semitism. The only way to deal with these lies would have been to offer a ringing defence of the rights of the Palestinian people, but the concessions made over the last four years – the adoption of the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism, the expulsion of pro-Palestinian activists, the succession of apologies in the face of media and Zionist attacks, and a pro-Zionist position in the Manifesto – left Corbyn with nowhere to go. He and Labour effectively threw the Palestinian people under the bus.

The ambivalent Brexit position became part of the perception of a dithering leadership. Labour tried on the one hand to appeal to privileged workers, especially those in the public sector, who were pro-EU because they saw continued EU membership as sustaining a form of social democratic state which could underpin their jobs and living conditions. This layer sees a threat to those conditions arising from the sort of deregulation that would inevitably accompany a closer economic relationship with the US. Significant numbers of Labour supporters defected to the Greens and LibDems because they could not accept the commitment to continue to press for Brexit if Labour formed a government.

However, other better-off workers, those who had a stake in the system through home ownership and who depended on a pension rather than a high level of income, had different concerns: they saw the threat to their position to come from unwarranted largesse towards the poor in the form of excessive benefits which would undermine NHS investment, and their perception of uncontrolled immigration. They were the core of the Brexit vote in the northern constituencies, the so-called Red Wall. Labour could not afford to alienate this layer – but in the end it did, by pledging to hold a second referendum on a new Brexit deal. The Tories capitalised on this by pledging an extra £30bn NHS spending in what was a successful inducement to such voters to switch allegiance away from Labour.

Immediately following the election, John McDonnell resigned from the Shadow Cabinet while Corbyn announced that he would not lead Labour into the next general election, but would stay to oversee the selection of his replacement. Pressure forced this to be started earlier from 7 January 2020 and conclude at the end of March. There will be a renewed assault from the right-wing of the Labour Party led by potential candidates such as Lisa Nandy and Jess Phillips. From the so-called ‘centre-left’, Shadow Foreign Secretary Emily Thornberry has declared her candidacy and Shadow Brexit Secretary Keir Starmer is expected to follow. The likely candidates for the Corbyn wing of the party are either Shadow Business Secretary Rebecca Long-Bailey or Shadow Minister Clive Lewis. All are united in their determination to be seen to be rooting out supposed anti-Semitism within the Labour Party; Long-Bailey is particularly perfidious in reassuring the arch-Zionist Jewish Labour Movement that she agreed that Chris Williamson, the former MP for Derby North, should remain excluded from Labour. There will be nothing progressive in the leadership contest: it will be about personal ambition behind smokescreens of pious sentiments.

The idea that Labour can be anything other than an imperialist party is humbug. After 120 years of existence, all the Labour left has achieved is the election of a supposedly radical leader who would not fight when it really mattered. No one in the Labour left drew attention to the reactionary positions in the Manifesto on NATO, Trident renewal or Palestine. Now there are those who say there should be a renewed attempt to make the internal structures more accountable. Yet they do not address fundamental issues: Labour is first and foremost a parliamentary party and has to operate within the rules that bourgeois democracy sets down. Central to this is respect for ruling class law. Labour-run councils have used this as an excuse for their refusal to fight austerity, and instead to implement cuts in jobs and services. Far from challenging this, Corbyn supported by McDonnell instructed councils not to set illegal budgets three months after he was elected leader in 2015; the following year a change to Labour’s constitution made opposition or abstention on a legal cuts budget a potential disciplinary offence. However radical the motion passed on Palestine at the last Labour conference was, it will not affect Labour’s pro-Zionist position. Labour will not oppose Trident’s renewal, it will not call for withdrawal from the NATO imperialist alliance. Honest socialists in the Labour Party have now to recognise that it is a busted flush, and that in the words of Jonathan Cook, ‘Now is the time to put away childish things, and take the future back into our hands.’ Out on the streets and in working class communities is where we will build the movement we need – and that means outside of and in opposition to the Labour Party.

See also our earlier article written during the general election campaign:

Labour Manifesto: who will fight for it?

The communist, anti-imperialist position on the 2016 EU referendum can be read here:

EU referendum – The position of communists with a new introduction analysing the result