Tony Benn: airbrushed by the left

The death of Tony Benn on 14 March 2014 led to an outpouring of grief from both bourgeois politicians and socialist organisations across Britain. To the British left, Benn was the Labour Party MP-turned-socialist who, so the story goes, took a sharp left turn after serving as a member of government in the 1960s and 1970s. Little is said of his time in government, where he served as a cabinet member while Labour waged a dirty war in Ireland and defended Britain’s economic and political ties to apartheid South Africa; of his undercover dealings with the apartheid regime; or of his role in driving down wages and conditions in Britain. The myth of ‘Tony Benn – socialist’ was manufactured by the opportunist left at a time when sections of the black and Irish working class were breaking with the Labour Party. The truth is that Benn never did a socialist thing or led a serious movement in his life, but he talked and wrote about it.

Benn’s parliamentary career

Tony Benn became a Labour MP in 1950, a time of British military suppression of the Mau Mau in Kenya and the liberation movement in Guyana. The Labour ‘opposition’ defended British brutality as it had done in office. The 1964-70 Labour government brought Benn into the cabinet. In July 1966, as Minister of Technology, his department made hundreds of secret shipments of nuclear material to the Zionist regime in Israel. He later claimed ignorance of the deal, which went ‘totally against the policy of the government’. Labour’s real ‘policy’ was shown within a year of Benn’s appointment, offering full political support to Israel’s assault on Egypt during the May 1967 war and drawing up plans to send the British Navy to fight the Nasser government.

In 1969 Benn supported the Labour government sending troops to the North of Ireland. The 1974-79 Labour governments instituted a campaign of criminalisation, torture and detention without trial, aiming to terrorise the nationalist community into giving up their struggle in the Six Counties. Neither Benn nor any other ‘left’ Labour MP opposed the introduction of the 1974 Prevention of Terrorism Act, aimed at intimidating supporters of the Irish struggle in Britain. As David Reed wrote, ‘Benn sat in numerous Labour Cabinets and raised no objections to the Labour Party’s record of brutality and terror in the Six Counties of Ireland’ (Ireland, the key to the British revolution, p327).

The Labour Party played a key role in defending the apartheid regime in South Africa. In 1968 Benn signed a contract with Rio Tinto Zinc to extract 7,500 tons of uranium from the Rossing mine in Namibia, illegally occupied by South Africa despite a UN ban. By the mid-1970s, South Africa remained Britain’s second largest export market. In 1976, the year of the Soweto uprisings, while Benn was Energy Secretary, Britain accounted for 50% of all foreign investment in South Africa. In January 1977, Labour approved an IMF loan to the apartheid state. The Labour government had used Britain’s UN veto four times – all in defence of apartheid. Elsewhere it provided political cover as British Aerospace provided fighter jets to the Suharto dictatorship in Indonesia, assisting in the brutal suppression of the East Timorese liberation movement. The Labour government defended the Shah of Iran as a mass popular revolt against the autocrat built up in 1978.

Labour’s war on the Irish, support for apartheid and defence of brutal, anti-communist regimes was mirrored in its domestic racism and through attacks on the working class in Britain. Benn remained in government as Labour implemented IMF-dictated cuts in state spending in 1976. The black working class was targeted by the racist 1971 Immigration Act, enforced fully by the Labour governments of the 1970s; it was tightened in 1977 to include ‘probation’ periods for migrant marriages. Asylum seekers were detained and by the mid-1970s over 200 black people a day awaited deportation. Benn’s role had been to mouth opposition to racism, while doing nothing that would threaten his position as a leading figure in the most reactionary Labour government so far. In November 1979, speaking on a platform at a demonstration called by the Campaign Against Racist Laws, Benn was heckled by black and Asian activists for his government’s role in implementing racist laws.

‘Elder statesman’ of the British left

Labour’s defeat by Thatcher’s Conservatives in 1979 signified crisis. The end of the post-war boom had led to recession in the 1970s, a time of ‘winters of discontent’ and mass strike action; middle class voters had not been convinced of Labour’s abilities to steady the ship. At the Labour conference in 1980, a year before he stood for the Party’s deputy leadership, Benn’s speech contained a wishlist of radical sounding suggestions for the next Labour government: to abolish the House of Lords, return economic decisions from Europe to Westminster, give more workplace power to the unions etc.

A process had begun to establish Benn as the ‘socialist’ elder statesman. The opportunist left organisations of the time, led by the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and the Militant, engaged in a deliberate cover-up of Benn’s political record. Benn was elevated as a leading ‘anti-fascist’ – despite his inaction while Labour deported and locked up black people. Benn was now an ‘anti-apartheid’ campaigner – despite Labour’s consistent support for the racist regime. He was even welcomed as a supporter of the Troops Out Movement – despite Labour’s appalling record in Ireland in the 1970s, over which Benn admitted he had remained silent.

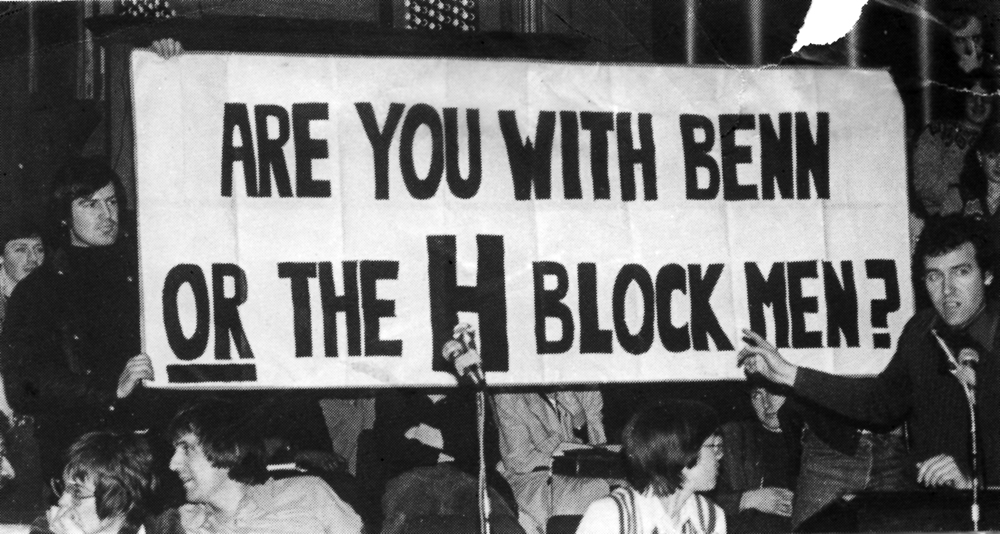

The British left’s airbrushing of Tony Benn’s image, as a principled socialist fighter inside an apparently reformable Labour Party, made sure social democratic politics remained dominant and revolutionaries were marginalised. In summer 1981, with uprisings taking place across Britain, Benn attacked the working class youth involved and said ‘the Labour Party does not believe in rioting as a route to social progress nor are we prepared to see the police injured during the course of their duties’. The same year, not one Labour MP expressed any public support for the Irish hungerstrikers, rejecting demands that they be recognised as political prisoners. During the 1984/85 miners’ strike, Benn withdrew a motion to the Labour Party calling for action. From Belfast to Brixton, the Labour left mounted no serious opposition to Thatcher’s programme. The hungerstrikers were murdered by the British state, the miners were defeated as Kinnock and Benn’s Labour Party attacked their ‘violent’ tactics, and working class youth, with all their revolutionary potential, found no political support.

Meanwhile, Benn excused British involvement in the Malvinas (Falklands) war, telling parliament, ‘There is unanimity in the House of opposing the aggression of the (Argentinian) Junta. There is also unanimity on the right of self-defence against aggression.’ His ‘anti-war’ stance meant he supported sanctions against Argentina, a position he also took in 1990 when he called for a longer period of sanctions against Iraq. The sanctions that followed the first Gulf War were fully supported by Labour in opposition and in government. They claimed the lives of an estimated 500,000 children.

In the late 1970s, as Benn’s Labour government ruthlessly defended the interests of British monopoly capitalism, from Ireland to South Africa, Benn claimed that British imperialism had ceased to exist:

‘Britain has moved from Empire to Colony status. It is a colony in which the IMF decides our monetary policy, the international and multi-national companies decided our industrial policy and the EEC decided our legislative and taxation policies.’

He is talking about the second most powerful imperialist nation in the world! In 2001, the year Tony Blair’s Labour government sent British troops to invade Afghanistan – its third military intervention in four years – Tony Benn went one step further in his reactionary argument, claiming that ‘Britain is now, in effect, an American colony, seen in Washington as an unsinkable aircraft carrier’, finally deciding that Britain is ‘a colony between Washington and Brussels’ (BBC interview, 2001). Benn’s position was just a cover-up for the City of London as the world’s largest financial centre, and let British imperialism off the hook. The subsequent Blair/Brown governments showed that the Labour Party was ready and willing to wage war to defend the parasitic interests of the City of London.

Despite all the ‘anti-war’ talk, Benn remained loyal to the imperialist party that he had represented. When he retired from parliament, Benn was appointed chair of the Stop the War Coalition, speaking at demonstrations against the invasion of Iraq. Yet, despite the horrors the Blair Labour government brought to Iraq and Afghanistan, Benn agreed to assist Blair’s 2005 general election campaign, spending three hours phoning Labour voters from a list provided by party headquarters. His opposition to Blairism apparently evaporated: ‘To have them ring me to help them out shows this election means Labour is returning to what it was … it is a trade union party and a socialist party. It has done good things. I am voting Labour’. He went on to make it clear that, ‘My own opinion is that the Labour government is the right thing.’

Following Tony Benn’s death, his stylists on the British left have written glowing tributes to a mythical life of activism. Charlie Kimber writes that Benn ‘changed through discovering something about socialist thought and, crucially, through the experience of workers’ struggle in the early 1970s’ (Socialist Worker, 11 March 2014). Benn is described as shifting to the left during his years in the Callaghan government of 1974-79, ‘complaining’ and ‘arguing’ as a cabinet member. The Socialist Party (in those days known as the Militant) thinks that Benn’s sudden ‘shift to the left’ started even earlier, from 1971, when he ‘championed’ workers’ struggles. For the Communist Party of Britain Benn’s ‘journey’ was even more simple: ‘Starting off on the right of the Labour Party, he moved steadily to the left and developed a deep understanding of the need to combine parliamentary politics with struggle in the streets and workplaces’ (Morning Star, 14 March 2014). Neither Ireland nor imperialism are mentioned once in these three obituaries.

Tony Benn made a career out of defending the Labour Party. As a member of a reactionary government, he took no action to oppose its racism and imperialism – in the case of Ireland, he couldn’t muster a word of opposition. The British left has attempted to re-write history and present Benn as a principled, socialist fighter, a figure of progress in an increasingly right-wing Labour Party. But within his many-volume memoirs, Benn never expressed any regret for his positions in the service of a party that for his entire political career stood for British imperialism. At the Campaign Against Racist Laws demonstration in 1979 a young black activist responded to Tony Benn’s speech with the warning, ‘beware false friends.’ We would do well to listen to his advice.

Louis Brehony