Image: The Tories’ General Election poster 1979, the year in which Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister

As Britain takes the first step towards exiting the European Union (EU), the Labour Party is facing meltdown. It is trying to maintain the leftist facade of the four years of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership while responding to an electoral disaster for which Corbyn’s incompetence as a leader is largely responsible (See ‘General election – Labour faces meltdown’ on our website). However, what socialists also need to explain is why, after ten years of vicious Tory austerity, 47% of those in social classes DE (semi-skilled or basic manual jobs) who voted went for the Tories but only 34% for Labour (YouGov), or, which is another way of looking at the result, 58% of those with GCSE qualifications or lower voted Tory but only 31% supported Labour. In other words, a large section of the working class voted Tory, despite widespread and continuous impoverishment. On the face of it, this is an extraordinary situation. How has it come about?

The changing character of the working class electorate

For the answer we have to look back to 1979 when a large section of junior administrative and skilled manual workers – the so-called C1 and C2 social classes – defected from Labour to Thatcher’s Tories in the general election. These workers became tied to Thatcherism as they benefited from both Right to Buy and the Tory privatisation programme of the 1980s. Now retired or approaching retirement, they are a relatively privileged layer of the working class which remains a bastion of nationalist and individualist reaction, and which is once again playing a decisive role in electoral politics – three years ago over Brexit and now in the 2019 general election. 30-40 years ago they had not needed a higher education or even A-Levels to get a job with sufficient security to buy a home or make a quick buck from the sell-off of shares in the former nationalised industries such as oil, gas, water and electricity. They happily subscribed to the individualist ethos that Thatcher cultivated and then to the chauvinism following the 1982 Malvinas War that led to the landslide Tory election victory in 1983.

Even for those who could not take advantage of Right to Buy, rising real wages for large sections of the working class made buying a house a realistic option especially outside London in the 1980s and 1990s. With the rise in land and therefore house prices particularly following the 2007/08 financial crisis, the proportion of homeowners started to fall and is now about 64% of all households. However, this masks a change in the proportion of outright homeowners as opposed those who are mortgage holders:

- In 2009/10, the number of outright homeowners was 6.83 million while 7.70 million homeowners were buying with a mortgage.

- In 2017/18, the proportions had reversed: 7.89 million were outright owners, while the number with a mortgage had fallen to 6.89 million.

- In 2009/10, the number of outright homeowners aged 65 and over was 3.93 million; eight years later it was 5.03 million.

- Outright homeowners make up 75% of all households where the Household Reference Person is aged 65 or over; the remaining 25% is made up of 430,000 private renters, just over one million social renters, and 300,000 mortgage holders.

- There are a further 1.69 million people aged 55-64 who also own their homes outright and 1.15 million in the same age range who are coming to the end of their mortgage period.

These are people with a significant stake in the system, but although they are asset-rich, a significant proportion are from a working class background and therefore often income-poor. 21.1% of outright homeowners are in the poorest household income quintile; many are living in relative poverty. A further 24.5% are in the next poorest quintile.

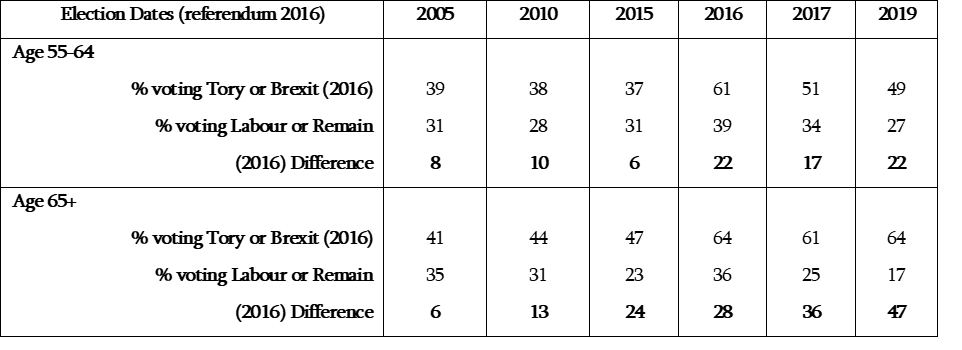

This layer loaned its vote to Labour in 1997 in the wake of the Tory corruption scandals in the 1990s and splits over EU membership. However, in subsequent general elections it drifted back to its natural Tory home, and by 2010, the scale of the defection was sufficient to cost Labour its parliamentary majority. The margin by which those in the age ranges 55-64 years old and the over-65-year olds voted Tory as opposed to Labour widened as the layer approached retirement (see Table 1).

Table 1 (Source: Ipsos-Mori)

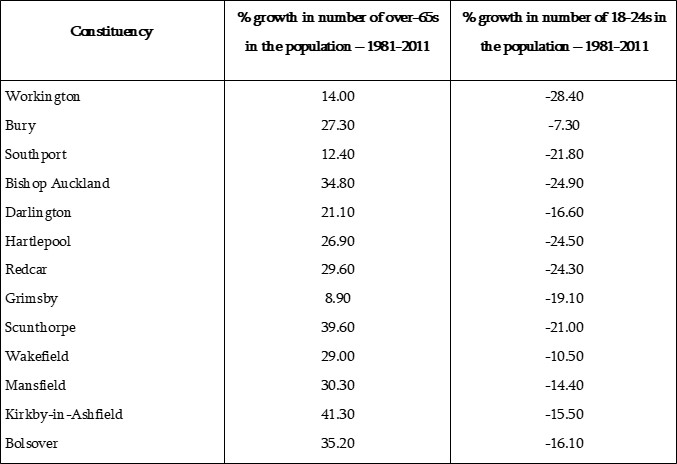

These workers have never changed their reactionary outlook. During the 2010 general election they rejected what they regarded as Labour’s policy of uncontrolled immigration and limitless spending on state welfare benefits even though the realities were quite the opposite. By 2015, a chorus of Labour politicians was arguing that the Party was abandoning its heartlands for which the so-called Red Wall of northern England became a symbol in 2019. Labour performed disastrously in these seats because population shifts gave even greater electoral weight to this stratum. Research undertaken by Centre for Towns shows that in a sample of 13 of the most northerly seats of the Red Wall that Labour lost in 2019 there were dramatic increases in the proportion of their population aged over 65 between 1981 and 2011, and a hardly less dramatic fall in the proportion of young people aged 18-24 (see Table 2).

Table 2 (From Centre for Towns, assembled by John Elledge, ‘How demographics explains why northern seats are turning Tory’, New Statesman 17 December 2019)

Younger people have for years now been migrating from towns into cities, a process driven first by the growth of university education over the period, and second by the greater professional employment opportunities associated with this. For older people with an outstanding mortgage or an outright homeowner, migration is much less of an option: the home is an asset on the one hand, but a millstone on the other with the responsibility and cost of maintenance, and always under threat from the future costs of social care.

Workington in West Cumbria was identified by the Tories as a key target seat (photo: Dave Wilson)

Nonetheless this layer has something, and it defends what it has through its political allegiance to the Tories. Luke Pagarani in The Guardian (21 December 2019) argued that for these voters ‘retired or coming to the end of their careers … A small hoard has been salvaged from the UK’s long post-imperial decline, and only those whose fealty is proven can claim their share’, adding that they were worried that Corbyn would be ‘profligate and squander the security inherited from a time when Britain was more powerful…[they] wanted the patronage of the powerful, not to challenge their power.’

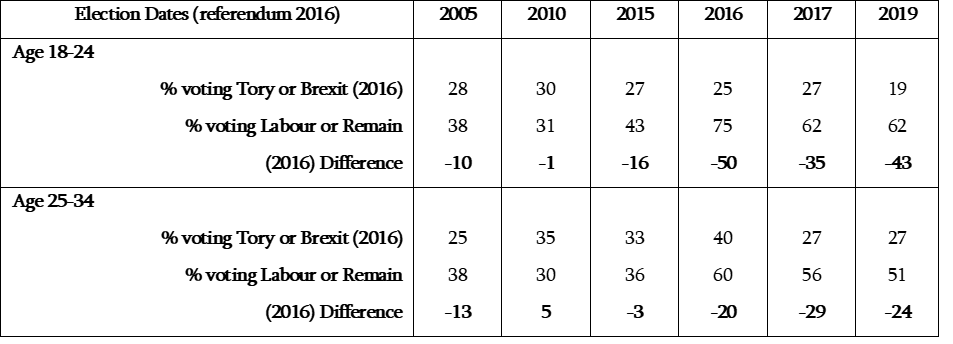

When Labour politicians speak about reconnecting to their heartlands, the question is how reactionary they will have to be in order to secure the support of this ageing Thatcherite layer whose votes are crucial if Labour is to win a general election in the future. At the moment, younger people are voting Labour in similar proportions as older people are voting Tory (see Table 3).

Table 3 (Source: Ipsos-Mori)

However, if the 2019 voting turn-out by age group was similar to that recorded by the British Election Study for 2017, 38% of the voting electorate would have been 55 or older, far more than the 27% of voters aged between 18 and 34. Ipsos-Mori figures show those in social classes D and E aged 18-34 voted 63% Labour and 18% Tory; this was reversed for those aged 55 or over: they split 53% for Tory and 25% for Labour. However, there were far more potential older voters, and a higher proportion turned out (64% vs 37%). In other words, Labour as a parliamentary party will completely focus on winning back the votes of the elderly and, in the absence of any serious working class movement, this means pandering to their backwardness even more. It is not possible to create an electoral coalition of these different layers. White collar higher education graduates in the cities may have a higher income and a degree of job security if they work in the state sector. But few are able to afford to purchase a home especially in London and this limits their stake in the system, and many are working in insecure conditions for agencies or other forms of precarious employment.

This however will not deter supporters of the Labour Party from intensifying their efforts to tie young people to the Labour Party. The job of communists is to prevent this from happening by building an anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist movement outside of and against the Labour Party. The only sign of any movement since Corbyn’s election as Labour leader in 2015 has been the movement of young people on the streets against climate change. Corbyn’s vaunted anti-austerity movement never happened as it would have had to challenge Labour-run councils implementing service and job cuts, and demand that they break the law. Such a step would have split the Labour Party immediately, and it was quickly shelved by Corbyn and Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell in a letter sent to Labour councillors in December 2015 which instructed them to set legal, pro-cuts budgets. This is not going to change over the next five years, whoever wins the leadership election. Labour-run councils will continue to cut budgets and jobs with the protection of the trade union leadership which, faced with more drastic anti-trade union legislation, will be even more opposed to serious action in defence of the working class.

The new movement we need can have no truck with the racist, reactionary layer which is determining the direction of electoral politics. Labour’s election manifesto already contained the key elements of a chauvinist, pro-imperialist standpoint – its commitment to the imperialist NATO alliance, the target of 2% GDP spend on defence, its defence of the colonial-settler Zionist state and the oppression of the Palestinian people. These policies have been ignored by the opportunist left in its determination to declare the socialist character of the manifesto. In 1979, the Revolutionary Communist Group joined Irish and black workers in refusing to vote for Labour in the general election because of its appalling governmental record during the preceding five years: the state-sponsored racism against black and Asian people; the criminalisation and repression of the Irish freedom struggle; and its determined opposition to the liberation struggle in apartheid South Africa. Forty years later, Labour remains a party fit for imperialism.

Robert Clough

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! No 274, February/March 2020