‘The Victorians paid the price for housing people in fundamentally unsatisfactory, unhealthy places when cholera and typhoid came calling. We’re now in an era of new novel diseases, which will just love the modern equivalent of Victorian slums, where people do not have enough space or, quite possibly, enough ventilation or sunlight.’ (Gabriel Scally, professor of epidemiology at the Royal Society of Medicine)

It is clear that the worst impact of the coronavirus outbreak in Britain has been borne by the poorest sections of the working class. The highest rate of fatalities from Covid-19 has been in the most deprived parts of the country’s major cities where the poor are crammed into overcrowded, poorly ventilated and unsanitary housing. Those living in cramped, unsuitable housing are more likely to suffer a wide range of illnesses such as cancer, respiratory and cardiovascular diseases and diabetes – all of which increase the risks associated with coronavirus, especially for people from a black or minority ethnic background.

Now, with unemployment soaring, the crisis in the private rented sector is set to explode, with the lowest-paid and young workers in particular falling into arrears and increasing numbers facing the risk of imminent eviction. Britain was already experiencing an intense housing crisis, with homelessness and housing insecurity at record levels, a desperate lack of council housing and unaffordable rents. CAT WIENER reports.

Covid-19 – ‘a housing disease’

It is not surprising that the greatest incidence of Covid-19 has been in the most overcrowded areas, with 70% more cases than the least crowded areas. The highest mortality rate in the country is in the Labour-run east London borough of Newham which, infamously, also has the highest level of overcrowding, the highest number of households in temporary accommodation and the highest level of homelessness in Britain. Brent, in north London, which has the second-highest fatality rate, has the most homes in multiple occupancy. While overcrowding for white households in England is around 2%, the figure rises to 30% for Bangladeshi households and 16% and 15% for Pakistani and black African households respectively. Overcrowding is the result of unaffordable rents – which can be as high as 60% of income for the poorest, and generally around 40% of income in London – and lack of council housing.

The worst housing of all is reserved for those in temporary accommodation. The most recent quarterly government figures show that there are currently 62,280 families living in temporary accommodation – the highest number recorded since 2007 – including more than 35,000 children. 5,400 (9%) of these households are living in emergency B&Bs and hostels, sharing kitchens and bathrooms with four or five other families and usually forced to live and sleep in a single room. Under these conditions, lockdown becomes an effective prison sentence. Temporary housing is the new slum accommodation: overcrowded, cramped, lacking adequate ventilation or outdoor space, infested with vermin, wracked with damp and mould, with broken and dangerous furniture and fixtures. What ‘social distancing’ or self-isolation is possible for families in such conditions? One pizza delivery driver, Walid Alhusien, told The Guardian he lives with his wife and five children in a room just four metres square in Mitcham, south London. ‘They have to share a bathroom and kitchen with four strangers. He fears what might happen if the virus strikes. “I can hear two of my neighbours coughing all the time,” he said. “It is really scary. I want to protect my family but what can I do?”’ (The Guardian, 12 April 2020)

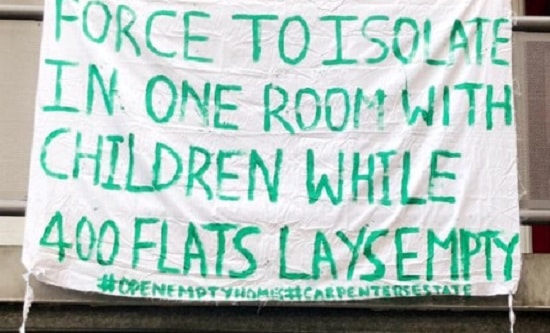

One woman in Newham made the point sharply. In April, Marsha was forced to self-isolate with her daughter in a single, tiny room in council-run temporary accommodation. She made a banner demanding to know why she and so many others were forced into such conditions, while 400 council flats in the nearby Carpenters Estate remain empty and boarded up. She told the Focus E15 housing campaign she had made the banner to say ‘she had had enough’ because : ‘People from deprived and over-populated areas such as Newham are more likely to catch the virus…. I am angry and frustrated that I and many other families living in temporary accommodation have been disregarded by the Council. With so many empty homes around Newham such as those on the Carpenters Estate, it is totally inhumane and unacceptable to have families living in one room with children…The least they can do is open them up.’ That is the demand we should be putting on all councils – especially Newham, whose head of housing, John Gray, while conceding that Covid-19 was ‘a housing disease’, added disingenuously that the council was ‘trying to put together thoughts and plans on how to address that’. Meanwhile Newham has a waiting list of 36 households for every council house vacancy in the borough.

For asylum seekers who are frequently housed, illegally, with two or three strangers sharing a single room and even a bed, the situation is even worse.

More than 150 years ago, Engels chronicled the living conditions of the new industrial working class in London and Manchester.* They were crowded into slums – dangerous, life-threatening, insecure housing that cut short the lives of workers already weakened by hunger and deprivation with waves of epidemics of typhoid, tuberculosis and cholera. These remain the conditions in which millions live today in vast favelas and shanty-towns across the globe, wherever capitalist exploitation dominates social relations. Increasingly these are the conditions that dominate housing in Britain for the poorest sections of the working class. Last year research by the Nationwide Foundation pointed out that, fuelled by changes to benefit, a ‘slum tenure’ was being created at the bottom end of the market. Capitalism has no interest in the housing of the mass of the working class beyond the revenues it can generate for the property owning classes.

‘An avalanche of evictions’

The systematic destruction of council housing over the past 40 years has forced more and more people into the private rented sector. Today the sector represents 20% of all households, and private rent brings in even more money than mortgage interest repayments. No surprise then, that housing minister Robert Jenrick was quick in March to announce a mortgage holiday for property-owners, including buy-to-let landlords, but with no commensurate protection for renters. There was some guff about the mortgage holiday allowing landlords to be ‘flexible’ about rent from workers who had been laid off at the start of the crisis – but the reality is that, according to ONS figures, rents actually rose 1.5% in the 12 months to April 2020 – from 1.4% in March 2020.

The impact of this crisis on private sector renters is going to be disastrous. According to the Resolution Foundation, 30% of Britain’s lowest-paid workers have lost their job or been furloughed in the past two months (compared with only 10% of those in the top fifth of earners.) Workers aged under 25 – many of whom work in the catering and hospitality sectors – have been particularly badly affected, with one in three young people having been furloughed or lost their jobs completely, and over one in three having had their pay reduced since the crisis started.

These are the sections of the working class most concentrated in private rented accommodation – 38% of private renters are already amongst the poorest third of British society. At the same time they are those with the least to fall back on – two-thirds have no savings at all.

By 4 May, more than two million people had applied for Universal Credit, a rise of 69% over just one month. But Universal Credit does not fully cover most rents in the private sector, even after a temporary restoration of the housing benefit component to its 2015. Already by June 2019, 75% of those in receipt of Universal Credit were in rent arrears. It’s expected that, In the wake of the impact of the coronavirus crisis, a further 2.6 million people will fall behind on their rent.

Under mounting pressure, the government eventually conceded that no eviction proceedings would be carried out by the courts until 25 June, and that the eviction notice period given by landlords would be extended from two to three months. Meanwhile, eviction notices are still dropping on doormats and while all possession hearings are temporarily stayed, as the housing barrister David Renton put it, this is the legal equivalent of putting food in a freezer. The cases are still there, ready to be thawed out at any moment. This includes thousands of pre-coronavirus cases, and thousands more to come as rent arrears inevitably build up over this period. No wonder the body representing London councils has warned of ‘an avalanche of evictions coming down the line’ if the suspension is not extended beyond its current 25 June expiry date.

The response of the opposition Labour Party has been equally useless. Its ‘five-point plan’ would simply extend the eviction suspension by six months, give renters two years to pay off any rent arrears built up during the crisis, and includes a request to the government to consider a temporary increase to housing benefit. It simply extends the debt of those least able to afford it, while ensuring landlords’ income streams are protected.

The reality is that tens of thousands more people will be made homeless, forced onto the streets or into squalid temporary accommodation, at a time of already record levels of homelessness.

Fight for working class housing

The government has made it clear that its only concern is to find ways of regenerating profits and clawing back the billions it has spent on shoring up the economy. Short-term measures it was forced to implement to protect sections of the working class as it chaotically attempted to prevent the immediate spread of coronavirus are being shelved. The successful ‘Everyone in’ programme that saw around 5,400 rough sleepers offered accommodation in hotels, at a minimal cost of £3.2m and which is credited with preventing a potentially devastating epidemic amongst the street homeless, is being dropped. The homelessness minister Luke Hall has threatened that homeless migrants with no recourse to public funds who were temporarily housed under the scheme will now face pressure to accept ‘voluntary repatriation’.

Meanwhile, it was perhaps inevitable that among the first people to be encouraged to go back to work were the construction industry and estate agents. The housing market is a key player in generating profits for capitalism. Privately owned land, and by extension, housing have become vital assets at a time when productive avenues for capital investment have dried up. The ruling class is terrified that the coronacrisis could lead to a slump in land values and property prices. And so, in order to boost housing sales and the profits of the construction companies and developers, councils have been asked to waive both their statutory Section 106 requirements for any kind of ‘affordable’ housing in private development schemes over the coming period, as well as the community infrastructure levy through which developers invest in the local area they are about to extract profits from. Even given the limited redefinition of what constitutes ‘affordable’, Section 106 delivered 49% of all new sub-market-price housing in England in 2018/19.

The major housing associations and some on the Labour left have called on the government to seize the opportunity to deliver thousands of units of ‘social housing’ over the coming period. It is clear, as it has been for decades, that only a massive building of council housing can begin to tackle the housing crisis. But it is equally clear that it cannot be achieved without concerted action by the working class. Council homes at a social rent do not generate sufficient profits for private capital. If we want decent housing we are going to have to fight for it.

No evictions!

Safe, secure and affordable housing for all!

Fight for social housing!

* The condition of the working class in England, Frederick Engels, 1845