Capitalism is in deep and unending crisis. Profit increasingly takes a parasitic and criminal form: interest, speculation, tax havens, money laundering, organised crime, financial fraud, rigged markets. These are the means by which capitalists retain their profits as they are compelled to battle with each other for a share of the surplus value. Cheating and corruption become necessary to monopoly capitalism in crisis and is invaluable to the ruling class. Trevor Rayne reports.

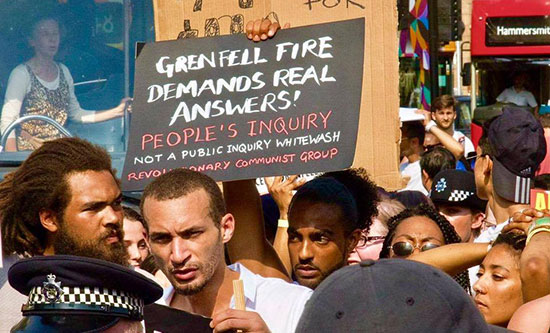

The fire at Grenfell Tower exposes the scale of corruption that permeates authority in Britain. It is driven by corporations scrambling for profits, bending rules and regulations and breaking them to do so. In these calculations, human beings must yield profits and they are disposable. This crime was years in the making and the guilty hands are many, but the names will be few. The culprits hide behind masks of respectability and are protected by the narrow terms of reference of the public inquiry.

Construction accounts for about 6% of the British economy. It is profitable and construction companies have benefitted from successive government policies and devised them; big corporations are ‘right inside the room of political decision making. They set standards, establish private regulatory systems, act as consultants to government, even have staff seconded to ministers’ offices’ (Colin Crouch, The Strange Non-Death of Neo-Liberalism). From central government to local government, British democracy is corrupted. As Lenin wrote a century ago: ‘A monopoly, once it is formed and controls thousands of millions, inevitably penetrates into every sphere of public life, regardless of the form of government and all other “details”’ (Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism).

The attack on public spending, resulting from the capitalist crisis, has benefited construction firms. Council spending cuts have reduced resources available for enforcing regulations. Furthermore: ‘Building regulations for fire prevention and safety have not been reviewed for more than a decade, even though most regulations are re-examined every couple of years to keep pace with changing technology and materials’ (Financial Times 15 June 2017). The government makes a virtue of abolishing regulations in the name of efficiency and profitability.

The attack on standards and local government

Grenfell Tower was completed in 1974 and complied with the space standards set out in the 1961 Parker Morris report. This report said that the quality of social housing needed to be improved to match rising living standards. Space standards became mandatory for all council housing by 1969. The compulsory nature of the standards was ended by the 1980 Local Government, Planning and Land Act, when the Thatcher-led Conservative government sought to reduce the cost of housing and bring down public spending. More flats were squeezed into tower blocks to increase accommodation and population density.

After the Great Fire of London in 1666, the Rebuilding of London Act forbade wooden exteriors for housing in favour of ‘bricks, stone, stucco, slate or riveted tiles’ to halt the spread of fires. The 1850 Scottish Burgh Police Act required that all party walls, external walls and roofs be constructed with ‘incombustible’ materials. In 1984 the Building Act empowered Secretaries of State to amend building regulations in England and Wales. Several Secretaries of State made such amendments. In 2012 former Communities and Local Government Secretary Eric Pickles repealed Sections 20 and 21 of the 1984 Act. Consequently, the exterior of buildings no longer had to be fireproof (see Private Eye 14 July 2017). This was done in the name of the then business secretary, Sajid Javid’s, ‘red tape challenge’, intended to get rid of £10bn worth of ‘unnecessary’ regulations. The coroner’s report into the Lakanal House fire in Southwark, London in 2009, which killed six people, noted that until 1985 it was compulsory to use cladding that was flame resistant for 60 minutes. Afterwards it was discretionary.

From 2010 to 2016, local government spending in Britain was slashed by 37% and is scheduled to be further cut. By 2020, many councils will have lost 60% of their income. Local government housing service budgets, which pay for the shelter of homeless people, special accommodation for people with care needs and inspections of private rental properties to see that they meet basic standards, have been cut by 23% since 2010 (London Review of Books 15 December 2016). The 2005 Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order shifted responsibility for fire safety inspection from fire brigades to local councils, without the accompanying resources. The reduction in funding from central to local governments has made councils more dependent on money they can get from council taxes and business rates. This has encouraged the construction of high-value properties and concessions to businesses as ways in which councils can raise money. Hence the march of new expensive tower blocks across London – and the neglect of council homes; council flats yield less council tax than expensive private apartments.

Kensington and Chelsea council made more money last year from the sale of two council houses in the rich south of the borough, £4.5m, than it spent on the cladding for Grenfell Tower, £3.5m. The proceeds of council house sales cannot be spent on existing or new council housing. The council says it has reserves of £274m, but that money cannot be used on council housing. Council housing is paid for out of housing revenue accounts. These accounts were ring-fenced by the Thatcher government in 1980, preventing councils from using money in them to fund council house building. Neither the Conservative Party nor the Labour Party, in government or out, has opposed this rule since. They are opposed to council house building and support only building for profit.

In 1979, 42% of Britons lived in council homes rented from local authorities. By 2009 this had fallen to under 8%. In 1981, rent for a council property took less than 7% of an average income; in 2015, for a private tenancy the figure was 52% (72% in London), higher than anywhere else in Europe. Across Britain, the average price of a home is about £250,000. Major house building firms make an average profit of £127,000 per home built. Property development, private property ownership and letting have become a most profitable means of investing; council ownership gets in the way.

George Monbiot observed that as Grenfell Tower blazed on 14 June, the government’s Red Tape Initiative, chaired by Sir Oliver Letwin, convened to identify if there were any building rules that could be cut (The Guardian 5 July 2017). The Initiative was set up to use Brexit as an opportunity to cut ‘red tape’. While benefit claimants are systematically bound by red tape to humiliate them and deny them what they are entitled to, the Red Tape Initiative boasts that ‘businesses with good records have had fire safety inspections reduced from six hours to 45 minutes’. In 2014, in the name of cutting red tape, Brandon Lewis, currently Immigration Minister, and previously Housing Minister, rejected calls to force construction companies to fit sprinkler systems on the homes they build, saying that for every rule introduced the government will remove two. Installing sprinklers costs firms money. The government stated, ‘it is the responsibility of the fire industry, rather than the government, to market fire-sprinkler systems effectively’. This is not just the abdication of responsibility; it is the active pursuit of increasing company profits at the expense of health and safety. Grenfell Tower had no sprinklers.

Corporate criminals

The Metropolitan Police say that over 60 companies were involved in Grenfell Tower’s refurbishment in 2015-16. Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO) manages public housing for the council; it hired Rydon as the lead contractor for the refurbishment. Kensington and Chelsea council originally intended to use Leadbitter, but it exceeded the target cost. Rydon offered to do the work for £2.6m less than Leadbitter and got the contract. Before the decision was made KCTMO advised that it needed ‘good costs for Councillor Fielding-Mellen’; Rock Fielding-Mellen was chair of the council housing committee and deputy leader of the council. The choice of cladding to be used on the building was changed at a saving of £293,368. The cladding used was intended to imitate that used on private towers across London and so hide the image of Grenfell as ‘sink estate’ from the neighbourhood.

Arconic, the US firm that produced the cladding panels, knew that the flammable version of its products was being used, even when its own literature said that such panels were not suitable for buildings over 40 feet high. Grenfell is 220 feet tall. More fire resistant cladding made by Arconic costs £2 more per square metre. The cladding used had a polyethelene core. Dave Sibert, fire safety adviser for the Fire Brigades Union, described polyethelene as being ‘like solid petrol’. A forensic architect specialising in assessing the causes of fires said, ‘the UK did not require the core of cladding to be fire resistant. In other countries, including Germany and the US, such panels are banned’. The Metropolitan Police said that the cladding and insulation fitted had failed ‘all safety tests’. Rydon claimed its work, ‘met all required building regulations, as well as fire regulation and health and safety standards’. Will anyone be arrested for the crime? The polyethelene core insulation was supplied by Celotex, owned by Saint-Gobain UK. Saint-Gobain’s technical director is Mark Allen; he sits on the Building Regulations Advisory Committee which advises former managing director of Deutsche Bank and current Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, Sajid Javid.

Rydon promotes itself as a specialist in social housing. When the Labour government was elected in 1997 Rydon was registered as a provider to housing associations, local authorities, NHS Trusts and the education sector. In 2002 Rydon entered the Public Private Partnership market with the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) scheme for the Chalcots Estate in Camden. In 2004 Rydon secured the largest mental health PFI contract in the country, for the Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership NHS Trust. The following year HBOS, now part of the Lloyds Banking Group, put up money for a management buyout of Rydon. Rydon’s chief executive is Robert Bond, who received a salary of £424,000 in 2016 and as a shareholder received an estimated £1.4m in dividend payments. Other shareholders in Rydon include two firms registered in the tax haven of Jersey (see Corporate Watch). One of the firms, Coller Capital, bought a stake in Rydon in 2010 as part of a £332m deal with Lloyds. Its boss, Jeremy Coller, donated £15,000 to the Conservative Party in 2015.

The Metropolitan Police says it is ‘reviewing every company … involved in the building and refurbishment of Grenfell Tower’. Over five weeks on and nobody has been charged. We should demand that all documents relating to Grenfell Tower be opened, all the risk assessments, all the fire service inspection results should be available for community scrutiny. The entire parasitical and destructive capitalist system in Britain and its corrupt ruling class should be indicted and condemned by the working class.

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! 259 August/September 2017