After a winter crisis in which parts of the NHS almost collapsed, the service remains on the ropes. Normally the spring is when some semblance of an adequate service is restored. This will not happen: the chokehold on funding will mean that waiting lists and A&E waiting times will lengthen; the working class will suffer the most. The trade unions will have another national march for the NHS, this time on the 70th anniversary of the NHS’s foundation (30 June), but, as ever, it will be a substitute for real action.

The backdrop to the continuation of the crisis is not just inadequate funding, but a staff shortage made worse by both Brexit and the ‘hostile environment’ for migrants. Added to this is a reduced willingness by staff, nurses in particular, to continue working in impossible conditions. On top of this is the steady increase in the need for NHS services. Figures show the continued pressure and its consequences; for while the number of attendances in April 2018 was 1.5% higher than in April 2017:

- The number of those waiting more than four hours for treatment was 22.7% higher (227,000 in April 2018 compared to 184,000 in April 2017);

- 503,000 patients had to be admitted as an emergency in April 2018, an increase of 6.8% on April 2017;

- 48,000 patients had to wait more than four hours to be admitted following a decision to admit in April 2018, 41% more than in April 2017. 353 patients had to wait more than 12 hours, 148.6% more than in April 2017.

For those waiting for planned operations:

- At the end of March 2018, there were 3.8 million patients on waiting lists, up 5% on the end of April 2017;

- The number of patients waiting more than 18 weeks rose from 363,000 at the end of March 2017 to 491,000 at the end of March 2018;

- Over the same period, the numbers waiting more than 52 weeks rose from 528 to 2,755.

Not enough staff

The staffing crisis, brought on by an eight-year pay freeze and cuts in training budgets, particularly through the removal of nurse training bursaries, is making working conditions impossible. More than three-quarters say that patient care is compromised several times a month because of staff shortages.

Overall, the NHS is short of 42,000 nurses, midwives, physiotherapists and occupational therapists. In the long-term, one in three paramedic posts are vacant across England, as are 15% of nursing posts in London. The proportion of nurses leaving the profession was 8.7% in 2016/17, meaning that nurses are on average working for only 12 years. With the fall in applicants for training, this is unsustainable; 37% of nurses report that they are looking for new jobs. It takes three years to train a nurse, four years for a midwife. Between 2010 and 2016, the number of applications for nurse training courses was between 61,800 and 67,400 per year; in the year after the abolition of bursaries the number fell to just under 55,000. Despite a government pledge in 2015 to increase the number of GPs by 5,000 by 2020, there are now fewer than there were in 2008; 542 left practice in 2017, mainly in poorer areas of the country.

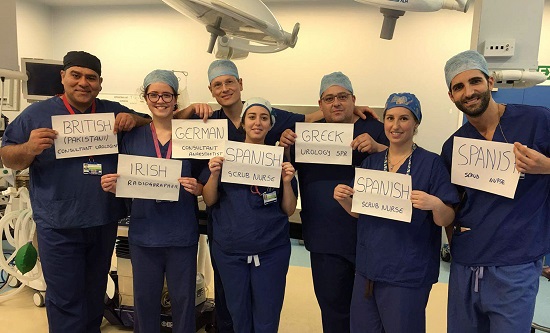

Excluding migrant clinicians

Meanwhile, as part of its ‘hostile environment’ against migrants, the government is refusing to lift the monthly cap on the number of Tier 2 working visas it issues, which means that non-EU doctors are unable to enter the country despite job offers – 100 in Greater Manchester alone, and 18 in one month to work in Nottingham. Brexit will make the situation worse, as it will end agreements about the equivalence of medical qualifications with EU member countries which will be crucial for recruiting EU doctors. As it is, the number of EU nurses leaving the NHS in 2017/18 was 3,962; only 805 joined the nursing register that year, compared to 6,382 the year before.

Fighting back

The Tory government harps on about record levels of funding when they are clearly inadequate. Funding for the NHS must increase in real terms by 4% per year; between 2010 and 2020/21 it will have grown by only 1.2% per annum. Extra money for running costs promised in the 2017 budget was £335m for 2017/18 – immediately swallowed up by hospitals’ plans to meet winter pressures – £1.6bn for the current year and £900m for 2019/20, pitiful sums in the scheme of things. Government raids on NHS capital budgets to the tune of £4.3bn since 2014 to pay for its daily running costs have left the NHS with clapped-out ambulances and antiquated radiology equipment.

The trade union leadership wants demonstrations like the one on 30 June to be the limit on their opposition to the destruction of the NHS. They serve as a diversion from any real challenge to the Tory government. There will be lots of fighting talk, but proposals for concrete action will be few and far between, particularly if they upset the electoral chances of the Labour Party. But over 1.5 million people work in the NHS, most of them in punishing conditions. There is no consideration as to how to mobilise them in a real battle to defend the NHS. This must be on a clear class basis. The impact of austerity and the consequent reliance on foodbanks by the poorest sections of the working class is revealed by recent figures showing that the number of cases of hospital admission for malnutrition has more than tripled since 2008, up to 8,417 from 2,702; while those for scurvy have doubled from 61 to 128. As we have said, what is needed is a movement which unites NHS workers with other sections of the working class who depend on the NHS in a battle which will not capitulate to the threats of the ruling class.

Robert Clough

Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! 264 June/July 2018