FRFI 201 February 2008 / March 2008

‘We have found migrant workers to have a very satisfactory work ethic, in many cases superior to domestic workers.’ – Sainsbury’s, 2007

‘Unemployment has not been rising in the parts of the country where migrant workers have moved to…We reject the fallacy that there is a fixed amount of work to go round… Migrant workers have filled many hard-to-fill vacancies, in some cases vital work in areas of the economy such as education, health, social services, transport in the public sector and in agriculture, construction and hospitality.’ – Trade Union Congress, June 2007

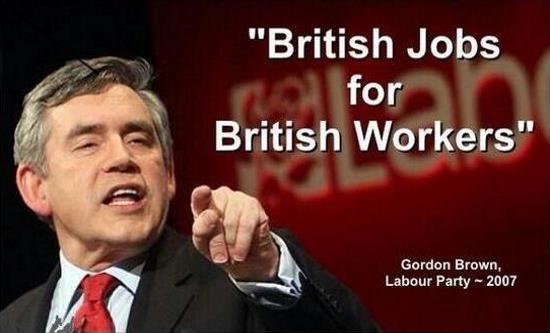

At the September 2007 TUC conference, as the ruling class geared up for a possible autumn election, Labour Prime Minister Gordon Brown courted the racist vote, promising ‘British jobs for British workers’. However, by the end of 2006, foreign-born workers already made up 12.5% of the UK’s working-age population. Migration to Britain has increased significantly in the last five years as the central and east European countries of the ex-socialist bloc joined the European Union (EU). In 2005, there were an estimated 1.5m foreign workers living and working in Britain. Britain has issued 2.5m National Insurance (NI) numbers to migrant workers since 2002. There is now an estimated net annual migration to Britain of 189,000.

Total revenue to Britain from migration has grown from £33.8bn in 1999/2000 to £41.2bn in 2003/04. Migrants now add in the region of £6bn to economic growth annually. An October 2006 analysis by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research in Britain indicated that immigration since 1997 has increased total UK output (GDP) by about 3%. Due to the nature of exploitation of migrant labour, the true figure may be far higher.

The reserve army of labour

Marx described how capitalism relies on the existence of a pool of cheap labour, ‘a mass of human material always ready for exploitation’. This ‘reserve army’ is an ever-ready supply of labour when needed by capitalism, the existence of which keeps wages low for the mass of the working class and maintains workers in a state of uncertainty and instability, knowing they may be hired and fired as needed.

With the development of imperialism, the reserve army ceased to be necessarily located in the same country as the capitalists who use it, and the pool of cheap labour exploited by oppressor nations was increasingly drawn from the countries which had been underdeveloped and oppressed by imperialism.

In Britain in the post-war boom of the 1950s and 1960s, Caribbean and Asian workers from the countries earlier part of the British Empire were encouraged to come to Britain to do low-paid jobs. But even as the government recruited these workers, it was introducing controls and fostering racism to ensure the workforce would remain largely itinerant and not be encouraged to settle in great numbers if no work were available.

In 1979 the Revolutionary Communist Group wrote ‘Racism, Imperialism and the Working Class’,* a detailed study of the situation and treatment of the black and immigrant working class in Britain. We wrote that black immigrant workers formed a specific oppressed layer of the working class and described how racism and imperialism were inextricably linked. Although the details have changed, the fundamentals of this analysis remain true today.

Labour Party’s capitalist immigration policy Britain’s immigration policies today are racist and class-based. Prior to 2000, the Labour government grudgingly welcomed a small number of asylum seekers into Britain, whilst attacking the majority of would-be refugees as selfish, greedy ‘economic migrants’ pretending to flee persecution in order to increase their income or improve their lifestyle. This was then completely turned on its head and now, after seven years of propaganda about ‘managed migration’, we have a tiered immigration policy, organised to meet the needs of capitalism.

At the top of the pecking order are skilled workers and professionals who are encouraged to settle in Britain. They are often headhunted from poorer countries, regardless of the detriment caused to their country of origin by their migration, which is often permanent. Then there are the lower paid workers from EU ‘Accession’ states who are allowed into Britain to seek work but whose welcome is far from assured. In the main they do temporary and insecure jobs at a low wage, keeping British workers’ wages down and increasing profits for capitalism.

At the bottom of the ladder are asylum seekers, who are defamed, detained and deported, and who are officially forbidden from working while their claims are processed. However, as they are either paid only the lowest level of state benefit or provided with no means at all, a sizeable number are forced to work illegally. Their labour, along with that of the undocumented immigrants whose presence here is not officially registered, also contributes to the profits of British capitalism. They are paid the lowest wages and have no access to free health care or other welfare provision.

The British economy

The British economy faces a variety of problems which migrant labour is either helping to solve or mitigate: Wage rises According to the Report on Jobs, a monthly survey of the British labour market, in October 2007 there was a rise in average starting salaries for the 51st consecutive month. The use of cheap migrant labour is helping to keep a lid on these wage increases, thereby maintaining profitability.

Labour shortages and skills shortages Overall there are about 660,000 job vacancies, up from 550,000 in 2004. From 2010 onwards, the number of young people reaching working age will begin to fall by 60,000 every year and 2.1m new workers will be needed by 2020.

There are specific shortages in areas such as construction, engineering, food, agriculture and horticulture, child care, teaching and health. In London, 10,000 skilled construction staff are sought annually and an estimated 45,000 extra people are already needed by the NHS. 150,000 NHS nurses will retire between 2010 and 2016 leading to shortages for some time to come. In 2003, there were 30,000 vacancies for gas installers and a further 10,000 in the water utilities industry. There were over 152,000 sales and customer support vacancies in January 2006.

Skills shortages in professional and associate professional and highly skilled trades (manufacturing, construction, heath and social care and business services) were estimated at 109,000 in 2005. 56% of all skills shortages were in these occupations and affected 4% of all establishments.

Skills gaps

Skills deficiencies in the existing workforce, were said to relate to 1.26m employees in 2005 and affected 16% of businesses (National Employers Skills Survey 2005). Britain is ranked 17th out of 30 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries on low skills and 11th on high skills. Britain and Ireland have two to five times more young people aged 16-35 in the lowest levels of literacy and numeracy than other EU competitors. Even if current targets are met, Britain’s skills base will still be inferior to many other advanced capitalist countries

Although the number of economically active people with no qualifications fell from 45% in 1979 to 12% in 2000, and the proportion with degrees rose from 9% in 1989 to 17% in 2000, Britain is still behind its EU neighbours on skills. The number of apprenticeships in 2006 was 250,000 – the lowest in many years.

In London 50% of companies admit to relying on EU migrant workers and 37% had hired non-EU migrants. Across the UK in a June 2005 survey, 40% of businesses reported using ‘non-UK residents’ to fill posts, and in the public sector this rose to 44%. In a 2001 Employers Skill Survey only 50% of businesses who claimed to experience skills’ shortages indicated a willingness to raise wages.

Professional and skilled migrant workers

The main route of migration from outside the European Economic Area (EEA) in recent years has been through the issuing of Work Permits (WP). 89% of WP approvals are for managerial, technical professional and associate professional occupations. These highly skilled workers, many from south Asia, constitute a professional elite, whose presence in Britain often represents a brain drain in their countries of origin.

WP approvals and extensions have increased dramatically in the last ten years: 139,410 were issued in 2004 – up from 32,704 in 1995. India (33.9%) and the US (10.7%) were the main nationalities in 2005; 26% to the health and medical services and 18% to the computer services sector.

2008 sees the introduction of the single biggest change in migration policy of recent times, a points-based management system to ‘simplify’ the current over 80 different routes of migration from outside the EEA into Britain, such as the Highly Skilled Migrants Programme, Sectors Based Scheme and Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme. The new system will rate all immigrants according to their age, qualifications and skills and experience and direct them to specific sectors of the British economy.

The National Health Service

The NHS is the world’s third biggest employer. Labour’s NHS plan published in 2000 followed a two-year period in which its adherence to Tory spending plans had brought the NHS to near collapse. The main purpose of the plan was to expand NHS capacity to reduce waiting lists (over one million) and waiting times for NHS operations – thousands were waiting more than 18 months and tens of thousands more than a year. From 2002/03, NHS funding in real terms expanded substantially, whilst government targets required a rapid increase in the clinical workforce. The gap between demand and supply from universities and other training establishments had to be met in the short term by immigrant doctors, nursesand professionals allied to medicine. In 2002 nearly half the 10,000 new entrants to the General Medical Council register were from abroad. In 2003 this figure had risen to more than two-thirds of 15,000 registrants. Most of the growth was in doctors from non-European countries. Of the 34,627 additional nurses and midwives recruited in 2003/04, 14,122 (40.8%) came from outside Britain, whilst overall in 2005, 23,000 work permit applications were granted for people in health and medical services. Most were on time-limited contracts. Britain and the EU actively recruited migrant workers from poor countries. South Africa, for example has spent $1bn on training health workers who have since migrated. Thousands of Filipino nurses were recruited, often being reduced to penury by unscrupulous agencies.

As training programmes in Britainstarted to produce qualified staff, competition for clinical posts began to emerge between British-born and immigrant applicants. By August 2007, a quarter of junior doctors who had failed to find posts were home-grown trainees.The government started to turn off the tap: NHS employers were required to show that they could not recruit a resident employee before a work permit was granted to someone from overseas.

Cheap labour from the expanding European Union

While in the post-war years British capitalism relied on a pool of cheap labour from the British Commonwealth (Empire), today it is relying on workers from the former socialist ‘Accession’ countries of the EU. In May 2004 the EU massively expanded its membership, with ten new countries (A10 countries) joining the existing 15. Of these, eight (A8) were former socialist countries in east and central Europe.

In 2007 Romania and Bulgaria (A2 countries) also became members of the EU, bringing the total number of new, and poorer, countries in the enlarged EU to 12 (A12). All these countries had seen a rapid polarisation in wealth since the end of socialism and thousands of trained and unemployed workers now looked to the richer na tions in the west of the EU for employment.

Initially most of the wealthier countries put up barriers to prevent an influx of cheap labour but almost immediately these barriers began to be reversed in the face of a generalised labour shortage across the EU. In nearly all EU countries, populations are expected to fall by about 10% due to declining or stagnant birth rates, and the dependency ratio (ratio of non-working age population to working age population) is expected to double by 2050. This is affecting Germany, Europe’s biggest economy, particularly hard, with 100,000 engineering positions forecast to remain vacant till 2014.

Holland relaxed restrictions in September 2006, directing workers to 16 sectors of the economy, including metallurgy, social services and retail business. France has opened 61 sectors of its economy to thousands of A8 migrant workers. By September 2006 A8 migrants made up 0.6% of the population of Austria (compared to 0.4% in Britain). Under pressure from multinational companies like Siemens and DIHK, even Germany, which supposedly remains closed, has in fact issued permits to half a million A8 workers. Only Britain, Ireland and Sweden did not introduce any form of immediate control to prevent mass migration in search of work from the countries that joined the EU in 2004. The British state made a strategic decision both to recruit cheap labour from the EU and to grab markets in the extended Europe. Unlike the Commonwealth immigrants of the 1950s and 1960s these European immigrants have the additional benefit for the racist state of being white.

Workers Registration Scheme

Following the expansion of the EU in 2004, Britain introduced the Workers Registration Scheme (WRS). It applies only to workers from A8, ex-socialist, countries. Workers from the other two countries which formed the A10 accession states (Cyprus and Malta) have had no restrictions placed on them and do not have to register under the WRS. WRS was introduced specifically to monitor and control A8 employment and reduce access to benefits. A8 workers were each required to register with the Home Office for £50 (now £90) before taking up work. Many A8 workers didn’t register. Self-employed workers who had £20,000 each were exempt. In contrast to the highly skilled migrants from outside the EEA, 82% of the East European workers who come to Britain and seek employment through the WRS occupy low-skilled jobs. WRS workers are a clearly defined reserve army of cheap labour.

An initial promise by the Labour government that A8 workers would have no restrictions placed on their residence in Britain was changed at the last minute to exclude them from out-of work benefits and access to council housing for at least the first 12 months of working in Britain. These restrictions will remain in place at least until April 2009, after which they can be renewed.

About 689,000 A8 workers have entered Britain under WRS since May 2004. In 2005, 61.5% were from Poland where national unemployment is 19% and up to 40% in some areas. About 73% of A8 migrant workers in the construction industry and 61% in the hospitality sector are on self-employed visas according to a 2004 survey.

Migrant workers in Britain from A8 countries are mainly young and single; 82% are aged 18-34 and only 8.4% have dependants. The majority are in good health, and well-educated, with their countries of origin having borne the cost of raising and training them.

713,000 A12 workers registered for NI between 2004/05 and 2006/07; half of A8 workers were short-term migrants and have returned home, but 74,000 remained as long-term migrants in 2005/06 – up from 20,000 in 2003/04. East Europeans still only made up 16% of long-term immigration in 2005/06; while migration from the Indian subcontinent made up 26%.

A8 migrant workers are used predominantly in industries that require unsocial hours and shift-working, such as health, childcare, factory and warehouse work or food processing. The top five sectors of A8 workers, who officially registered with the government between May 2004 and June 2006, were in administration, business and management (ABM), food processing, manufacturing, agriculture and hospitality, making up 79% of the total. The top five occupations were process operatives (37%), warehouse operatives, packers, kitchen and catering staff and domestic staff (cleaners) making up 67% of the total. In reality the numbers working in these labour-intensive, low-paid jobs will be a lot higher. 82% of jobs in the ABM sector are temporary, so they are easier to fill because the migrants are easier to fire. 75% of A8 workers earned £4.50-5.99 per hour in 2004-2006, ie at or below the minimum wage; only 20% of British workers earn below £6 per hour.

While A8 workers must register but are not prevented from seeking work wherever they can, workers from Romania and Bulgaria are generally not permitted to begin work without permission and are only allowed to work in certain sectors. The rules are very complex and many construction workers claiming the status of self-employed workers have been heavily fined for breach ing the rules, unlike their employers.

Capitalism is gangsterism

While many immigrant workers are employed in lower-skilled and lower-paid occupations, sometimes lower than their own skills levels and qualifications demand, thousands are exploited even further. Deception, intimidation, trafficking, withholding of documents and pay, excessive charges for overcrowded accommodation and transport, and working weeks of up to 60 hours are forcing many into a kind of modern day slavery via forced or bonded labour, with businesses, especially agriculture, using immigration status and threat of deportation to maintain control. The government collaborates in this exploitation. In August 2007 it emerged that 40 terrified Bulgarian workers were not paid for 35 days, threatened with deportation if they didn’t pay £100 deposits, and forced to scavenge for food in fields. Their Cornish gangmaster was allowed to continue trading by the government’s Gangmaster Licensing Agency (The Guardian, 14 August 2007).

In 2006 thousands of Eastern European immigrants, including 3,000 in each of London, Dublin and Glasgow, were homeless and destitute.

Racist attacks have increased sharply across Britain in the last two years. Those under attack include Middle Eastern and Asian people targeted as a result of the government’s racist ‘anti-terror’ campaign against Muslims. But central and east European workers are also increasingly targeted. In 2005 it was estimated that there are 49,000 racist attacks a year in Britain.

Hidden migrant labour

Migrants now make up over 12.5% of the British working-age population, as opposed to 8.1% of the population. This does not include the thousands of au pairs who come to Britain every year, who officially are not ‘workers’ but on ‘cultural exchanges’ for a maximum of 24 months. A 2004 survey showed 86% of au pairs were female; 50% worked eight hours a week unpaid ‘overtime’ and most worked two or three jobs. The figures also do not include those registered as ‘self-employed’ or the 157,000 overseas students who came to study in Britain for over a year in 2006 (over 25% of total estimated migration). Foreign students pay double in tuition fees and (in addition to visa fees) are a lucrative source of income for British universities. Foreign students work to make ends meet and so add to the labour force in an unquantifiable way.

Nor does the official figure for migrant workers include the illegal and super-exploited labour of asylum seekers and undocumented immigrants. The government’s much vaunted ‘crackdown on illegal migrant working’ has meant in effect a crackdown on migrants themselves. Between 1998 and 2004, thousands of raids on businesses (1,098 in 2004) resulted in only 17 employers being successfully prosecuted for illegally employing migrants – half those convicted in 2004/05 were fined less than £700, four were fined the maximum £5,000, but thousands of migrants were prosecuted, imprisoned and deported.

Divide and rule

Migrant labour is deliberately used by the British capitalist class to attack the living standards of the working class. However the British working class is not a homogeneous whole, but is split between better-off, privileged workers, on the one hand, and the mass of the working class, including large numbers of low-paid, poor and unemployed workers on the other. The privileged section, the labour aristocracy, actually benefits enormously from immigration as migrant workers help to maintain the profits of British capitalism and keep down the costs of state services.

This is not a new phenomenon. Lenin described the importation of unskilled labour into imperialist countries: ‘The exploitation of worse paid labour from backward countries is particularly characteristic of imperialism, On this exploitation rests, to a certain degree, the parasitism of rich imperialist countries which bribe a part of their workers with higher wages while shamelessly and unrestrainedly exploiting the labour of “cheap” foreign workers.’

The poorest sections of the ‘indigenous’ working class do not benefit in the same way and in time-honoured fashion are encouraged by right-wing politicians and media to blame exploited immigrants for the government’s attacks on their living standards. This has contributed to a rise in racist attacks on immigrants. An ‘indigenous’ working class that opposes immigration is of great benefit to the ruling class. Firstly, it makes it easier to continue to privatise council housing, run down social services and reduce access to health care, if immigrants, rather than the government, are blamed, and secondly whenever there is a downturn in the economy and some of the reserve army is expelled, there is already a vocal body of support for the shift.

The RCG opposes all British immigration controls. It has always been our position that in an imperialist country, immigration restrictions must necessarily be racist. This applies both to claims for asylum and to the ‘management’ of ‘economic migration’.

The answer to the very real problems faced by the poorer sections of the British working class does not lie in attacking immigration but in the fight for decent wages, affordable housing and free health care and education for all, irrespective of nationality or race. Such a struggle is in the interests of the whole working class and oppressed. The labour aristocracy only fights for its own narrow privileges; the rest of the working class must fight for its own rights, side by side with exploited migrant workers against the British capitalist system and the racist, antiworking class Labour government that runs it.

Charles Chinweizu and Nicki Jameson

- Revolutionary Communist 9, June 1979, RCG Publications, ISSN 0306-5626: Available online: www.revolutionary_ communist.org/racism/rcg_rac.html

- Sources include: Salt J, Millar J, Foreign labour in the United Kingdom: current patterns and trends, Office for National Statistics, Labour Market Trends, October 2006. Anderson B, Ruhs M, Rogaly B, Spencer S, Fair enough? Central and East European migrants in low-wage employment in the UK, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2006.